Steven Spielberg likes to tell a story that captures the tension between art and commerce in 1970s Hollywood: In January 1973, the young filmmaker George Lucas screened a preview of American Graffiti, his movie about hot rods and ’60s kids. Among the hundreds of raucous fans filling San Francisco’s Northpoint Theatre was the Universal Pictures executive Ned Tanen, who was there to review changes requested by the studio. The audience loved what they saw, but Tanen hated it. “This film is a disaster,” he told Lucas in the theater. “I’m so disappointed in you, George.” Francis Ford Coppola, Lucas’s friend and the film’s producer, exploded at Tanen, telling him he should get down on his knees to thank Lucas. Dramatically reaching into his pocket for his checkbook, Coppola offered to buy out the movie rights then and there.

The anecdote—which Paul Fischer recounts in his excellent new book, The Last Kings of Hollywood—encapsulates the complex relationship between Coppola, Lucas, and Spielberg. There was Coppola’s over-the-top defense of his friend with a grandiloquent gesture (Tanen declined to sell). There was Lucas’s prickly resistance to notes of any kind, which would become his hallmark as he worked to upend the studio system. Spielberg, meanwhile, wasn’t even there; safely above the fray, he could enjoy telling the story without worrying about stray fire. Unlike his restless friends, he would learn to work inside Hollywood rather than seeking to destroy it.

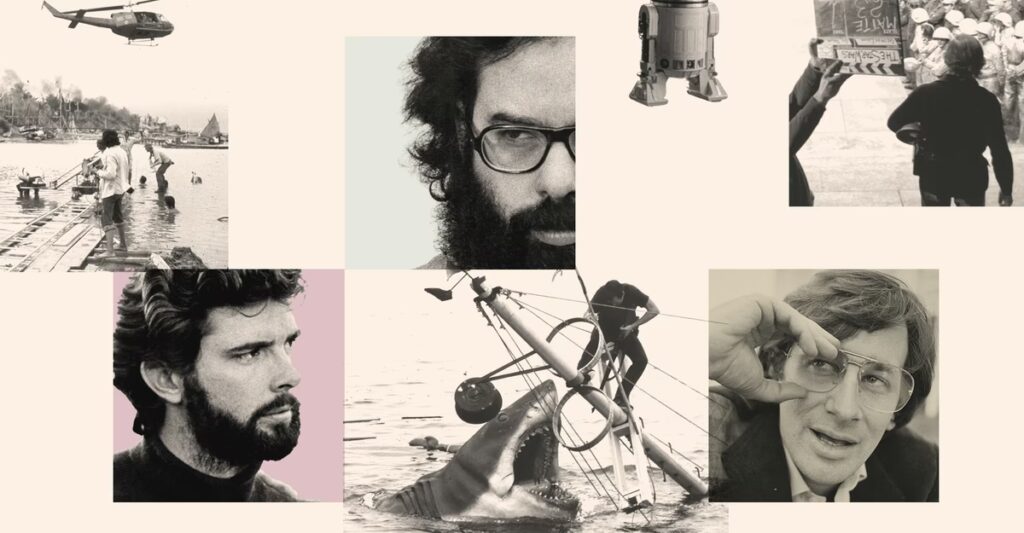

The ’70s were fulcrum years that saw the rise of both the auteur filmmaker and the big blockbuster—sometimes in the same combustible package. At one point in 1976, Coppola was shooting Apocalypse Now while Lucas was filming Star Wars and Spielberg was making Close Encounters of the Third Kind—a remarkable Venn diagram of artistic daring and commercial possibility. Lucas and Spielberg exchanged profit points on their two movies, literally investing in each other’s success. Their peers in the “New Hollywood,” as the era that followed the collapse of the studio system came to be called, were busy creating edgier fare: That same year, Martin Scorsese finished Taxi Driver and Brian De Palma released Carrie. Yet as Fischer shows in The Last Kings of Hollywood, Coppola, Lucas, and Spielberg are worth isolating and studying as a trio. In doing so, he derives a fresh idea from a period that has already been exhaustively studied in books and documentary films. Instead of lauding the triumph of the solo artist or eulogizing the uniqueness of a bygone time, Fischer demonstrates the evergreen value of collaboration.

The three directors—members of a boys’ club in an era rife with them—embodied not just creative drive and box-office magic but also an artistically productive camaraderie. They critiqued one another’s work, inspired their peers to do better, fought bitterly, made up easily, and provided mutual support—both financial and moral. And they set an inspiring example for today’s filmmakers. Hollywood is currently flirting with a return to the studio era, a time when directors were not powerful artists but hired hands: brought on by studios and producers to make sure the actors hit their marks and the productions stayed on schedule. Think of the roster of directors who have shuttled through to handle individual films in the Marvel, Mission Impossible, Harry Potter, and James Bond franchises—not to mention the long list of jobbing TV directors in the age of the big-name showrunner. Fischer provides a counternarrative from a parallel universe: If studios won’t push directors to make great original films, perhaps competition and encouragement from their peers will.

Some of the best filmmakers working today already know this. The “Three Amigos” of Mexican cinema—Alfonso Cuarón, Guillermo del Toro, and Alejandro G. Iñárritu—have been friends for decades, trading brutally honest notes and collaborating on blocking and editing. When Paul Thomas Anderson interviewed Quentin Tarantino in 2019 for a Director’s Guild podcast, Anderson’s admiration for his friend’s movie was palpable. In turn, Tarantino has described Anderson as a “very friendly” combatant, noting, “If I reach high points with Inglourious Basterds, it is partly because Paul came out with There Will Be Blood a couple years ago, and I realized I had to bring up my game.” Yet such relationships are about more than exchanging praise. Tarantino’s recent criticism of Paul Dano’s acting in There Will Be Blood was perhaps ungentlemanly, but it also served as constructive criticism: Casting matters.

[Read: A movie that touches one wrong nerve after another]

This sort of friendly rivalry is especially vital today. Warner Brothers waits to be subsumed by Netflix or Paramount, cinemas are losing customers to streaming, and franchise entertainment continues to dumb us all down. There isn’t much of a structural or commercial imperative to tell bold, original stories. Yet an artistic imperative still feels promising: one-upping your brilliant friends. Such creative competition transcends media and dates back generations. Herman Melville dedicated Moby-Dick to Nathaniel Hawthorne “in token of my admiration for his genius.” Paul McCartney and John Lennon heard the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds and were inspired to write Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. And Spielberg watched The Godfather and feared he would never make anything as good—before going on to become the most celebrated American filmmaker of his generation.

In describing his central trio’s rise to prominence in the 1970s, Fischer positions Coppola as Lucas’s big-brother figure, and Lucas as Spielberg’s. Partly this tracks with their ages, but it has as much to do with their personalities. Coppola, the head-of-table colossus, was fearless and senseless, a beautiful wreck, as lax with details as he was committed to art. Lucas, in his neat beard and plaid shirts, was shy but certain in his own beliefs, favoring big ideas over execution. Spielberg—youthful, awkward, affable, scarred—was a protean talent who found gold dust in every shot. Coppola gave Lucas his first job, as Coppola’s assistant in the late ’60s. Later, the pair accepted a cold call from Spielberg, who asked if he could come by and talk shop. He was intimidated by Lucas, but Lucas was in awe of Spielberg, who at 22 already had several TV-directing credits.

Much of The Last Kings of Hollywood is devoted to the three near-fiascos that these filmmakers turned into generational hits in the mid-1970s. The shoots for Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, Spielberg’s Jaws, and Lucas’s Star Wars were famously chaotic. Apocalypse stretched on for months in the Philippine jungle, the shark in Jaws didn’t work, and Lucas’s crew couldn’t stand him. The trio busted budgets as well as deadlines but made enduring movies. Fischer skillfully braids the three stories together, situating them in an atmosphere of creative ferment and reckless churn. Each director responded to success in his own way. Coppola and Lucas used their leverage to get out of Hollywood, heading to Northern California to focus on their companies, American Zoetrope and Lucasfilm, respectively. Spielberg stayed put, accepting the constraints of the major studios without diluting his artistic ambitions.

The rifts among these friends—particularly between Lucas and Coppola—could be severe. After American Graffiti became a hit, Lucas proved reluctant to share profits he had contractually agreed on with Lucas. Afterward, the pair fought over projects. Apocalypse Now was originally supposed to be Lucas’s to direct, yet Coppola needed to work after The Godfather: Part II, preferably with an original screenplay rather than another book adaptation. Coppola owned John Milius’s script for Apocalypse, and he told Lucas he might just direct it himself—and “was oblivious to the pain it caused when he took over,” Fischer writes. But there was also collaboration. Although Indiana Jones was Lucas’s idea, Spielberg directed the first four installments of the franchise. The two spitballed the first movie, Raiders of the Lost Ark, while vacationing in Hawaii in 1977. When Paramount tried to condition the deal on finding a different director, “George replied that he was committed to Steven.”

The Last Kings of Hollywood contains few scoops, but the book does offer fresh perspective, particularly with respect to Lucas. Fischer unearthed the contracts for The Empire Strikes Back in the producer Gary Kurtz’s papers, finding that Lucas demanded an astonishing 52.5 percent of the movie’s profits up to $20 million, 72.5 percent up to $100 million, and 77.5 percent above that—in perpetuity. Lucas’s focus on getting paid brings him in for the book’s harshest criticism; Fischer casts him as a rebel turned sellout. “Once a young director who valued a film’s quality and integrity above all,” Fischer writes, “he had slipped into the thinking that he and Francis deplored in film executives.” He made Return of the Jedi as a money play in order to grow his empire, Fischer alleges. “The bottom line had become as much a concern to him as the quality of the film on the screen.” Yet Lucas was trying to break free of Hollywood, and building new infrastructure was expensive. Money meant creative freedom.

[Read: How Disney mismanaged the Star Wars universe]

Art, like money, occasionally trumped friendship—but sometimes for the better. Coppola’s decision to muscle in on Apocalypse Now almost certainly led to a superior movie. It is hard to imagine a Lucas-directed version: special effects rather than practical ones, wooden dialogue, and lower stakes. Coppola pushed the film into famously gonzo territory, and the film shoot nearly killed him—not to mention his leading man, Martin Sheen. Despite or because of this, the director managed to capture the hallucinatory madness and violent futility of the Vietnam War.

Directors in the ’70s could be harsh in their feedback. When Lucas screened an early cut of Star Wars for a group of filmmakers, Spielberg was supportive, but Brian De Palma gave astringent and ultimately priceless counsel. Feeling lost in the space opera, he suggested an opening text crawl, as in the old Flash Gordon movies, to orient the audience. “The trouble with the Hollywood system is you’re not getting correct feedback,” De Palma told Fischer. “What was good about our group was, we were very honest with each other.” Lucas took the suggestion, and the now-legendary opening to the movie (“A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away”) both situated and transported viewers.

Why did Lucas take the note from De Palma while thumbing his nose at studio suggestions? Because fellow directors usually aim to make movies better, not just more salable. This year, the director Chloé Zhao shared a comment that her close friend Ryan Coogler, the Sinners filmmaker, provided after seeing her latest movie, Hamnet. Coogler told Zhao that it was her first project in which she truly revealed herself. “The other films were beautiful but you hid behind things,” he said. “This is the first time I saw you in there.” It was a lovely compliment, but also an implicit challenge: You’ve taken a step forward. Keep pushing. Coogler was not merely providing input; he was also acknowledging inspiration. An extraordinary film by a peer and competitor had touched him, and perhaps it will elevate his next project.

Fischer’s title—The Last Kings of Hollywood—suggests a long-lost era, nodding to a moment when a handful of directors with visions as big as their egos were allowed to take huge swings. This is probably mostly right—studios’ appetite for risk keeps shrinking, sequels and reboots are favored over original films, and the days of out-of-control productions dancing on the knife-edge of catastrophe may well be behind us. But in recent movies such as Sinners and Anderson’s One Battle After Another, there is evidence that something in the antics of Coppola, Lucas, and Spielberg survives. Perhaps the artistic fraternity of the ’70s is not a relic, but a model.

Illustration Sources: Screen Archives / Getty; AFP / Getty; Everett Collection: Dirck Halstead / Getty; Graham Morris / Evening Standard / Getty.

The post The Real Secret to a Filmmaker’s Success appeared first on The Atlantic.