Prime Minister Mark Carney of Canada recently described the world that President Trump is dragging us into with this aphorism: “The strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must.”

The quote comes from Thucydides’ fictionalized account of a negotiation between Athens and the rulers of the island of Melos, in the Peloponnesian War. The Melians, who were no match for the Athenians, wished to remain neutral. They complained that Athens’s demand that they submit to its rule was unjust. The Athenians responded that matters of justice exist only between equals. Between those who are strong and those who are weak there is only force.

The dialogue is famous for its stark portrayal of the dictates of political realism. The world is not guided by ideals and values, it demonstrates. It is brokered only by power.

The Trump administration has adopted this philosophy as its own. In a recent interview with Jake Tapper, Stephen Miller said, “We live in a world in which you can talk all you want about international niceties and everything else, but we live in a world, in the real world, Jake, that is governed by strength, that is governed by force, that is governed by power.”

To sympathetic ears, Mr. Miller sounded refreshingly unsentimental and cleareyed. But the “niceties” he disparaged aren’t just some naïve fantasy. They are the values of Christianity, the faith the Trump administration purports to defend and uphold.

After defeating Melos in a siege, Athens slaughtered the island’s men and enslaved its women and children. Such was the nature of the ancient world, a world that was, to borrow Mr. Miller’s words, devoid of “niceties” and “governed by power.”

In his book “Dominion,” the historian Tom Holland describes how it wasn’t until Christianity came along that Western civilization derived the popular conception that the weak and the vanquished had any inherent moral value at all. Telling an ancient Greek or a pre-Christian Roman that their treatment of slaves was morally wrong would have inspired not argument but bewilderment, as if you had told them they were evil for the way they treated their kitchen utensils. These pagans generally believed that their gods favored the strong and were indifferent to the weak.

Christianity upended these assumptions. Christianity took the Jewish God, who cared for the weak and knew the difference between good and evil, and made his message universal. It taught that all humans are God’s creation. To oppress any person, even a slave, is an offense before him. Even more than that: the weak are closer to God than the rich and the powerful.

This moral instinct is so ubiquitous today that we barely recognize it as Judeo-Christian, or even as religious. Adherents of the world’s other great religions have largely integrated it into their ethical frameworks even if this tenet is not central to their faith. It is the basis for the American Declaration of Independence and the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights. As Mr. Holland noted, even anti-Christian revolutionaries, from the Jacobins to the Communists, owe their secular claims of human equality to Christianity; indeed, they are the most radical expressions of it.

That’s not to pretend that those lofty principles have effectively restrained great powers. Mr. Carney is correct that international law has always been, in part, a lie. International norms haven’t stopped the U.S. military from carrying out atrocities all over the world. Christian morality didn’t prevent medieval kings and the Catholic Church from massacring civilians, persecuting Jews and committing genocides in the New World. The American founders, so proud of their Christian piety, betrayed their religion in the most profound way: many of them owned slaves.

Unlike the pagans of antiquity, however, those rulers had to answer to charges of hypocrisy, which corroded their credibility in a way that the Athenians never had to contend with. Purportedly Christian great powers could do what they wanted to, just as the Athenians declared. But unlike the ancients, they did so at a cost to their political legitimacy.

George W. Bush felt obliged to sell his invasion of Iraq in part on the righteous Christian premise that it would liberate oppressed Iraqis from Saddam Hussein’s tyranny. After the Soviets invaded Afghanistan, the United States cast their mujahedeen adversaries not just as tools for U.S. foreign policy goals but as “freedom fighters.” American leaders, unlike Vikings or Spartans, had to make a moral case for the exercise of our power. It wasn’t enough to simply say that we, as the strong, can do what it is in our interest to do. We had to couch it all, however unconvincingly, in a framework that made it palatable to the Christian conscience. This may not have determined the shape of American foreign and domestic policy, but it was the impossibility of making that case that ultimately contributed to the end of slavery, and of European imperialism and American segregation. The moral framework mattered.

That is the world we are leaving behind. By brazenly jacking Venezuela for its oil and threatening to acquire Greenland against its will, the U.S. is acting as the ancient Greeks, the ancient Persians and the Germanic tribes conducted themselves: brutishly, without shame or apology. And the abdication of Christian values is already shaping the conduct of our government toward its citizens, as in Minneapolis, where immigration agents have killed two protesters. The Trump administration appears unconstrained not only by the limits imposed by the Constitution but by the standards of an average American’s conscience. Federal agents’ treatment of both immigrants and U.S. citizens in Minneapolis is the reflection of a government that has abandoned the moral instinct that it is wrong for the powerful to abuse the weak.

JD Vance never tires of pointing out that America is a philosophically Christian nation, and that Christianity is under attack from his political enemies. Such statements get big applause from the Trump-loving crowds he panders to. But the administration he serves in is doing more than any antifa foot soldier to dismantle that philosophy as the fundamental basis of our government’s political legitimacy. To the people leading this administration, Thucydides’ famous aphorism isn’t just an acknowledgment of reality. It is the image of the world they wish to make.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

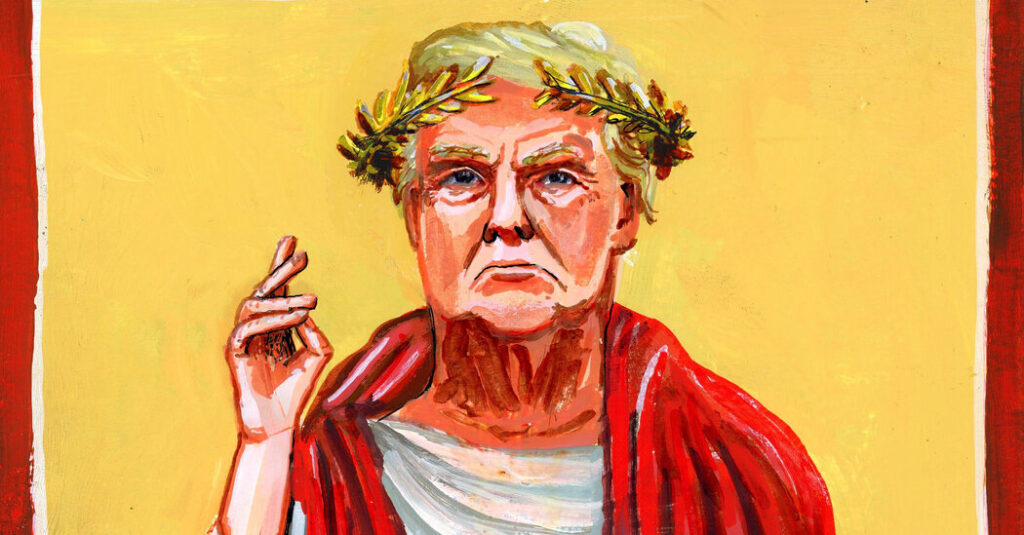

The post Donald Trump, Pagan King appeared first on New York Times.