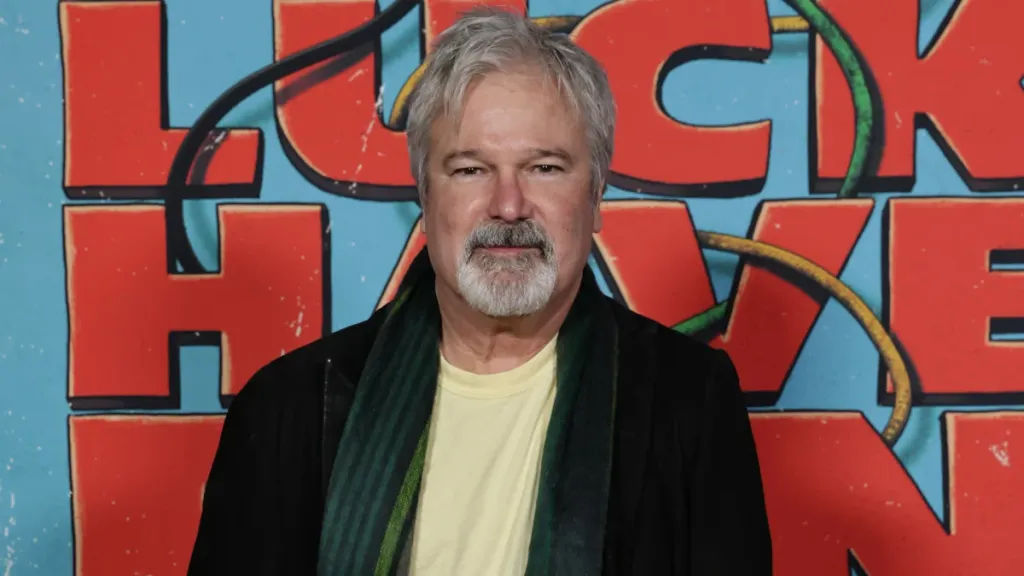

Gore Verbinski has finally returned.

Verbinski is perhaps best known for turning “Pirates of the Caribbean,” a Disney Parks attraction without a discernible storyline or standout characters, into one of the company’s most successful film franchises, with the second film, “Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest” becoming the highest grossing movie that Disney had ever released when it came out in 2006. He’s only made four films since his last “Pirates of the Caribbean” outing – 2007’s beautiful, surreal “Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End” – which seems wrong, somehow.

Remedying that cosmic blunder is indie “Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,” his latest film that arrives in theaters this weekend from boutique label Briarcliff Entertainment, nearly a decade after his previous film was released.

Not that Verbinski has just been sitting around.

“I haven’t gone anywhere. I’ve been here every day checking it out. We’re OK. We’re fighting. We’re fighting today. I think sometimes the stories I want to tell don’t fit the algorithm. But we’re still fighting. We’re still trying,” Verbinski explained.

That need to keep fighting, which is present in “Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die,” is also very much a part of Verbinski’s personality (he got started in punk rock bands and maintains that sensibility). This was well-utilized on this project, considering Verbinski, who has shepherded a multi-billion-dollar film franchise and won an Oscar for Best Animated Feature, had to struggle, fight, beg and plead to make an ambitious sci-fi feature outside of the studio system. For Verbinski, “Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die” was something close to a calling – he was going to figure out how to do it, no matter what. Who cares if it was constantly on the brink of cancellation and severely underfunded?

That’s why he was thrilled that his movie, which follows a group of diner patrons (among them: Haley Lu Richardson, Zazie Beetz, Juno Temple and Michael Peña) who are recruited by a mysterious man from the future (Sam Rockwell) to save humanity from an impending, AI-driven apocalypse, landed with Briarcliff.

“It’s been scrappy because the financials are really tight but I think the team they’ve put together at Briarcliff, they’ve got a fire inside them. It’s not a studio, but I dig that. They’re believers. And I think that fundamentally, we all believe that there’s an audience out there who wants something new. That is what keeps you going, right?” Verbinski said.

From commercials to “Pirates” success

This is a fundamental shift from the movies that Verbinski is used to making.

A graduate of UCLA, Verbinski got a job with an ad agency after college and made a series of memorable commercials for brands like Nike, Coca-Cola and Skittles. After, he directed several commercials for Budweiser that introduced a trio of bullfrogs who would croak, one after the other, Bud.., Weis… and Er. He scooped up Clio Awards and the Cannes Advertising Silver Lion for his efforts and was quickly tapped by a nascent DreamWorks to direct family film “Mouse Hunt.” After flirting with several other projects, including another Disney ride-turned-movie called “Mission to Mars” (eventually directed by Brian De Palma), he would return to DreamWorks for the wacky Brad Pitt/Julia Roberts romantic comedy “The Mexican” and an English-language remake of Japanese horror sensation “The Ring.”

Verbinski reached another stratosphere when he agreed to direct “Pirates of the Caribbean” (eventually saddled with the clunky subtitle “The Curse of the Black Pearl” by Disney chief Michael Eisner).

Initially envisioned as a cheap, direct-to-video adventure movie, “Pirates” gained momentum when super-producer Jerry Bruckheimer agreed to shepherd the project and really caught fire when Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio pitched a supernatural take on the original screenplay – the pirates would be cursed, appearing as skeletons in the moonlight. Bruckheimer reached out to Verbinski, who he had previously tried to woo for “Con Air.” Verbinski loved the cursed pirate idea and was particularly enamored when Johnny Depp expressed interest in playing the lead role of Captain Jack Sparrow. According to James B. Stewart’s indispensable “Disney War,” Verbinski told Depp, “This could be the end of our careers, but let’s have fun.”

Looking back on it now, it’s unfathomable to think that Disney had any doubts about the project, but they did. Eisner balked at the price tag and bemoaned its connection to the attraction. (“The theme park is a drawback,” Eisner reportedly told Bruckheimer, according to Stewart.) They were taken aback by Depp’s look, reportedly negotiating the amount of gold teeth the actor could have, and his performance as the sashaying Jack Sparrow.

According to Stewart, Verbinski quit or came close to quitting the project at least four times, with rumors swirling around the set that he would be fired by Disney. One meeting with Bruckheimer, Verbinski and several Disney executives was described, by Bruckheimer, as the worst meeting he’d ever endured. The film’s budget ballooned and they only had time for a single test screening – in Anaheim, down the street from Disneyland.

“Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl,” released on July 9, 2003, after a splashy premiere at Disneyland, was a sensation. The movie made more than $650 million worldwide and Depp was nominated for a Best Actor Academy Award. Verbinski was cemented as one of Hollywood’s most talented fantasists, a technical virtuoso also keenly tuned into character and emotion.

Quickly, two sequels, shot concurrently, were greenlit, to be released back-to-back in 2006 and 2007. Verbinski, Bruckheimer, Elliott and Rossio returned, with Disney nearly shutting down the movies multiple times. They were also staggering successes, making more than $1 billion and $963 million, respectively. The last film, “At World’s End,” feels like Verbinski’s vision completely unleashed – it opens with a small child getting hung and concludes with a ship-to-ship battle of overwhelming scale and complexity.

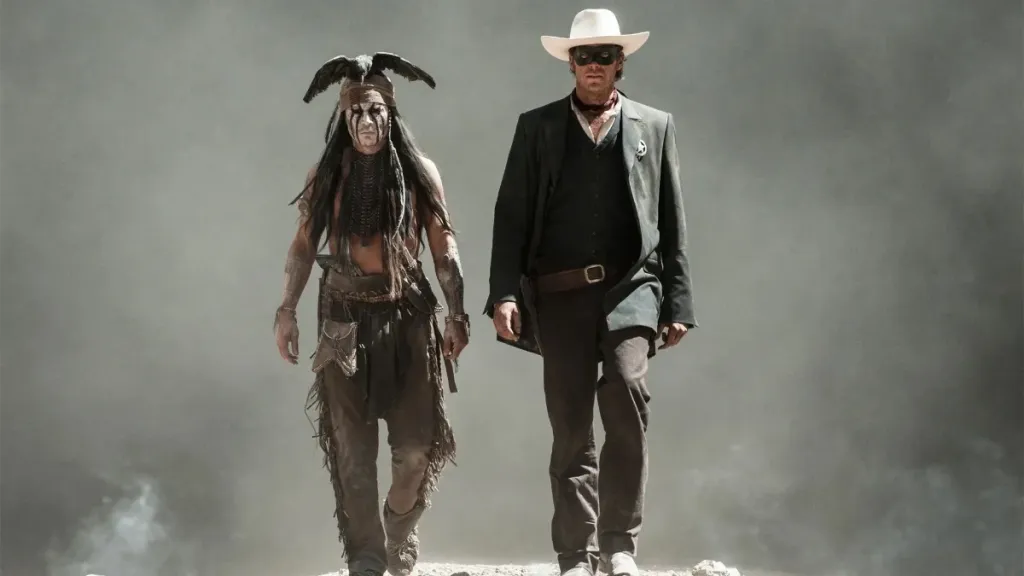

After Verbinski made 2011’s Oscar-winning animated western “Rango,” with Depp as a chameleon with an identity crisis, Verbinski returned to Disney. He re-teamed with Depp and Bruckheimer for “The Lone Ranger,” based on the 1930s radio serial character. It was billed as “Pirates of the Caribbean” on land. But it is a much stranger, more ambitious movie than those earlier films. “I just wanted it to be about trains and about progress and that’s your villain,” Verbinski told me just before the movie was released in 2013.

It was a huge flop, making just $260 million worldwide on a budget of $250 million. Plans for additional films and integrating the characters into the theme parks were quietly canceled. Subsequent “Pirates of the Caribbean” movies have been made, but Verbinski has not returned.

Until “A Cure for Wellness” in 2016, Verbinski had never made a movie outside of the studio system, and while that was an independent production, it benefitted from New Regency’s output deal with 20th Century Fox, which released it (more or less) like a big new movie.

“I’m the same guy tinkering in my basement. Sometimes they blow up and sometimes they don’t and nobody knows why,” Verbinski said. “You have to keep your spirit alive and keep tinkering. And I believe, if you’re not a little mischievous, you’re blind to the absurdity of life. If you have an angle on a narrative, you have a point of view, you’re going to figure out a way to tell that story. I think this one just felt like the why now? I felt like the world was screaming the answer.”

The evolving threat of AI

Verbinski said that the week that he got ahold of the script for “Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die” by writer Matthew Robinson, he felt, “We have got to make this, like, now.”

He got the script in 2020 from producer Erwin Stoff, who was working with Verbinski on an eight-episode miniseries adaptation of Alfred Bester’s 1956 sci-fi novel “The Stars My Destination.” (Verbinski said that he would still like to make it someday.) The script had a date on it — 2017 — so, in Verbinski’s words, “it had been kicking around for a few years and nobody was really interested.”

When he read the script’s opening – an 11-page monologue – Verbinski immediately thought of Rockwell. But he continued to work with Robinson on the screenplay, mostly on the second half of the story, for two years.

“So much has changed from 2017 if you think about AI. We had to change certain ideas and beliefs about what we wanted to say about AI,” Verbinski said.

He wanted to make sure that the AI part was more relevant. Instead of the Skynet-style killing machine imagined in “The Terminator,” Verbinski was intent on conjuring something more tangible and insidious.

“It’s much, much worse; it wants us to like it. It’s going to demand we like it,” Verbinski said. They worked on the backstory for the character eventually played by Rockwell, since in the original drafts it was not really fleshed out. He looked to “Dog Day Afternoon,” where you are always aware of what Al Pacino’s character wants and what he’s willing to do to get it — “The want is so defined and so pure” — as inspiration.

“If you don’t anchor him with real pain and real guilt and a real sense that he’s trying to undo something,” Verbinski said, the movie just wasn’t going to work. Still, the first half of the screenplay, which introduces our characters with brief, episodic flashbacks to their time before entering the diner, remained largely the same.

After Robinson and Verbinski had finished (really finished) the screenplay, they sent it to Rockwell for the role of the man from the future. It’s a high-wire act – manic and hilarious but also tender and tragic, like a spinning top that also makes you feel and believe. Rockwell and Verbinski had wanted to work together since grabbing tacos from a truck in Atwater Village in 2014. The time was, finally, now.

“I just love the guy,” Verbinski said of Rockwell. “I’ve been so lucky. I got to work with Michael Caine, Christopher Walken, Gene Hackman, Johnny Depp. And now I get to say I worked with Sam f–king Rockwell. I am just giddy because I think he’s a national treasure.”

Early financing challenges

Even with an Oscar-winning national treasure like “Sam f–king Rockwell” on board, it was remarkably difficult to raise money for “Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die.”

They first set to fill out their cast, with casting director Denise Champion giving Verbinski some much-needed advice. “She said, ‘Let’s just say we’re making it.’ She put out a casting call and executives who saw that said, ‘What’s the studio?’ And we said, ‘We’re making it,’” Verbinski said. Richardson was soon brought on board, as were Beetz and Peña (who had worked with the director on an as-yet-unreleased animated project). Verbinski had been a PA for Temple’s father, British filmmaker Julian Temple, whom the director describes as his “mentor.”

The cast that Verbinski had assembled was enough to gain the interest of Constantin Film, a German film production company based in Munich that was founded in the early 1950s.

“They were cool with everything, except you have one quarter of the money you’re asking for. We had to will it into existence,” Verbinski said. He estimates that the movie completely shut down “three or four times, just trying to get to a number.” They were approved for the tax incentive and attempted to film in California but couldn’t get to the number Constantin wanted. They tried Vancouver. At one point they were going to go to Winnipeg and shoot in the snow — “It was f–king insane,” Verbinski said, with the film at risk of shutting down for a fourth time.

Finally, the idea was hatched to film in South Africa. “For a f–king movie that takes place on La Cienega Boulevard,” Verbinski said, still sounding slightly miffed. Finally, they agreed. “We’re like, OK, we want to make the movie and we want to make it now.’ Momentum was key,” Verbinski explained.

Once he arrived in South Africa, he was greeted with a crew he had never worked with before, besides his editor, Craig Wood, who has been a close collaborator since Verbinski directed a video in 1995 for the Monster Magnet song “Negasonic Teenage Warhead.”

“It was like, ‘Hi, nice to meet you. I’ve got a machete. We’re going to go through the jungle. We’re gonna tell this psychotic opera,’” Verbinski said. The crews, he said, were great. But there was something more. “I think they all embraced the giddiness of you don’t get to make one like this … The fact that we’re getting to make this movie feels like we’ve uncorked something that was pent up for a long time, or that you’re doing something that they wouldn’t let you do,” Verbinski said.

He is still offered big studio movies, but has yet to commit to anything, besides briefly being attached to a “Gambit” movie for 20th Century Fox. He was attached in 2017 and left in 2018, citing “scheduling conflicts.” He was the third director to leave the film after Rupert Wyatt and Doug Liman.

Another project that Verbinski was attached to was an adaptation of the video game “Bioshock.” But what was interesting to him wasn’t the monsters or the retro-futuristic world, but rather “the Oedipal narrative.” When he briefly mentioned “The Lone Ranger,” he said he was drawn to the project once they hit on the idea of telling it from the Lone Ranger’s Native American sidekick, Tonto’s, point of view.

We wondered if the staunchly anti-AI stance of “Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die” was a turnoff for studios that seem to be courting AI aggressively, with Verbinski’s old partner Disney investing $1 billion in OpenAI and allowing for Sora to utilize its characters.

“I think it’s more that the algorithm is telling them it doesn’t quite fit there. It’s not a sequel, so it doesn’t fit there for a studio. Any studio executive, the first thing you learn is to answer the question, Well, who is it for?” Verbinski said.

“Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die” doesn’t adhere to the rules of any particular genre. It mixes tone wildly and with abandon. It follows five different characters through their own narrative arcs. All of which appealed to Verbinski. “I think a lot of studio data is not necessarily up to speed on an audience’s willingness to go there. They just don’t have the wherewithal to see it. That’s just being risk-averse,” Verbinski said.

The scrappiness of the production extended to post-production. After making several movies with Industrial Light & Magic, the visual effects house that also animated all of Verbinski’s “Rango,” he reached out to a small company called Ghost. “I met their CEO and said, ‘Look you’re not going to make money. This is for the reel.’ Everybody on the movie needs to open a vein. That’s the job. You inspire actors. You have got to inspire the crew. You have to inspire the visual effects people. You’ve got to get everybody you know to maximize their juice because they’re not getting paid,” Verbinski said. “Nobody’s getting paid.”

After the movie was finished, Verbinski was heartened by the response to the movie last year, when it played at Fantastic Fest in Austin, Texas, and Beyond Fest in Los Angeles, known for their rowdy, effusive crowds. Not that it means much in the world of corporate filmmaking. “The pursuit of that isn’t going to guarantee that they’re employed next year,” he said.

Verbinski said that the soundtrack album will get a limited vinyl release and that he’s pushing for a 4K Blu-ray release for home video. “It’s going to be scrappy to the bitter end,” Verbinski said.

As for what’s next, the director doesn’t know.

He said that he still wants to finish “Cattywampus,” an animated musical that Verbinski had worked on at Netflix. The streaming giant dropped the project in the fall of 2022. According to a person with knowledge of the situation, Netflix had spent nearly $100 million on the project, which was being animated by Industrial Light & Magic, and was looking at spending $100 million more to complete it. Instead, they just let the project go.

“We’re trying to one-up ‘Rango,’” said Verbinski.

There’s also “Sandkings,” a short story by George R.R. Martin that originally appeared in a 1979 issue of Omni and was previously adapted as the movie-sized first episode of Showtime’s 1995 revival of “The Outer Limits.” The story follows Simon Kress, a wealthy playboy who becomes enamored with the titular creatures, which set up rudimentary feudal systems and go to war, all within a terrarium in his living room.

“The story is fantastic, but very warped and very dark and funny, with a protagonist that is difficult, I would call him a glorious asshole, like ‘Wolf of Wall Street.’ It’s an interesting challenge, but beautiful, beautiful narrative — feeding your party guests to your creatures,” Verbinski said. “It’s a great unraveling of a character, which I love, and it’s got a lot of what I hope to be high-quality character animation.”

And if those fall through, he can always just direct a big budget studio sequel.

“Yeah, well, come find me and kill me in the balls [if I do that],” Verbinski joked.

We would never.

“Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die” is in theaters on Friday.

The post ‘Everybody on the Movie Needs to Open a Vein’: Inside the Making of Gore Verbinski’s Scrappy ‘Good Luck, Have Fun, Don’t Die’ appeared first on TheWrap.