A couple of weeks ago, word began to spread around San Francisco that somebody was organizing a “March for Billionaires.” A mystery organizer had posted on social media that “billionaires get a bad rap,” and soon, some flyers appeared around the city. A website provided a time and rendezvous point; it also celebrated the societal contributions of Jeff Bezos and Taylor Swift, exhorting people to “judge individuals, not classes.” The message seemed to be: Not all billionaires.

Initially, everybody I asked in the city was certain that this was satire, perhaps the workings of Sacha Baron Cohen or a stunt by union activists; after all, the website also lauds the value created by James Dyson, Roger Federer, and the CEO of Chobani (for having “popularized Greek yogurt”). I was reminded of how several years ago, the faux-conspiracists of the Birds Aren’t Real movement rallied outside Twitter’s headquarters to critique dangerous social-media rabbit holes.

Still, in a city where AI founders are giddy about automating entire industries and selling digital “friends,” and in a state that is weighing a new and aggressive tax for its wealthiest residents, I wasn’t so sure. The March for Billionaires website appeared to have thoroughly obscured the ownership of its domain, so I contacted one of the march’s social-media accounts last week and quickly received a response: The organizer would meet me for coffee.

His name is Derik Kauffman, and he seemed very serious. The protest was the first that Kauffman, a 26-year-old AI-start-up founder, had organized. “I’m someone who stands up for what I believe in,” he told me over coffee (well, he ordered a green juice). “Even if that’s unpopular.” For an hour, as I did my best to prod Kauffman’s sincerity, he did not flinch. He is not against social welfare, agreed that poverty is bad, and at one point launched into a detailed discussion of tax loopholes exploited by the ultrarich. Still, although not a billionaire himself, Kauffman is a fanboy. He said that he’d organized the march with both a specific goal—opposing the wealth tax on billionaires in California proposed by a major health-care workers’ union—and a broader one: to spread the word that billionaires are ultimately friends of the working class. His thinking was contradictory at times but extensive; if this was a hoax, the execution was quite good.

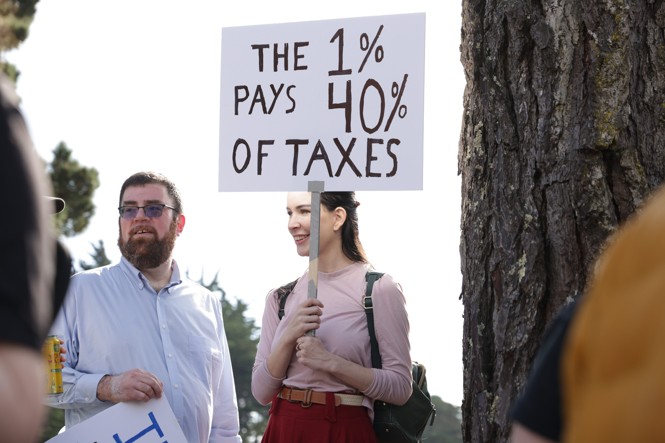

And so, on Saturday, a group of like-minded dissidents gathered with him in Pacific Heights, home to San Francisco’s “Billionaire’s Row,” to lend the nation’s 924 wealthiest people their support. The event topped out, by my count, at 18 pro-billionaire attendees, who hoisted signs with slogans such as Tip Your Landlord and Property Rights Are Human Rights. At least 15 counterprotesters showed up as well, making everything more confusing because they were parodying the idea of supporting billionaires. Some wore full suits or elaborate dresses and held Trillionaires for Trump signs; others offered pulled-pork sandwiches labeled Musk à la Guillotine and chanted “Eat the poor.” Reporters and photographers outnumbered both groups handily.

The proposed “billionaire tax” is a onetime tax on billionaires to make up for federal cuts to California’s health-care budget. Fears about the tax rose after The Wall Street Journal reported that Sergey Brin and Larry Page, the co-founders of Google, were considering leaving the state. The threat of this or any future billionaire tax, Kauffman said, could damage the entrepreneurship that makes California great. (An eclectic set of wealthy and influential figures in the state, including California Governor Gavin Newsom, the White House AI adviser David Sacks, and the venture capitalist Peter Thiel, oppose the initiative.)

Beyond pushing back against any particular policy, the march was also taking a moral stand. “Billionaires are often vilified,” Pablo, one of the demonstrators, told me. “In terms of people appreciating them or just not hating them, they are probably among the worst off in the whole world.” Another, Flo, suggested to me that anti-billionaire sentiment is “growing in left circles” and needs to be resisted. None of the pro-billionaire marchers I spoke with other than Kauffman would tell me their surname.

There is, of course, truth to the statement that billionaires are reviled. A recent Harris Poll survey found that nearly three-quarters of Americans believe that billionaires are too celebrated; more than half believe that billionaires are a threat to democracy. (The march’s timing on the heels of the release of the latest batch of Epstein files, which feature a number of billionaires, is hard to ignore.) As the procession walked toward City Hall, along streets known for upper-end shopping and dining, pedestrians, bikers, drivers, and people seated outside for brunch booed, jeered, and honked; one store owner came out, filmed the march, and called its participants “billionaire brownnosers.” Matt, one of two people holding the large banner at the front of the procession (Billionaires Build Prosperity), told me that he was marching in part because “I try to make a habit of doing one courageous thing a day.”

Perhaps now is a good time for some context: The top 0.1 percent of Americans control 14.4 percent of the nation’s wealth, nearly six times that of the bottom 50 percent. The 400 wealthiest individuals pay a smaller portion of their income in taxes than the average American. The disparity is even more pronounced in Silicon Valley, where nine households control 15 percent of the region’s wealth and the top 0.1 percent control 71 percent of its wealth, according to an analysis from San José State University. The same Harris Poll survey that captured Americans’ hostility toward billionaires also found that 60 percent of respondents wanted to become billionaires themselves.

Trying to have a debate with Kauffman or any of the other pro-billionaire demonstrators—to suggest that immense wealth inequality is harmful and that the market does not, on its own, allow many Americans to get by, let alone thrive—always boiled down to the same, unshakable belief: Billionaires are the engine of the U.S. economy, and because people pay for goods on Amazon and use Google Search, billionaires’ fortunes are deserved. If Amazon causes brick-and-mortar stores to close, it’s simply because those stores “weren’t providing as much” value to consumers, Mike, a protester, told me. Never mind the low wages, acquisition of competitors, price manipulation, and other practices many billionaires use to stay on top.

[Read: Welcome to pricing hell]

For all the spectacle, the tensions between the pro- and faux-billionaires were sharp and reflective of real animosity. As the main procession chanted “Property rights are human rights,” Vincent Gargiulo, a counterprotester dressed in a white mock-billionaire suit, began shouting “Fuck poor people.” Things briefly escalated as a demonstrator confronted Gargiulo for being “not sincere.” He grabbed and snapped her pro-billionaire sign. Then Kauffman approached and threatened to call the police unless Gargiulo left. Another pro-billionaire demonstrator eventually snatched the sign back. “I am offended that there’s a march to support people who are making money that I will never see in my entire life,” Gargiulo told me when I asked why he had broken character. The next chant in defense of the wealthy was “End the class war!”

As the march progressed, something odd began to happen between the countervailing messages. The two sides—representing, I suppose, the 0.01 percent and the rest of us, respectively—almost melded together. Kauffman blared, “Thank you, California billionaires” through his megaphone, and the counterprotesters, wearing crowns, shouted back, “You’re welcome.” As they approached City Hall, where the group would deliver some speeches, the pro-billionaire rally cheered, “Abolish public land” while the counterprotesters jeered, “Tip your landlord,” a slogan that was itself on one of the pro-billionaire posters. At one point, both sides chanted “Poverty should not exist” in unison—the marchers suggesting that billionaires will alleviate poverty, the counterprotesters either trying to reclaim the statement or simply playing into its absurdity.

It was, in a way, a fitting blend. Wealth disparities and unaffordability are among several crises that tech companies are simultaneously contributing to and selling solutions for. (Every pro-billionaire attendee I spoke with described themselves as in tech or “tech adjacent” fields.) Silicon Valley is dizzyingly self-contradictory. Top CEOs have aligned themselves with a xenophobic White House while relying heavily on an immigrant workforce. AI companies offer products that claim to improve the economy by automating large swaths of it. Billboards around San Francisco advertise a product that conducts audits before your AI girlfriend breaks up with you; founders are earnest about curing death. Meanwhile, Elon Musk and other tech leaders post like teenage boys while making society-altering decisions. Everything is ironic, and nothing is.

As the march neared its destination, we passed by an Amazon delivery driver standing outside his van. He was filming the procession, and I approached to ask what he thought of it all. His English was limited, and he seemed a bit confused by what was going on at first, saying that he supported the march—as in, protesting in general. I explained that the march was in support of the likes of Bezos and Musk. Did he support billionaires? “No, no,” he clarified. “Everybody has to get more money. Everybody, not only one person.”

The post The March for Billionaires Was a Funeral for Irony appeared first on The Atlantic.