Two decades ago, Shih-Pao Lin began collecting MetroCards, the pocket-size blue-and-yellow transit passes used on New York City’s subways and buses, because they were bright, pliable and bountiful.

He was among a small band of artists who for years had found inspiration, steady pay or a measure of fame by crafting sculptures, collages and mosaics out of the floppy cards.

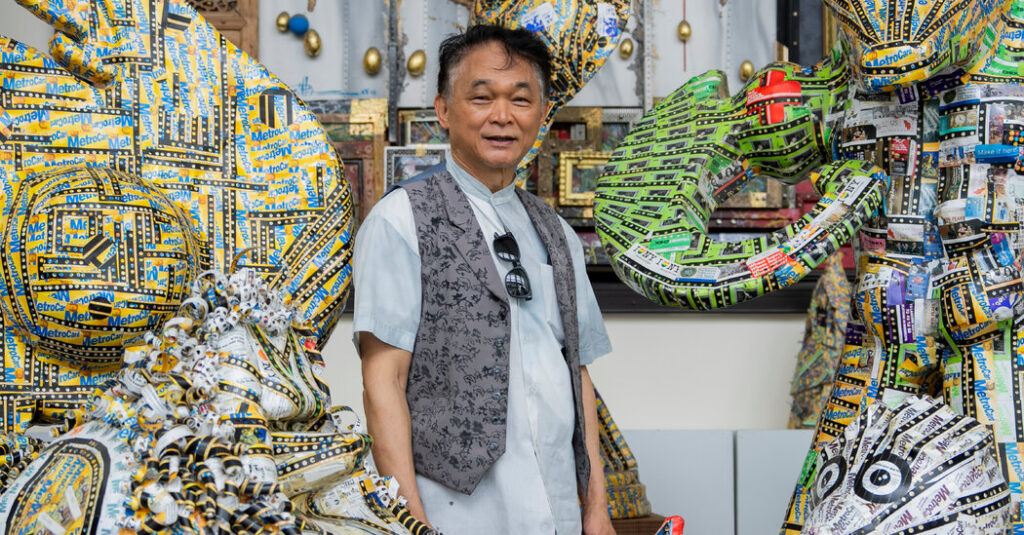

Consider Mr. Lin’s poodle, Hope, a four-and-a-half-foot-tall metal sculpture wrapped in more than 3,000 MetroCards. He has since collected more than 30,000 of the passes and has used them to build a menagerie, with a beast representing every month of the Chinese Zodiac.

“The story is the MetroCard,” Mr. Lin, 64, said about his medium, which debuted in 1994 and represents something egalitarian: Just about every New Yorker has one.

Or had one. In January, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which runs the city’s public transit system, ceased all sales of the iconic card and replaced it with a new tap-and-go system. Suddenly, the city’s plastic muse was gone.

On March 16, the New York Transit Museum will open an exhibit in Grand Central Terminal showcasing some of the city’s foremost MetroCard artists.

But the exhibit, called “Inspired by MetroCard,” is cold comfort for the artists enjoying a resurgence of interest in their work just as the cards are vanishing.

Some are resorting to buying leftover cards from price-gouging resellers. Others are counting and recounting their dwindling stashes to plan their next pieces.

Mostly, they are wondering how long they can keep going.

“They’re probably going through the stages of grief,” said Jodi Shapiro, the curator of the museum. “The worst thing for an artist is to have to stop completely.”

Thomas McKean, a children’s book author whose art will be featured in the exhibit, said he still had not come to grips with the end of the MetroCard.

“This has been my medium for a quarter of a century,” he said.

From his apartment in the East Village and a studio in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, Mr. McKean says he has used at least 100,000 cards to create collages and miniature models of New York iconography.

A Yankees baseball cap. A yellow taxi cab. A row of tenements. All were rendered in the limited color palette of the MetroCard — mainly yellow and blue, with hints of brown, white and black, though some varieties came in different colors. That was part of the fun, Mr. McKean said.

He still hopes to complete a series of collages inspired by his family’s history of immigration to New York and the buildings and places they occupied.

But he has known for years that the MetroCard’s days were numbered.

Its replacement, a contactless system called OMNY, began rolling out in 2019. But the pandemic delayed the system’s widespread use, and it wasn’t until last March that the authority set a drop-dead deadline of the end of the year for most commuters to make the switch.

He said he had tried to embrace the OMNY card, a thicker black-and-white piece of plastic without its predecessor’s panache. In his first go at using it in a creation, a collage of a modernist building near his home, he cheated and used bits of MetroCards to add some blue to the windows.

“It was like cooking with margarine instead of butter,” he said.

Mr. McKean, whose artworks have sold for more than $600 apiece, is planning to release new work in March, but his supply is low — about 5,000 cards, stuffed in boxes and plastic bags near his desk.

He used to restock on sites like eBay, but an order of 100 cards, which once cost him $30, can now run him hundreds of dollars.

Some artists were better prepared than others. Nina Boesch, 47, whose work, including a MetroCard collage of Katz’s Delicatessen, will be featured in the show, may have the biggest private stash in the city.

“Yeah, no, I’m good,” she said, as she tallied her hoard: about 90,000 cards. “I’ve got them scattered in different places because I’m so paranoid.”

She said she had made more money on MetroCard art in the last few months than she made all of last year. Tightening supply pushed her to raise her prices about 20 percent since October. Her smallest pieces cost $90, while her biggest pieces, 40-by-30-inch collages, can sell for about $4,500.

She credits her stash to the kindness of strangers, who’ve donated cards to her over the years, as well as the Broadway Green Alliance, a nonprofit group that has helped her collect expired cards from theater workers.

Juan Carlos Pinto, whose work includes MetroCard portraits of James Baldwin and Debbie Harry, said he was ready to say goodbye to the card, but not its perks. He said he had just sold a set of four portraits to a New York hotel for $8,000.

“I feel like a musician on the Titanic,” he said. “I’m one of the only artists who can pay their mortgage with the garbage of the subway.”

The M.T.A. ordered 3.2 billion MetroCards in the decades they were in use. Much of the remaining inventory, most likely tens of thousands or more, was recently stored in a high-security facility in Maspeth, Queens.

Aaron Donovan, a spokesman for the authority, said it had not determined what would happen to the remaining cards. But last summer, a transit official at the Queens facility said in an interview that many could be sent to an incinerator.

For Mr. Lin, who has spent two decades scavenging for the cards, the thought was painful. At his studio inside a factory for Crystal Windows in Flushing, Queens, he has plans to build a 10-foot-tall MetroCard Christmas tree, a tribute to the many people who have gifted him cards. He said he would need 15,000 cards, but he’s down to his last few hundred.

He would also like more cards to repair his Zodiac statues, some of which were damaged in 2024, when he displayed them inside the Oculus transportation hub in Lower Manhattan.

If he can get the statues in shape, Mr. Lin said he might seek $400,000 for the set and donate the proceeds to a charity he started that supports peace efforts in Ukraine.

Ms. Shapiro, the museum curator, said she sympathized with the artists, but doesn’t know the fate of the remaining cards.

“If I had a magic wand,” she said, “I would wave it.”

Stefanos Chen is a Times reporter covering New York City’s transit system.

The post They Use MetroCards to Make Art. They’re Starting to Run Out. appeared first on New York Times.