It is one of the largest and most complex reporting projects in recent New York Times history: searching for facts, revelations and answers in the Jeffrey Epstein files.

About two dozen journalists are working through the three million pages, 180,000 images and 2,000 videos contained in the trove of files released about two weeks ago — and so far they’ve seen only 2 to 3 percent of the material. It would take years for a group that size to comb through it all and then verify information as true and publishable, given that so much of it is uncorroborated, in fragments or redacted.

How do we do this work? What are we looking for? In what ways are artificial intelligence tools helpful? What judgment calls have we been making or debating?

I recently held an online discussion about all of this with four of the Times journalists working on the Epstein documents: Kirsten Danis, our Investigations editor; Steve Eder, an investigative reporter; Dylan Freedman, an editor on our A.I. projects team; and Andrew Chavez, an engineer on our Interactive News desk. The discussion has been edited for length and clarity.

Take us back to that moment on Jan. 30 when the Justice Department released the three million pages and thousands of videos and images. What went through your minds?

STEVE EDER: It felt different from the first “Epstein Files” deadline day in mid-December. Then, it felt like a storm was coming because we had no idea what to expect. This time, we were better prepared, with new ways to dig into the documents. I wanted to find out what was there. And it would be a lot.

KIRSTEN DANIS: I was deeply curious, because we almost never get a chance to see the investigative materials underlying any case. Reporters always wish we had subpoena power. In this case, it was like we did.

You suddenly had receipts.

DANIS: Witness statements, emails, bank records. Would this material actually put to rest any of the enduring questions we’ve had about Epstein?

DYLAN FREEDMAN: I dropped all my meetings that day. The scale of this release was hard to visualize: About as tall as the Empire State Building, if you stacked the three million pages, not to mention the multimedia files. My first thought was: How can we create a tool that’s immediately useful to find content in that mammoth trove of information?

ANDREW CHAVEZ: I work a lot with documents. This was a particularly challenging collection. It was unruly: Photos, legal records, text messages, emails. And it was way more than one person could make sense of.

OK. So you knew that this big document release was coming, as Steve said. What did your preparations look like?

DANIS: We had assembled a team of reporters, editors and others who could jump in when the time came. They were colleagues in Washington and on our Investigations, National, Metro and Business desks, and engineers and A.I. journalists. Obviously, you can’t read three million pages. So we decided to start with search terms.

EDER: Trump. Clinton. Gates. Duke of York. My colleagues and I came up with a list of those terms and others about prominent people, places and events that involved Epstein; we’ve added more every day. Some searches were more topical, seeking details on Epstein’s time in jail and death. The plan was to divide those terms and phrases among the reporters and then begin searching the files to see what we found that was new and potentially newsworthy.

CHAVEZ: My desk, Interactive News, maintains a proprietary tool for document reporting, which we knew we’d need for a collection this large. We already had the ability to search millions of pages, but downloading and making millions of pages searchable in a few hours was a new challenge. We had some ideas about how the Justice Department might release the files online, so we built what we could and ran weekly rehearsals against a set of test documents that we assembled.

Did things go like it did in rehearsal, Andrew?

CHAVEZ: There were curveballs. The way they showed up online required us to do a lot of improvising. We never imagined, for example, that they’d release these in a way that you’d have to click through more than 25,000 pages on justice.gov just to find them all. Or that there’d be broken links to sift through, and files constantly disappearing and reappearing.

DANIS: Andrew and his colleagues worked for about 10 hours to get most of the documents uploaded into our tool. We had to rely on the D.O.J.’s clunky search function while that happened.

EDER: But Dylan stepped in to make that all easier.

FREEDMAN: I knew the tool Andrew had worked on would be the ultimate repository of information for reporters, but it would take hours to get all the content indexed. I started thinking about ways to get rougher cuts of information to reporters more quickly, for breaking news.

With the help of A.I., I wrote a tool that leveraged the D.O.J.’s own search functionality to allow reporters to quickly extract every page of search results and put them in a spreadsheet. From there, we populated tabs for search results from key figures linking back to the source material, and reporters crowdsourced verifying the information.

EDER: Dylan’s improv gave us a running start on what would turn into a very long day and night.

Steve, Kirsten, you’ve been working on our Epstein coverage on and off for six years. Once you had these documents, what questions and mysteries did you want to drive at?

EDER: There have been big and basic questions about Epstein. How did he go about doing what he did? How did he get away with so much for so long? Who funded it? One of the big theories out there is that Epstein was collecting the secrets of powerful or wealthy contacts for blackmail or to gain other leverage. This has been hard to pin down over the years — it is an inherently tricky thing to prove or disprove.

DANIS: Another important question was whether there was hard evidence of other criminality. While there are people that investigators described as possible co-conspirators in Epstein’s child sex-trafficking operation, none of those names or information about them was new. We’ve gone through only a tiny fraction of these files, and there’s certainly a lot more to see. But on the question of whether there was a wide pedophilia ring: we’re not seeing proof of that.

What have the documents shed new light on so far?

EDER: While they have not unearthed clear proof of blackmail, at least not from what we’ve seen, they give us a fuller picture of how Epstein interacted with powerful people and how he seemed to see value in claiming to know things about them. It remains a priority to bring as much clarity to this question as we could.

DANIS: We’re getting an inside look at how he operated, always trading gifts and favors for access and power. You can see how he would try to entice elites into his orbit by inviting anyone he could think of to his home, to dinner parties and to his island — and who bit and who said no almost right away.

Kirsten, one judgment call we had to make straightaway was how to describe unverified accusations against President Trump in the files. You ultimately pulled me and other colleagues in to discuss.

DANIS: Almost anything about the president was going to be newsworthy. He had swung so hard against releasing this material that it naturally raised the question of whether he was shielding anything, especially about himself.

We found a document that investigators had pulled together last summer summarizing more than a dozen tips they had received about Trump and Epstein, including sexual abuse. But the tips were unverified and had no dates or names, so we couldn’t report them out ourselves, at least not right away. Anyone can call the F.B.I. and give a tip — there’s no way to know just from the document what’s true or not. We don’t publish anonymous information that we can’t verify ourselves.

So we were debating how we could tell people that these accusations were in there and answer a burning question about this release, but not repeat claims we couldn’t corroborate.

I remember walking into an office in the newsroom and you were there with your laptop, staring hard at our wording about the accusations. We wanted to do two things. First, describe them in general terms, but not in a way that we were airing unverified, salacious details. And second, tell readers why we weren’t doing that. We did that in the near the top of the article:

It is unclear why the investigators assembled the summary, which includes accusations of sexual abuse by Mr. Epstein and Mr. Trump. The emails did not include any corroborating evidence and The New York Times is not describing the details of the unverified claims.

EDER: This is one of the most challenging parts of reporting on these files. Even though these are now public records, it does not mean they are verified, true or accurate. We’ve tried to strike a balance of reporting thoroughly, explaining the existence of these tips and claims, describing what we are seeing, while also not going too far into the realm of unverified or unverifiable accounts. This is something that can be frustrating to readers, who are digging into the files themselves, or seeing such claims posted elsewhere.

DANIS: This would be a good moment to tell people that The Times has a confidential and secure tip line.

FREEDMAN: Viral social media posts narrowed in on details without context. These documents contain duplicates, glitches and inconsistent redactions which can amplify confusion. A prominent example was an email describing a Brazilian woman as “=9yo,” when the “=” was an apparent error, since another version of the document read “19yo.” The tools we built helped us quickly verify these types of claims.

EDER: There are a lot of typos, some probably from Epstein himself and others from software ingesting versions of documents from other software. The bottom line for us was to use caution and look for multiple versions of the same document, when possible.

We reported that these files contained more than 38,000 references to President Trump. Given that number, some readers were surprised that there were not any major new revelations about Trump’s relationship with Epstein. Can you talk more about the president’s presence in these files? Do we see any evidence that the Justice Department removed damaging references to the president, as some have speculated?

EDER: The first thing to know is that while there are a lot of references to President Trump, many of those are in documents that were released by Congress last fall. Epstein often exchanged emails where he or his contacts mentioned Trump; they would also send links to articles mentioning Trump. There are also a lot of news clippings mixed into the files.

DANIS: So many news clippings. Epstein loved to send articles around.

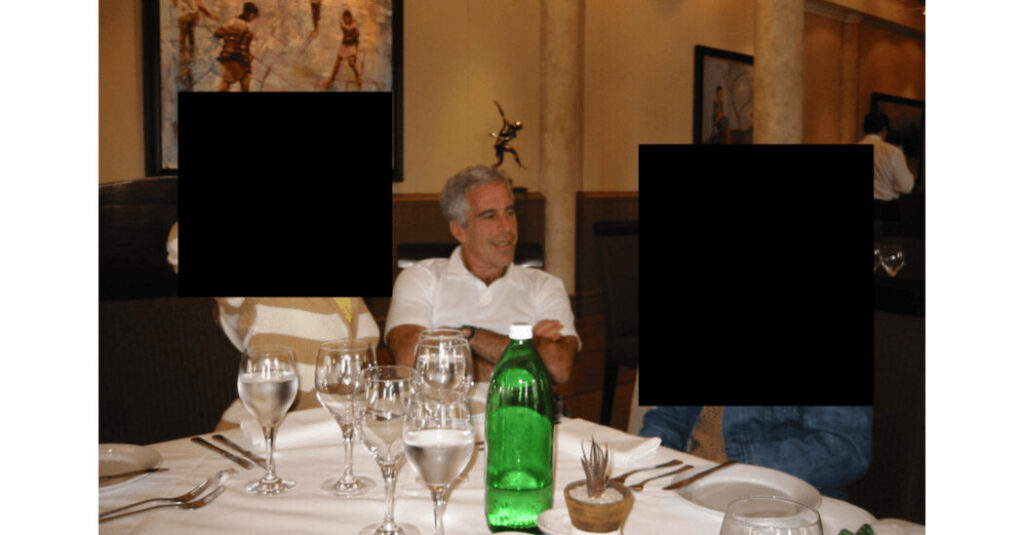

EDER: So the number might look bigger than it seems. But yes, there are references to Trump with redactions too. For example, a file in text message between Epstein and Steve Bannon, a former adviser to Trump, includes a photo of Trump giving a speech — but his face was covered with a black redaction box. That use of redaction has raised a lot of questions about what has been withheld.

Portions of the documents have been redacted by the Justice Department to protect the identities of victims of sexual assault. There are also cases of sloppy redaction, in which sensitive information — including nude photos — were released and later removed. How do you report on documents with redacted pieces, or go about verifying information?

EDER: Yes, as my colleagues reported, the Justice Department published dozens of unredacted nude images as part of the document release. All of this has sowed distrust in the Justice Department’s handling of these files. It’s understandable that there are redactions to protect victims of sexual assault. But in other cases, improper redactions can be an impediment to getting at the truth. If something seems newsworthy, but is redacted, we’ve used other available documents to fill in the blanks and called sources that we’ve developed over years of reporting on Epstein.

CHAVEZ: There’s also been disinformation around redactions, where people are claiming to “undo” redactions using A.I. or other techniques. We built a tool that checked all three million pages for these so-called undo-able redactions and didn’t find any. In many cases, what we’re actually seeing in some online videos is an A.I. hallucination of what it assumes is under the redaction black box.

FREEDMAN: And A.I. is not reliable at guessing what words could fit in a redaction box.

We’ve heard from several readers who argued that The Times needs to cover more of the Epstein files than we already have. Several were adamant that the files prove that Trump is guilty of horrible crimes and that we should focus on that. Steve, do the files prove anything about Trump?

EDER: The files certainly provide ample evidence that Trump and Epstein were close at one time. The files also show that Epstein presented himself as someone who really understood Trump even many years after they fell out in the early 2000s. There are also the tips that Kirsten mentioned earlier, which show how investigators received dozens of leads related to Trump.

DANIS: Trump has a troubling history with women, including being found liable for sexual abuse, and so I understand the instinct on the part of some readers to assume that similar allegations should be treated as if they are likely true. But we work differently. We don’t make assumptions; we need to verify, which often means painstaking work that can take time.

Andrew and Dylan, to assist in the reporting, what A.I.-related tools and other methods did you help build? And what challenges did you grapple with?

CHAVEZ: The first thing we always try to do is make things searchable. But here we also needed ways for reporters to get at the things that weren’t easy targets for search. One way we did that was by leveraging something called “semantic search,” which lets reporters search for concepts and find matching text even if the exact language isn’t in the document. We also built an A.I.-powered tagging and categorization tool to bucket the documents by type and add labels for things that we thought may be useful indicators of newsworthiness.

FREEDMAN: It was hard to anticipate all of the challenges ahead of time. I’m on a team called A.I. Initiatives made up of engineers, designers and editors. As reporters came to us with questions following the release, we were a sort of strike team, rapidly prototyping bespoke software applications to help them.

A.I. enabled us to create specializing tooling to parse the Epstein files in just a couple of days that would normally take engineering teams weeks to build. This included tools to search photos visually, identify duplicate documents, sift through video and audio transcripts and compile research reports on new developments with key figures and topics.

EDER: In November, Congress released a large set of Epstein documents. Then in December, the Justice Department put out the first rounds of the Epstein files. Those releases gave us a chance to stress test our existing tools and create a wish list of search gadgets and buttons.

CHAVEZ: One advantage we have is that teams of software engineers like mine and Dylan’s sit in the newsroom and have the ability to take these kinds of requests. So while reporters are searching the docs at 11 p.m. we are tweaking the search engine and fixing bugs as they find them, making live improvements. And we keep track of reporting lines and try to make sure that the tools we have can get us where we need to go.

FREEDMAN: With A.I., information — text, images, video, audio — is like a liquid; it can be molded into different formats and searched in rich, expressive ways. A.I. will never replace the expert judgment of reporters, but it can make their lives easier and amplify their reporting ambitions.

Dylan, to that end, what is A.I. good at and bad at in a big reporting project like this?

FREEDMAN: A.I. is really good at extracting text from images and audio, captioning photos, assigning structure to text like emails. We can use A.I. to crack open really messy data sets, like this release of documents, that would have previously been impossible to effectively tackle at scale.

A.I. is really bad at news judgment — what information to include, whether it’s important. A.I. can be sloppy and make mistakes that are inexcusable in journalism. It’s super industrious but not super intelligent. A.I. outputs can amplify biases in society. And in my experience, A.I. is not great at producing original ideas (but decent at synthesizing or distilling them).

CHAVEZ: The way we use A.I. is quite different than how most people interface with Gemini and other tools. We are writing software that gives discrete tasks to A.I. that we feel comfortable the technology can handle reliably. For example, we may ask it to let us know if a page has an image or if a document is an email. The stuff we get back may help reporters get to the right material faster, but ultimately a reporter’s eyes on actual documents are what is driving every story.

How do you avoid something like confirmation bias with A.I.?

CHAVEZ: Our reporters treat the signals we surface using A.I. as just another tip. They’re out there talking to sources, reading the source materials and applying decades of experience covering this topic and reading documents like these. So our role — and this is true of any technology we use — becomes more about making sure that everyone understands how we’ve used it and how that affects what they’re seeing from our tools.

FREEDMAN: Confirmation bias is still a very real risk though. A.I. models are so tuned to be helpful, they exhibit a trait called sycophancy in which they will ignore contrary evidence and seek to confirm your suspicions. We can mitigate this by telling people to search for opposing viewpoints. We can also build tools that employ A.I. in less directed ways, for example, to group materials, cluster together themes or surface questions.

A final question: What did you discover in this batch of documents that fundamentally changed the way you think about this story?

EDER: I’ve been on this story for a long time, so there is little that surprises me at this point. But it is still jarring to see Epstein’s communications about women and girls.

DANIS: I agree, Steve. The way that some men talk about women in these documents, reducing them to commodities whose value depends on their hair color or breast size, isn’t at all surprising. But it’s ugly.

EDER: The enormous scope of the story and the reach of Epstein’s collection of contacts still catches me off guard. You would imagine that we’d feel like we know the whole story by now, but not really. It is hard to believe that after all that has been said, there is still much to learn about Epstein and his network.

FREEDMAN: As a relative newcomer to the Epstein beat, I was shocked by the way that Epstein groomed not just women and girls but also powerful men to acquire favor. His network was so much more extensive than I had imagined. It’s the most detailed portrait I’ve seen of an elite class of society operating outside of public scrutiny. Epstein’s disturbing photographs and some of his coded language to describe girls left me with a gaping discomfort.

CHAVEZ: I don’t have the experience with this story that Steve and others do, since I was really just brought in to wrangle the documents. But I’ve seen a lot of document dumps and the material in this one really has the ability to stop you in your tracks. There’s an unfiltered nature, especially in some of the correspondence, that I just found unrecognizable.

Steve Eder has been an investigative reporter for The Times for more than a decade.

The post How The Times Is Digging Into Millions of Pages of Epstein Files appeared first on New York Times.