Countless American downtowns are struggling to find their identity, and their tax base, after the convulsions of the COVID-era remote-work experiment. But only one major city is poised to demolish its seat of government.

That would be Dallas, where leaders say the monumental I. M. Pei–designed City Hall is in such bad shape that the city might be better off tearing it down and relocating the government into vacant office buildings nearby. That could create an enormous plot for the Dallas Mavericks, whose casino-company owners, the Adelson-Dumont family, want to build what Mavs CEO Rick Welts calls a “full-blown entertainment district” around their new basketball arena. One of the team’s owners, Miriam Adelson, has also been lobbying to legalize casino gambling in Texas, raising the possibility that Dallas City Hall might ultimately be razed for a casino—a perfect symbol for our era of civic impoverishment and gambling addiction.

This half-baked vision may be the nation’s worst downtown-revival strategy, and not only because it would destroy the city’s one-of-a-kind Brutalist colossus. The imagined payoff—a brand-new, suburban-style entertainment district—is based on a fundamental misunderstanding of what makes downtowns worthy of their designation in the first place.

No doubt City Hall needs some work. Dallas began deliberations over the building’s fate this past fall, but the discussion was complicated by staff’s varying estimates of the deferred maintenance bill: The high end was $93 million in 2018, so could it really be $595 million today? Could citizens trust estimates from a government that had just been forced to auction off a new building for its permitting department because it was not up to code? City Hall’s defenders were suspicious to see the eye-watering tab arrive right as the Mavs came looking for a place to play.

The special tragedy of City Hall’s fate is that the building was designed, not so long ago, to represent Dallas’s growth and ambition in a different moment of uncertainty. After John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dealey Plaza, Mayor J. Erik Jonsson envisioned a new building as part of reforms to repair Dallas’s reputation as the “city of hate.” After an extensive listening tour, the Chinese American Pei—a novel choice to design a public building in Texas but, notably, the architect of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, in Boston—concluded that Dallas needed something grand enough to match the pride of its citizens, and sturdy enough to represent the public sector across from the corporate skyscrapers nearby. He persuaded the reluctant city council to buy a huge block of land for a public plaza to properly orient the building toward the central business district.

[Kaid Benfield: From concrete desert to oasis: Designing a better Dallas]

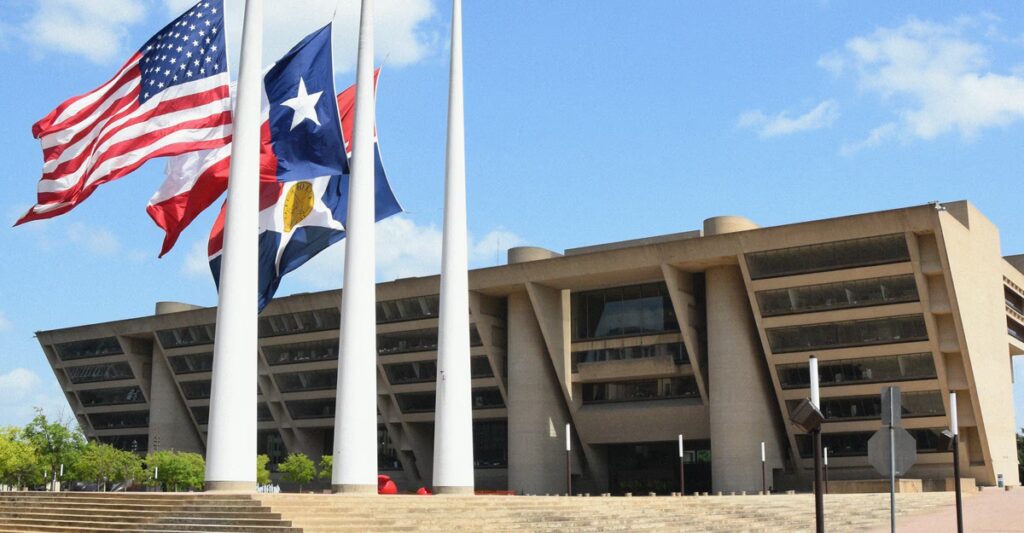

The result, which took more than a decade to finance and construct, is a tremendous concrete anvil with its facade leaning at a vertiginous 34 degrees, 74 feet wider at its roof than at its entrance. Jonsson thought the building was a good reflection of the city. “It’s strong, and the people of Dallas are strong people,” he said. “Concrete is simple, and they are simple people—in the best sense of the word, plain people. So the monolithic structure was entirely appropriate.” But the triangular profile wasn’t just form for form’s sake: Pei hoped that by concentrating the bureaucracy on the upper floors, he would offer arriving citizens a neat and clean experience of government. Mark Lamster, the architecture critic at The Dallas Morning News, has written that no building better exemplifies Dallas: City Hall was “forthright, brash, inventive, optimistic, futuristic and downright beautiful.”

In the years since, not everyone has experienced the building as the city’s welcoming front porch. In his 1990 biography of Pei, Carter Wiseman observed that the building could come across as unfriendly, standoffish, and even ominous: “It seems to frown under the load of municipal responsibility it contains.” The writer Edward McPherson likened it to an “architectural bully, looming overhead, dwarfing the individual and threatening to crush all who dare enter the halls of civic duty.” For Americans of a certain age, the building might be most famous for its role as the evil corporate headquarters in the 1987 film RoboCop. “It has more strength than finesse, Pei himself conceded: “There’s a lot of brute force in this building.” And some people think it’s just plain ugly.

All of which has influenced the public conversation over whether the structure is worth the cost of repairs. Many architects have lined up to save the building, and the designer Steven Holl has written to the mayor that its demolition would be a “crime.” Some locals do not see it that way. “The building has too many limitations and not enough of the assets that make for a functional hub of office work or civic pride,” the developer Shawn Todd wrote in The Dallas Morning News last year. He is part of a chorus of real-estate developers saying that Dallas should tear it down.

Technically, the question of City Hall’s viability is being considered in isolation: What are the costs of fixing the building, and what are the costs of leaving it? But well understood in Dallas is that should the government pack up and go, one developer in particular is on the lookout for a big parcel downtown. A Mavericks-arena district could occupy the vacated land, plus a bunch of empty blocks around it. And the conversation is taking place against a backdrop of more existential questions about the city’s place in the larger, 8.3-million-person region.

On January 5, one of Downtown Dallas’s largest employers, AT&T, announced that it would be moving its headquarters to nearby Plano. That will exacerbate a 27.2 percent office-vacancy rate, one of the highest in the country, according to CoStar data reported by The Wall Street Journal.

One reason for the relocation is particularly concerning for Dallas boosters: By moving more than 20 miles north of downtown, AT&T says it will be closer to most of its workers. It’s common for suburban headquarters to be convenient for a company’s CEO, but the fact that such a location is better for the majority of AT&T’s workforce illustrates how far north the region’s center of gravity has shifted. It’s a mortal threat: What is downtown but the easiest place for the greatest number of people to get to? “To call downtown the center is no longer really true,” Patrick Kennedy, a board member of Dallas Area Rapid Transit, told me. “If you look at the job center based on traffic volume, it’s now some amorphous place up near 635 and the tollway. There’s been so much growth to the north, and so little investment in the south.”

That economic migration is one reason that Plano’s mayor no longer wants to be part of DART, which connects Dallas to Plano by light rail and anchors downtown’s place as the center of the region. Plano is one of five suburbs, with a combined population of 600,000, that will hold a vote this spring on whether to secede. (In its place, the suburban mutineers are proposing some kind of subsidized taxi service.)

[Jonathan Chait: Democrats mess with winning in Texas]

In Texas, the question of mass-transit funding is closely tied to the local hunt for corporations and sports teams. The state limits local sales-tax revenue to 2 percent. Every penny that goes to buses and trains is a penny that cannot be spent nabbing a company from a neighboring city—a strategy that feels newly relevant in Dallas’s peripheral business centers, which are out of cheap land and fenced in by still-younger suburbs.

Irving, a suburban rival northwest of Dallas, will also hold a special election this year to determine whether to sever its transit connections to the city and pocket that tax money for other purposes. Last year, Irving rezoned 1,000 acres of land recently purchased by the Las Vegas Sands Corporation, whose COO, Patrick Dumont, is also in charge of the Mavericks, for a “high-intensity mixed use district” that would permit an arena with more than 15,000 seats. The Mavericks insist that’s what they want to build in Dallas, but the suburban escape hatch gives them leverage.

The Mavs originally set their deadline for March, which happens to be right after the Dallas Economic Development Corporation will publicly present the results of its City Hall assessment.

Dallas is in a tough spot: No one likes to see a team move out. Texas has strict rules on the use of eminent domain for economic development, which limits the city’s power to assemble a complex urban site for the team—unless it’s on city-owned land. But trading City Hall for an arena would be short-sighted, overestimating the power of stadiums as engines of regeneration and underestimating the value of a public asset.

Many stadium-led developments disappoint, and students of those deals say that people who point to sports as the source of revitalization in San Diego or Baltimore, for example, mistake correlation for causation. Stadiums usually require huge amounts of public subsidy, in land or tax breaks. They tend to be islands of activity whose spillover effects end at the parking garage (casinos are even worse). They are good for some businesses (bars) but not so much for others (grocery stores, doctor’s offices). They cannibalize jobs and spending that might have occurred elsewhere in the city, and hang the prior stadium and associated neighborhood out to dry—in the Mavs’ case, the 25-year-old American Airlines Center, which is a mile away.

Stadium megadevelopments that entice the public’s contribution with the promise of neighborhood renewal are under way in cities such as Nashville and Washington, D.C., but there is always a risk that economic conditions change and reality falls short of the plans. Such a scenario wouldn’t be the first time a failure to launch led to another parking lot in Downtown Dallas: City Hall itself was designed to permit an extension in the back; now the site is parking.

The push to abandon City Hall is even more reckless. Tearing down the building would trade today’s cost of repair for the cost of demolition, and tomorrow’s maintenance for rent. It would forfeit a purpose-built structure with grounds for public protest, city-council chambers, soaring interior spaces, and a municipal garage for a few vacant floors of office space that no one else wants. It would sacrifice a symbol of the city at a time when downtown’s sense of identity is wavering, to add one more empty lot to a neighborhood that is full of them. It would destroy an irreplaceable piece of America’s cultural heritage to facilitate a real-estate project that could, by the Mavericks’ own admission, just as soon be plopped down by the side of a highway.

[Richard Parker: Seeing the real Dallas]

For decades, a fatal assumption of American downtowns has been that, to compete, they must offer their best approximation of the big, blank parcels and ample parking of their suburban rivals. It’s an impossible game to win. Dallas might instead try to be different. It’s not hard to imagine a stadium district that enfolds City Hall, embracing the contrast and the uniqueness of the historic building in its midst. The jumble, juxtaposition, and surprise of parcel-by-parcel development can distinguish a downtown even when it has lost its claim as the economic center.

This is already happening in Dallas, where the residential population downtown has increased from a few hundred to more than 15,000 over the past two decades, in part thanks to piecemeal conversions of obsolete office buildings. A trio of Dallas architects has made the case that City Hall and the arena could have a symbiotic relationship in a renewed, resident-anchored downtown that would benefit from being busy at all times of day.

That means planning for something other than drivers from elsewhere, with safer and slower streets, local businesses, and redevelopment incentives for vacant lots. That kind of organic growth is what sets a city up to resist the lure of the suburbs and lowers the stakes of negotiations with giants such as AT&T and the Mavs. Nothing is terribly exciting about investing in shade trees or crosswalks, but at least a crosswalk never traded Luka Dončić.

The post The Eclipse of Dallas appeared first on The Atlantic.