There was nearly no question Josh Shapiro wouldn’t answer as he traveled the country on his recent book tour, promoting his record as governor of Pennsylvania and flirting with the possibility of an even bigger political future.

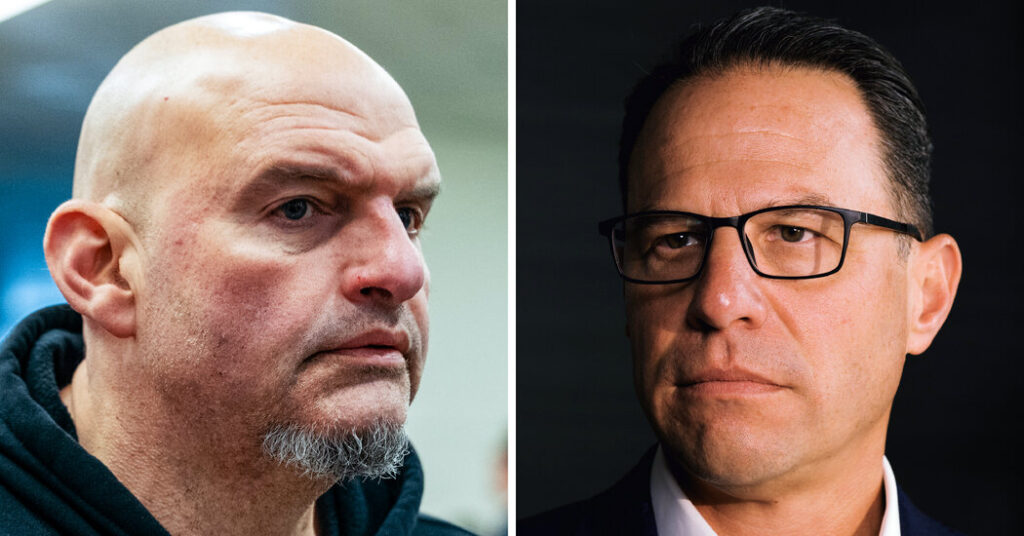

Except one. Would he support the Democratic senator from his state, John Fetterman, for re-election in two years?

“John will decide if he’s going to run for re-election,” Mr. Shapiro told reporters in Washington. “I appreciate his service.”

His terse response offered a glimpse into the strained, and often strange, relationship between the two most powerful Democrats in the country’s biggest battleground state, as both enter pivotal new chapters of their careers.

For years, Mr. Shapiro and Mr. Fetterman climbed their way through the ranks of state politics, rising from local office on opposite sides of the state to become national political stars with egos to match. Both were talked about as potential presidential candidates despite their radically different profiles.

Mr. Shapiro, a buttoned-up, bespectacled state legislator from the Philadelphia suburbs, emerged as a political moderate and a master of the insider’s game. Mr. Fetterman, the towering, tattooed mayor of a struggling old steel town near Pittsburgh, was a lone-wolf politician who disdained the party establishment but excited the liberal grass-roots.

Yet in recent years, their trajectories have sharply diverged: Mr. Shapiro is now one of the country’s most popular governors, widely seen as a possible White House contender in 2028. Mr. Fetterman, relishing clashes with the left, has become a Democratic pariah, and has struggled with mental and physical health challenges.

While private animosity is common between politicians, Mr. Fetterman has propelled their long-fraught relationship to the public eye, broadcasting his resentments toward a sitting governor of his own party in a way that Pennsylvania political veterans say has little modern precedent.

In a memoir published late last year, Mr. Fetterman mentions the governor more than 40 times, devoting an entire chapter, titled “The Shapiro Affair,” to the souring of their relationship. By contrast, Mr. Shapiro name-checks the senator twice in his newly released book.

“Josh and I were very different in style,” Mr. Fetterman wrote in his book, describing himself as “more immediate and sometimes prickly.” He added, “Shapiro, for his part, always had an eye on how the politics would play.”

Aides to both men declined to comment on the relationship. Over the years, Mr. Shapiro and, to some extent, Mr. Fetterman have publicly sought to downplay reports of friction, insisting their offices have a working relationship.

But it’s not clear when they last spoke one on one. They rarely appear at events together.

Allies and former aides to both men describe the tensions as one-sided, with Mr. Fetterman far more focused on Mr. Shapiro. More than one said that the relationship, or lack thereof, reminded them of a famous scene in the television show “Mad Men,” in which someone tells the protagonist, Don Draper, that he feels bad for him.

“I don’t think about you at all,” Draper replies.

Pardon Board Differences

Their story dates to 2008, according to Mr. Fetterman, who wrote that they met while serving as electors for President Barack Obama.

Mr. Fetterman backed Mr. Shapiro’s bid for attorney general in 2016, hosting fund-raisers at his home, he wrote. They saw each other around the state as Mr. Fetterman ran unsuccessfully for Senate in 2016, and later for lieutenant governor.

Mr. Shapiro was “smart and savvy,” Mr. Fetterman wrote in his book. “He is a credit to the state and may one day be a credit to the country. I remember fondly the days when we were nobodies trying to climb the ladder. Even if we no longer speak.”

Things began to deteriorate when they served on Pennsylvania’s Board of Pardons, a five-member panel that is little known in national politics but that played an outsize role in shaping Mr. Fetterman’s animosity toward Mr. Shapiro.

As lieutenant governor, Mr. Fetterman led the board, one of his few duties that by his own account were not “largely ceremonial.” As attorney general, Mr. Shapiro also served on the board.

Mr. Fetterman was a passionate advocate for granting early release to some people serving life sentences, offering emotional speeches arguing for clemency.

He was especially exasperated by Mr. Shapiro’s hesitation to grant a commutation to two brothers who said they were innocent of murder — a reluctance Mr. Fetterman attributed to concerns about “optics.”

In a live-streamed 2020 meeting, Mr. Fetterman grew so angry with Mr. Shapiro that he called him a “fucking asshole” — not realizing, he said, that his microphone was on.

Mr. Fetterman wrote that at one point, he leveled a political threat, saying that he had “all but” told Mr. Shapiro he would challenge him for the Democratic nomination for governor if he did not change his mind. If Mr. Shapiro voted to release the brothers, Mr. Fetterman suggested, he would run for Senate.

Mr. Fetterman then “dropped some breadcrumbs” with The Philadelphia Inquirer, he wrote in his book, tipping off the news media to the conversation to “get something on the record.”

An aide to Mr. Shapiro later denied that the threat had ever been made.

In December 2020, the board unanimously recommended freeing the brothers. Mr. Fetterman appeared speechless when it came time for him to cast his vote.

Mr. Shapiro spoke on his behalf: “I’m a yes, and I think the lieutenant governor is a yes as well.”

In his own memoir, Mr. Shapiro described the pardon board work as an intense process that required balancing public safety considerations, clemency pleas and the views of victims and their families.

“I felt an enormous sense of responsibility with every case I voted on,” he wrote.

In February 2021, Mr. Fetterman announced his campaign for Senate, and Mr. Shapiro began his bid for governor later that year.

But the experience with Mr. Shapiro on the board stuck with Mr. Fetterman, and he wrote that the relationship had never recovered.

Years of Tension

The two men’s fortunes began to diverge in 2022, when Mr. Fetterman suffered a near-fatal stroke in the middle of his Senate campaign.

They both won their elections that fall, each racking up notable margins of victory in red areas. But since then, Mr. Shapiro’s profile has risen while Mr. Fetterman has charted a much rockier path.

Mr. Fetterman has alienated much of his party with his contrarian positions, defending immigration enforcement agents for wearing masks and backing the idea of buying Greenland.

Polling from late last year showed Mr. Fetterman’s approval ratings among Democrats hovering in the 30s. (Mr. Shapiro, by contrast, was in the 90s.)

And while he and Mr. Shapiro are both prominent supporters of Israel, Mr. Fetterman’s mockery of pro-Palestinian protesters angered some Democrats, as did his support of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, of whom Mr. Shapiro is a fierce critic.

He has also faced serious health problems.

In 2023, he was hospitalized for weeks of inpatient treatment for severe depression, and has described experiencing suicidal ideation. In 2024, Mr. Fetterman, who is known for distracted driving and has often taken video calls behind the wheel, was found at fault in a car accident in Maryland that totaled his S.U.V. Last year, a fall after what his team described as “a ventricular fibrillation flare-up” landed him in the hospital again.

Former aides have publicly worried that he was unfit for office, and he has missed a significant number of hearings and votes.

He has attributed his spotty attendance to an unwillingness to waste his time with the chamber’s “throwaway” work. He has said he will not host a town hall because he prefers to be “in a room full of love.” Fellow Democrats say he rarely appears at political or official events in the state.

One Democratic member of the Pennsylvania congressional delegation, who insisted on anonymity to discuss private interactions, said they did not know a single Democratic colleague from the state who had “any sort of relationship with Fetterman whatsoever.”

Mr. Shapiro has declined to comment on Mr. Fetterman’s health or his effectiveness in his position.

“I think the best judge of Senator Fetterman’s health is Senator Fetterman and his family,” he told reporters last year.

Former Fetterman aides say he maintained his presidential aspirations through many of his challenges.

They say that Mr. Fetterman believes Mr. Shapiro used his 2022 victory against a weak Republican as a steppingstone. Mr. Fetterman is frustrated that his Senate victory, in a far more competitive general election, did not draw the same political admiration.

During the 2024 presidential campaign, Mr. Fetterman also thought Mr. Shapiro was not sufficiently loyal to President Joseph R. Biden Jr., according to a former aide. He seemed to view the Democratic backlash against Mr. Biden through the lens of his own experience facing pressure to drop out after his stroke.

When news circulated that Vice President Kamala Harris was considering Mr. Shapiro for vice president, Mr. Fetterman relayed his concerns through aides and the media that the governor was overly ambitious and would be disloyal to any future administration.

After Ms. Harris chose Gov. Tim Walz of Minnesota, Mr. Shapiro delivered an impassioned speech at a Philadelphia rally introducing the ticket. Mr. Fetterman sat stone-faced in the crowd of 12,000 cheering supporters.

In a testy television interview days later, Mr. Fetterman denied instructing anyone on his team to denigrate Mr. Shapiro. Mr. Shapiro offered a brusque response: “I have never played small ball. I am not going to start now,” he told reporters.

Political veterans in Pennsylvania, where ambitious politicians are always trying to one-up one another, struggled to find a parallel to the open tension between such prominent state officials.

“It’s more than a style difference — they have really deep differences about the way politicians should be,” said former Representative Conor Lamb of Pennsylvania, who lost to Mr. Fetterman in the 2022 primary race but may challenge him in 2028. Mr. Shapiro “works hard to convey a sense that he’s been trusted with public office and that he owes the public something.” He added, “ And that’s just something I don’t see from John.”

Lisa Lerer is a national political reporter for The Times, based in New York. She has covered American politics for nearly two decades.

The post Why Pennsylvania’s Two Most Powerful Democrats Don’t Speak appeared first on New York Times.