President Donald Trump has made housing affordability a centerpiece of his economic agenda, repeatedly emphasizing his desire to see mortgage rates fall.

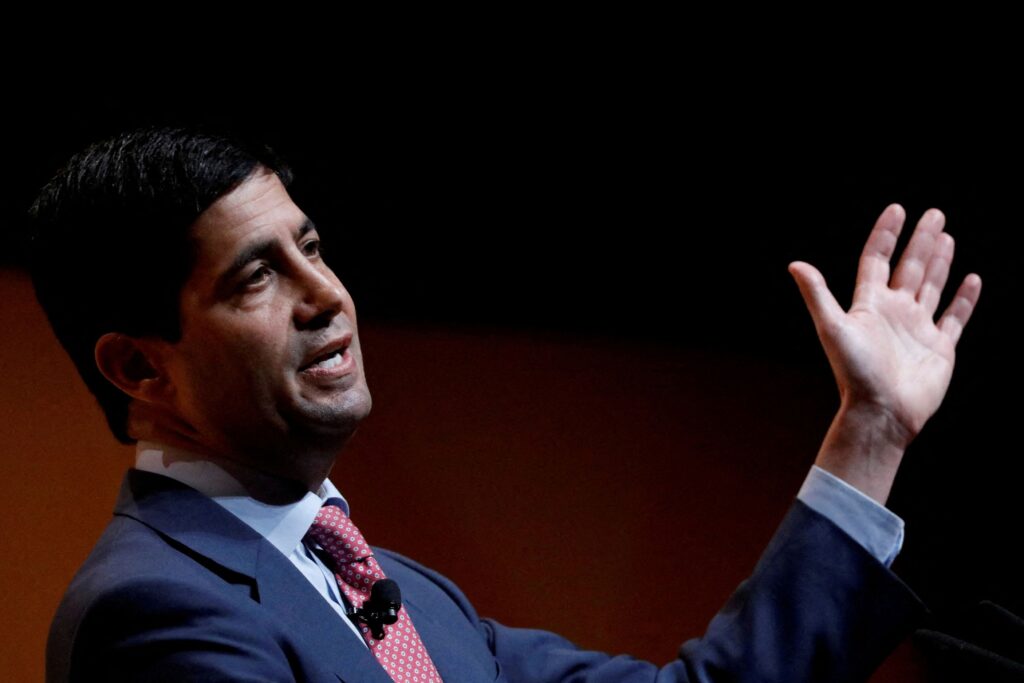

But Trump’s choice to lead the Federal Reserve, Kevin Warsh, has spent years criticizing the central bank’s enormous bond portfolio. Any push to significantly shrink the Fed’s $6.6 trillion balance sheet of Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities could push mortgage rates higher, working against the president’s goals.

The tension between those two goals highlights a potential clash between Trump’s political priorities and the policies embraced by Warsh, who has sharply criticized the Fed’s balance sheet as bloated and distortionary — a shorthand for his view that a giant central-bank portfolio holds long-term interest rates below their natural level and inflates asset prices.

Warsh must still be confirmed by the Senate, but Trump intends for him to start leading the central bank in mid-May, when Jerome H. Powell’s term as Fed chief expires.

“If all he does is move to a smaller Fed balance sheet, it’s hard to see how that would be consistent with lower mortgage rates, and that creates some tension with the president,” said Bill English, a Yale professor and former director of the Fed’s division of monetary affairs.

The Fed influences borrowing costs by adjusting its short-term benchmark interest rate, a lever that ripples through the finance sector and helps shape what consumers pay for car loans, mortgages and other loans.

Policymakers have also relied on a second, less conventional tool: the Fed’s balance sheet. By buying trillions of dollars in longer-term securities, the central bank sought to push down longer-term interest rates. Those purchases make borrowing cheaper because they push Treasury yields lower, which, in turn, influence rates across the economy.

The potential conflict comes as Trump faces political pressure to deliver on promises about housing costs. Mortgage rates, which briefly topped 7 percent in early 2025, have become a flash point for home buyers locked out of the market. Trump has pledged to bring these down, though he has offered few specifics.

“We can drop interest rates to a level, and that’s one thing we do want to do,” he said last month. “That’s natural. That’s good for everybody. You know, the dropping of the interest rate, we should be paying a much lower interest than we are.”

Warsh, a former Wall Street banker and Fed governor, has been a vocal critic of “quantitative easing,” programs designed to rein in longer-term interest rates by ballooning the Fed’s balance sheet during and after the financial crisis. Between 2008 and 2022, the Fed’s assets jumped from about $900 billion to roughly $9 trillion, before shrinking to $6.6 trillion as of last week.

In speeches and writings, Warsh has characterized the massive bond portfolio as an unwelcome legacy of crisis-era policies that should be unwound. Warsh says the Fed’s bond buying encouraged large federal deficits and, ultimately, fueled inflation.

“Each time the Fed jumps into action, the more it expands its size and scope, encroaching further on other macroeconomic domains,” he said in a speech in April. “More debt is accumulated … more capital is misallocated … more institutional lines are crossed … risks of future shocks are magnified … and the Fed is compelled to act even more aggressively the next time.”

The Fed holds about $4.3 trillion in Treasury securities and about $2 trillion in mortgage-backed securities — remnants of the extraordinary measures taken to support the economy during the recession in 2008 and the pandemic in 2020. The bulk of the securities are long-term instruments.

The tension is rooted in basic economics: When the Fed buys large quantities of bonds, it pushes up bond prices and drives down their yields, which translates to lower borrowing costs across the economy. Reversing that process — selling bonds or simply letting them mature without replacement — would probably have the opposite effect, allowing rates to rise as private investors demand higher yields to absorb the supply that might otherwise be purchased by the Fed.

To be sure, many factors influence mortgage rates beyond the Fed’s balance sheet. The central bank’s short-term interest rate policy, inflation expectations, global economic conditions and the health of the housing market all play roles. And it remains unclear exactly what Warsh would do if confirmed as Fed chair — he has not laid out a detailed plan for balance sheet reductions, and his views could evolve once in office.

Warsh and the White House didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Some economists say the tension may be overstated. The underlying balance sheet issues are so complex and thorny, they say, Warsh may have no choice but to kick the can on addressing them.

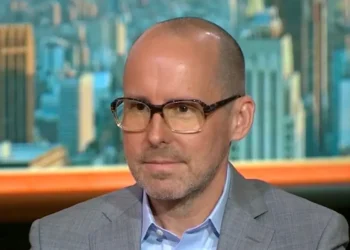

“I suspect Warsh’s desire to reduce the balance sheet will collide with reality and he’ll end up reducing it very gradually, perhaps excusing himself by arguing that the problem is so big it cannot be solved overnight,” said Jason Furman, a former Obama administration economist now at Harvard University.

Though Warsh got the nod in part because the president expects him to cut the Fed’s short-term rate, that doesn’t mean market-driven long-term rates will fall. The Fed has shaved 1.75 points off short-term rates over the past 18 months, yet mortgage rates are roughly the same as in September 2024.

“Almost everywhere you look, Warsh is kind of hamstrung, including on the balance sheet,” said Jon Hilsenrath, a visiting scholar at Duke University’s economics department who focuses on central bank issues.

The post Trump wants lower mortgage rates. His Fed pick may push the other way. appeared first on Washington Post.