Los Angeles officials just made it easier to convert empty commercial buildings to housing, opening the door to the creation of thousands of apartments across a city clamoring for housing.

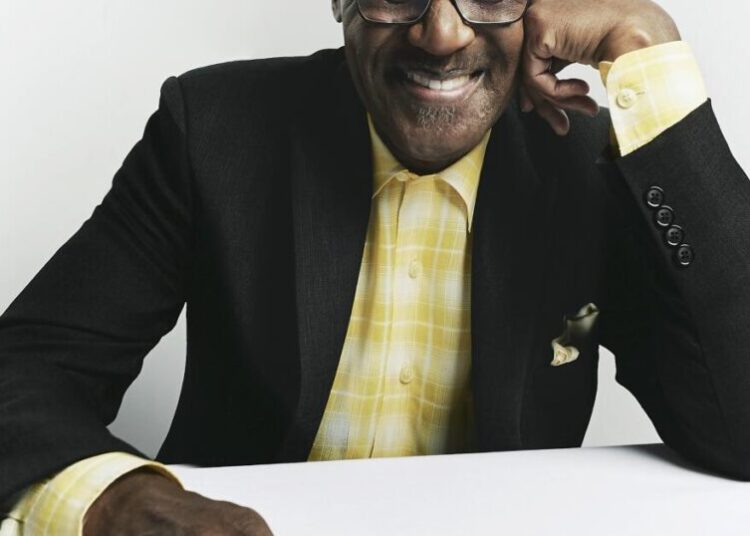

Developer Garrett Lee is already rolling.

After years of struggling to find white-collar tenants for a gleaming office high-rise on the edge of downtown, he has just begun converting its office space into close to 700 apartments.

With the new Citywide Adaptive Reuse Ordinance going into effect this month, many more housing conversions are coming to Los Angeles, Lee said.

“This is monumental for the city.”

The ordinance opens the possibility of conversion for many more buildings than the 1999 guidelines, which paved the way for converting older downtown buildings and jump-started a residential renaissance that turned downtown into a viable neighborhood after decades as a commercial district where few wanted to live.

The first ordinance applied to buildings erected before 1975 and was focused primarily on downtown. Under the new guidelines, commercial buildings that are merely 15 years old throughout Los Angeles can be converted to housing with city staff approval, rather than going through lengthy review processes that may reach the City Council.

Streamlining conversion approvals for projects that meet city guidelines will remove one of the biggest hurdles for developers who have historically had to guess how long it would take to start construction, Lee said.

“When you take that risk off the table, it materially improves the feasibility of conversions,” he said.

“It addresses both the housing shortage and the long-term office vacancy issue,” said Lee, president of Jamison Properties.

There are more than 50 million square feet of empty office space in Los Angeles, according to industry experts, spread among the city’s many commercial districts and corridors such as Wilshire Boulevard.

The new ordinance inspired developer David Tedesco to move ahead with plans to convert a high-profile office building in Sherman Oaks, a neighborhood that wasn’t previously included in the city’s adaptive reuse guidelines.

His company, IMT Residential, plans to turn the former headquarters of Sunkist Growers into 95 apartments.

The eye-catching inverted pyramid designed in brutalist style is visible from the 101 Freeway and served as Sunkist’s headquarters from 1970 to 2013. The Los Angeles Conservancy called the building “a symphony in concrete,” worthy of city landmark status.

Earlier, there were plans to renovate the building for new offices, but as demand for office space plunged after the pandemic, developer Tedesco says his company decided to use the new adaptive reuse ordinance to make it into residences.

The new rules mean “we could move forward a lot faster” and avoid a potentially lengthy environmental impact review, he said.

The 1999 ordinance proved that people wanted to live downtown and that converting old office buildings to housing or hotels could transform a neighborhood, said Ken Bernstein, a principal city planner in L.A.’s Planning Department.

Construction of new apartments followed the wave of conversions downtown in the early 2000s, and the ordinance was expanded to a few other neighborhoods with older buildings, including Hollywood and Koreatown.

But until this month, residential conversions in most of the city still required more approvals, permits and hearings as well as an environmental review, Bernstein said.

“That could be a very time-consuming, cumbersome and expensive process,” he said.

The new rules “unlock the potential,” he said, of thousands of underutilized structures all over the city, including such commercial centers as Westwood, Olympic Boulevard, South Los Angeles, Ventura Boulevard and the Harbor District.

The ordinance is not limited to office buildings. Industrial buildings, stores and even parking garages are eligible for conversion to housing.

Bernstein envisions shopping center owners converting part of their retail and garage space to housing under the new guidelines. Even smaller strip malls would qualify for conversion to housing.

While the new ordinance lowers hurdles for landlords interested in converting their underused buildings, they still face market and regulatory forces that bedevil all housing developers.

Among them are interest rates that make construction loans more expensive . Higher tariffs have driven up the prices of construction materials and equipment, while the crackdown on undocumented workers has thinned and spooked much of the international workforce on which the housing industry depends.

Developers also say that Measure ULA, the city’s “mansion tax” on large property sales, hurts the outlook for the profitability of any housing.

Measure ULA “is really impeding developers from doing any development in the city of Los Angeles,” said local architect Karin Liljegren, who specializes in adaptive reuse projects and helped the city craft the new ordinance.

Developers also worry that new apartments won’t generate enough income to cover construction costs.

Apartment renters accustomed to steady price hikes saw a downward shift last year as the median rent in the L.A. metro area dropped to $2,167 in December — the lowest price in four years, according to data from Apartment List.

Experts disagree on the momentum behind the drop. Some say it’s a sign of things to come, while others suggest it’s merely a brief price plateau and rents will rise again this year.

Conversion activist Nella McOsker, president of the Central City Assn. business advocacy group, said the new ordinance is “tremendous” and creates “incredible flexibility” for owners who want to make changes. But L.A. needs to follow the example of other cities and do more in the way of financial incentives for developers trying to make a project pencil out.

The Central City Assn. wants the city to consider financial incentives for conversions, even though it is experiencing budget shortfalls, McOsker said.

City leaders should consider offering financial incentives, such as those used in other cities, to bridge the gap to profitability, McOsker said, citing programs in other central business districts.

New York, Washington and Boston have property tax abatement programs, for example. San Francisco offers transfer tax exemptions, and Chicago uses tax-increment financing to encourage some redevelopments. In Canada, Calgary offers direct grants.

In Washington and New York, there has been widespread adoption of adaptive reuse, Lee said, resulting in makeovers of buildings that each add 1,000 to 2,000 residential units.

Lee, who has converted nearly 2,000 apartments so far, said he plans to take advantage of terms in the new ordinance that will allow him to put more apartments on each floor.

“We’re taking projects that are fully designed already and we’re redesigning them for more, smaller units,” he said, which helps reduce rents.

The new rolling 15-year age requirement will also bring up a new crop of conversion candidates every year. More recently built structures need fewer upgrades and may not require seismic retrofits to meet safety codes.

“Vintage matters,” Lee said. “Converting a building from 1990 versus one from 2010 is night and day due to the differences in code eras.”

The post Thousands of apartments set to take over empty office buildings with new L.A. ordinance appeared first on Los Angeles Times.