In July, Senegalese director Hussein Dembel Sow spent two days in Dakar shooting footage of his niece and a local actor for his latest project, a short film about a colorblind girl who undergoes hypnotherapy and, under the gentle guidance of her grandfather, paints fantastical worlds with her mind’s inner eye.

The six-minute film, titled “Rose,” will blend the real world with sophisticated visual effects, which would normally be difficult to accomplish in Senegal given the costly computer-generated imagery that makes up the crux of the project. But it’s expected to take just a few months and about $1,000 thanks to the aid of Moonvalley’s Marey artificial intelligence video model.

“If I didn’t have AI, I wouldn’t ever envision it,” Sow told TheWrap. “I would go make social dramas or things I could shoot with a camera on hand. I wouldn’t even try to make a movie about a magical reality.”

Sow had already made a name for himself by crafting an AI-generated video commemorating the massacre of Black African soldiers stationed at Thiaroye military camp in Dakar, a stirring music video with scenes that accurately depicted the look of the soldiers aiding the allied forces in World War 2 before getting cut down after their return to West Africa. The video garnered 1.9 million views on YouTube after it was posted in early 2024 and catapulted Sow onto the broader African creative scene, where he’s seen as a leading voice in the use of AI in media.

Sow is one of many who see AI as a way to even the playing field in filmmaking, his embrace contrasting starkly with Hollywood’s handwringing over the use of the technology, with many fearing it could decimate entertainment jobs and replace the creative pulse of cinema with a cold and calculating algorithm. With a large and diverse film landscape in Africa facing challenges like the lack of funding and infrastructure, creatives are seizing the kind of tools that allow for U.S.-like big budget special effects and post-production bells and whistles, and gaining attention along the way.

“It’s opening doors to content and stories that were not previously feasible,” said Alexandre Michelin, creator of the Knowledge Immersive Forum, a Paris-based organization dedicated to digital creation and the incorporation of new technologies like AI and VR.

But AI brings its own unique challenges to Africa’s creators. Artists there have to work with models that are developed in the U.S. and China, each with their own inherent biases, and must work doubly hard to ensure that their work is authentically African. Then there’s the cost to use the models, even something as simple as needing U.S. dollars to pay for access could hinder one’s ability to move forward on a project. With the technology so new, finding a community of likeminded enthusiasts has been critical. And while creatives there acknowledge the AI models still aren’t quite ready to handle full-fledged films, they’re excited about how rapidly they’re improving.

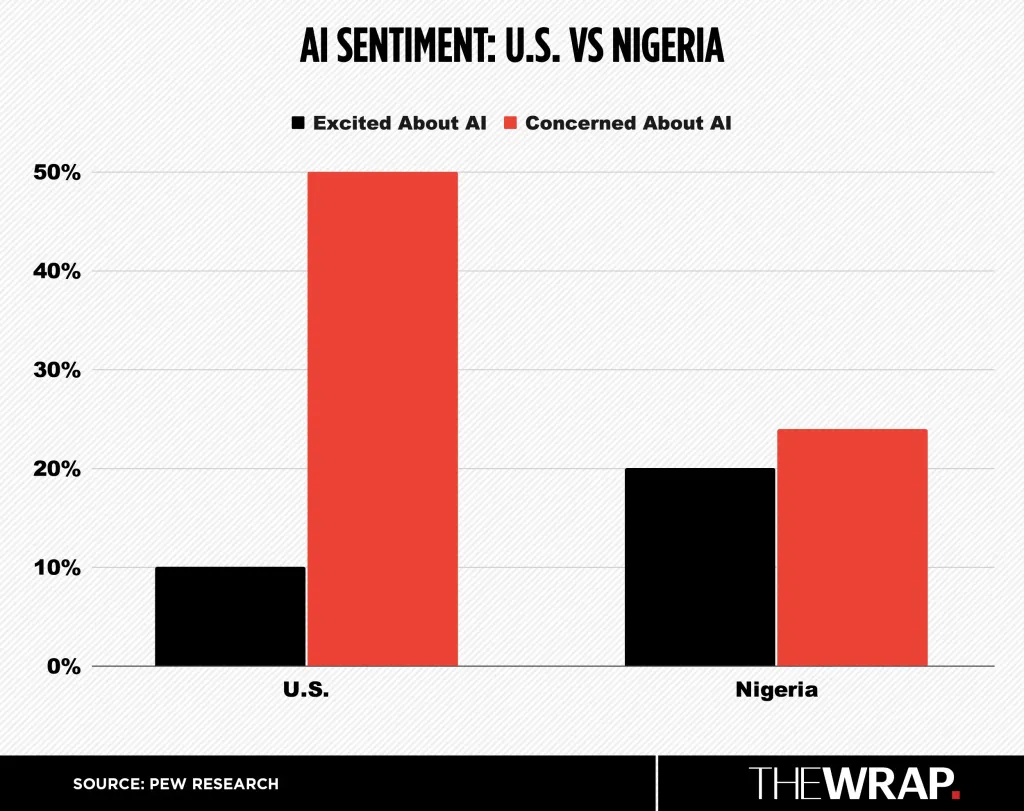

That openness is borne out by the differing attitudes that people have for AI based on regions. In Nigeria, one of the biggest tech and media hubs in Africa, the percentage of people who are excited about AI (20%) is double that figure in the United States (10%), while the percentage of Nigerians concerned about AI (24%) is less than half of Americans (50%), according to a Pew Research study published in October.

Within Africa, communities embracing AI and media have sprung up in cities that have the necessary technical infrastructure. In Nigeria, one of the dominant forces of cinema known as Nollywood, Lagos has been a hub for AI experimentation, while Dakar is another rising location. Sow believes Abidjan, the largest city in the Ivory Coast, where he moved to at the end of last year, is another city ready to embrace the technology — even if he has to create the movement himself.

“The rest of the world thinks this is their chance to catch up and surpass Hollywood,” said Amit Jain, CEO of Luma AI, which offers a video model used by studios around the world.

Or, as Sow bluntly put it: “They want to take Hollywood down and make film accessible to everyone.”

Shooting to fame

Sow got his start as an animator and started producing user-generated content with 3D animation tool Blender in 2015 before transitioning to live-action work and screenwriting. He embraced AI in 2023 when he started to get frustrated with filmmaking, which was still prohibitively expensive even if you could shoot video on your smartphone.

It’s his experimentation with tools that led him to create the AI-generated imagery for the Thiaroye 44 video. What hooked people wasn’t just the fact that AI was used, but the emotions it stirred when watching the 4-minute video set to a song by Senegalese rapper Dominique Preira, better known as DIP.

That’s also what got him on the radar of Bryn Mooser, CEO of AI studio Asteria. In a serendipitous moment, when Mooser opened his LinkedIn profile to contact Sow, he saw a message from the Senegalese filmmaker already in his inbox. What followed was a four-hour DM conversation that spanned all aspects of filmmaking, from quoting Stanley Kubrick to why Sow preferred to stay in Africa vs. moving to Hollywood to chase his dreams.

“Honestly, it was pretty magical,” Mooser told TheWrap.

A few months later, he and director David Darg, who co-founded media company RYOT with Mooser, hopped on a plane to Senegal to meet with Sow — and to bring a Red camera with a lens kit package.

The trio were keen to work together on something, and spent the night before writing the script for “Rose.” The next day, they tapped a local actor and Sow’s niece for the two day-long shoot.

After capturing the footage, Darg and Mooser returned home, with Sow still working on the AI portion of the film. Sow believes the project is a good illustration of how the technology will be able to allow more people to shoot proof-of-concepts, set up mood boards or just show their vision — regardless of where they come from.

Sow’s own work has resulted in plenty of Hollywood connections, even as he maintains a desire to stay in Africa. He’s also keeping busy traveling the world visiting film festivals and talking about how he infuses the human element into his AI projects.

“When I see the work Hussein is doing, him being able to integrate all these things to create an emotional narrative,” Angel Manuel Soto, director of “Charm City Kings” and “Blue Beetle,” told TheWrap. “The way he thinks about digital language … I truly respect him as an artist.”

Like Sow, Soto sees AI as a springboard for creatives in communities who don’t have the traditional studio resources. He served as an advisor to Asteria and took the lessons learned there to his company, Circa 1995, which provides AI and other VFX tools to creatives in Puerto Rico to help them develop their own intellectual property.

“They don’t have access to private funding, they don’t have access to distribution, they’re taking care of their parents or they cannot leave the island,” he said of the young talent he’s working with. “We have seen that (AI) has opened the opportunities of creativity within these communities.”

Owning your digital narrative

Sow isn’t the only African creative making a name for himself with AI. For Malik Afegbua, what turned out to be an outlet to deal with the sadness over his mother suffering a stroke ended up being an international social media phenomenon. In early 2023, he had posted a series of supposed photographs of elderly African models walking the runway of a fashion show on Instagram, which quickly got noticed by Western outlets like CNN and BBC.

Only, they weren’t photos and didn’t feature real people. Afegbua used AI to generate the images, taking pains to create images of people and fashions that were faithful to what he saw around him in Lagos.

The early work showed him that as powerful as these AI models were (he said he started with Midjourney, but has used others since), they lacked accurate details when it came to people with African descent, and what was available fell into tropes. That started Afegbua on a quest to fine tune the models himself and train them with his own data.

“If you know about the perception of Africa and Africans in the world, it’s very stereotypical,” Afegbua told TheWrap. “When you think about how we change that narrative, I need to refine things from scratch.”

“Many of the people who engage with (AI models) say the representation is not good,” Michelin said, noting there are distinctions between people in South Africa and Senegal, but none of those nuances are captured. “They don’t recognize their faces.”

That problem has led to Afegbua starting his own moon shot (to borrow some tech parlance): the creation of African LLM – V1, an AI model fed with cultural data he’s been collecting over the past year, including interviews, scans of historical sites, 3D imagery and drone shots. He’s gone into villages with more insular cultures and convinced them to tell their stories with him.

“If you don’t share it with me, someone else will tell your story for you, and it won’t be accurate,” was what he said to these communities, many of whom shared their stories and traditions to an outsider for the first time.

He said he’s taking these steps now because if nothing is done about the cultural bias in models, it’ll just get worse over time. He’s taken the issue to the national level, consulting with the minister of foreign affairs on AI policies and even training government officials on AI systems.

For creatives in Africa, being able to type a prompt asking for a Nigerian businesswoman and getting an image they recognize means everything when it comes to the authenticity of the content they’re creating.

“Representation within AI will probably have to evolve to take into account the differences in the different ethnicities of Africa,” Michelin said. “The question of representation is important to make it relevant to more people. For creative people it’s super important.”

Creating a community

While individuals have been exploring AI, with some like Sow and Afegbua garnering international attention, there are few gatherings in Africa where people exchange ideas, ask questions or simply just commiserate with others.

So Obinna Okerekeocha, director of content at Nigerian banking company Moniepoint MFB and digital creator, started one of his own.

In April, Okerekeocha declared he would create Nigeria’s first-ever AI-centric film festival. After bootstrapping the event and working for five months, he launched the Naija Artificial Intelligence Film Festival in September. The event received nearly 500 submissions from around the world and counted in its ranks faculty members Afegbua and Sow.

Beyond having a place for people to screen and discuss AI films for two days, the film festival also helped kickstart a 500-strong community of AI-focused African creatives that he has fostered on WhatsApp.

“I never would have met these guys if I didn’t put on the film festival,” he said.

The community isn’t just valuable as a place for ideas, but also a way to help each other find opportunities.

While AI offers access to tools that can mimic the kinds of high-end production values seen in big-budget Western productions at a fraction of the expense, the technology isn’t free. For many, the cost to experiment with AI remains a significant barrier. Some models require credits that need to be purchased in U.S. dollars, which puts Nigerians at a disadvantage, Okerekeocha said.

Access to funding remains a challenge for many, even in Nollywood, Nigeria’s vibrant film industry, which he said still has problems with theatrical distribution and where power and resources are concentrated.

“AI is not free,” Michelin said. “It’s costly. The cost is even worse in many African countries.”

Okerekeocha said one company, AiStudio.ng, has made tools available that take Nigerian Naira, which has made a difference in accessibility, an example of the work people are doing to make AI tools more accessible. He has also helped connect individuals with creative programs run by companies like Runway, whose AI models are used by Hollywood studios, in an effort to give them exposure to the technology.

“My driving force is how I can empower young people to discover a new way to express themselves and make money from it,” he said. “What is the future of African storytelling? It lies at the intersection of art and technology.”

An unpredictable path forward

Hussein moved to Abidjan after taking a job as director of AI production for marketing firm Agence X — the first such department at an ad agency in Africa. His initial project involved the production of a 100% AI-generated commercial for Ivory Coast water brand AkwabaO featuring a soccer player facing off against a herd of elephants (it’s a ridiculous premise, but surprisingly works).

When not working his day job, he continues to work on “Rose.” His goal is to release the film in Los Angeles or Dakar in the next three months, and hopes it will qualify for Academy Award consideration in the Short Film category.

Hussein is less concerned about AI taking jobs and compares the technology to YouTube and Spotify, big platforms that ultimately made it easier to distribute content. Like those platforms, AI could spur the creation of a wealth of new films that aren’t restricted by the limitations of financing concerns, distributors or producers.

“If you can write it, you can make it,” he said.

But he also acknowledged it could be a while before that total disruption will happen. While the technology continues to rapidly improve, getting to the point where AI can generate whole movies could take decades. Even if the first 90% took little time, the final 10% to fully get past that uncanny valley could take much, much longer.

“Technology is very unpredictable, and it’s not linear,” he said.

But he looks forward to the day when someone from Africa can create a Hollywood-style blockbuster, but from Africa. “I love ‘Black Panther,’ but even though it talks about Africa, it’s made by an American and I see a lot of clichés and stereotypes,” he said. “Maybe in 10 years, you’ll see African movies competing at the box office with American films,” Sow said.

The post AI in Africa: A Creative Revolution Challenging Hollywood Fears and Limitations appeared first on TheWrap.