When Bad Bunny emerged from a row of towering sugar cane stalks to kick off his Super Bowl halftime show performance, it might have been easy to read the set design as little more than a lush backdrop: a tableau of Caribbean paradise imported to the Bay. Bad Bunny certainly didn’t explicitly acknowledge the sugar cane: He was too busy singing “Tití Me Preguntó,” a brash ode to his sexual prowess, which has racked up a billion streams both on Spotify and YouTube.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

But like everything that Bad Bunny does, the scene cut deeper than its appearance. The Puerto Rican singer surrounded himself with men and women cutting down the stalks, summoning the territory’s centuries-long colonization, in which sugar played a central role. Spain brought the crop to the island in the 1500s and set up massive plantations manned by slaves. At the end of the 19th century, the United States took the island by force and set up its own lucrative sugar colony, with mainland corporations controlling a significant share of production and reaping massive profits.

For rulers abroad, the Puerto Rican people were mostly a nuisance to be managed. But despite all of this, Boricuas found ways to thrive. They created their own music, food, oral traditions and businesses, forging a fiercely resilient and joyous culture that has now been exported to the world. And Bad Bunny, in just a few minutes of television, communicated all of this: the oppression, the ingenuity, the joy of his people. Eighty years after the government made it illegal to fly a Puerto Rican flag or sing a patriotic tune, there was Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio, proudly waving that flag and singing his proudly Puerto Rican songs, surrounded by Latinos carrying their own banderas on America’s biggest stage.

The show arrived against the backdrop of the U.S. invading another Latin-American state to gain control of its resources; and of masked government agents abducting Latinos from their own homes. Last week at the Grammys, Bad Bunny made a pointed political statement, saying “ICE out.” He made no such declaration on Sunday—at least with his words.

But Bad Bunny’s halftime show was a fierce act of resistance, and a triumph on many levels. It was an exuberant exercise in spectacle, stagecraft, choreography and camera work; you could have not understood a single word and still had a blast. It was also a sharp cultural and history lesson of Puerto Rico’s past and present; of what it means to live under colonization. Above all, it was a 13-minute capstone to why Bad Bunny is—and deserves to be—the biggest pop star in the world.

Puerto Rico in the Bay

While Bad Bunny has now been famous for nearly a decade, most of the songs he performed in his halftime show were from his most recent album: 2025’s Debí Tirar Más Fotos. Before that album, Bad Bunny seemed to be on the cusp of ascending to the pinnacle of mainstream American success: moving to Hollywood; dating a Kardashian-adjacent celebrity; fighting Brad Pitt in an action movie. Fans wondered whether he would start singing in English.

Instead, the album saw him retreating more deeply into Puerto Rico than ever before, plumbing its folk music traditions like plena and bomba. In December 2024, he told TIME that the album represented not Puerto Rico’s famous beaches, but its inner mountains, where life was less postcard-picturesque but more textured and communal. “We’re looking for a refuge in the countryside. A resistance in that way,” he said.

Read More: Bad Bunny On Debí Tirar Más Fotos

Somehow, this insular, resolutely regional album ended up yet another peak in his storied career. Fans across the globe loved its authenticity, its complex rhythms, the playfulness oozing out of his collaborations with young musicians from San Juan music schools. In 2025, he reclaimed his title as the most streamed artist on Spotify, generating 19.8 billion streams. Last week, Debí Tirar Más Fotos won album of the year at the Grammys.

Bad Bunny carried the album’s joy, communal nature, and cultural specificity into the halftime show in full force. Characters on stage sold piragua (shaved ice); painted nails; played dominos; built shelters with cinderblocks. Maria Antonia Cay, who owns the iconic Latino social club Toñita’s in Williamsburg, posed fiercely inside of a perfect storefront replica of her Brooklyn bar. All the while, his dancers carried much of the energy: they twerked to “Yo Perreo Sola,” an ode to female independence on the dancefloor; went crazy to “Gasolina,” the Daddy Yankee reggaeton classic; and gracefully glided and twirled across the floor to his salsa song “Baile Inolvidable.”

In one of the show’s most poignant moments, Ocasio handed one of his Grammys to a little Latino boy. Many viewers noted the young actor’s resemblance to the 5-year-old Liam Conejo Ramos, who was arrested with his father outside their home in Minneapolis and sent to a detention center in Texas. (Conejo, of course, means “bunny” in Spanish.)

Celebrity Appearances

All of this close attention to cultural detail meant that when celebrities showed up, their appearances didn’t feel forced. Instead, they offered proof as to how alluring Puerto Rico is to the rest of the world. During “Yo Perreo Sola,” the camera flashed over Pedro Pascal, Cardi B, Jessica Alba, Karol G, and others, who were not there to promote anything, but just bask in the greatest party on Earth.

The big surprise guest of the show was Lady Gaga, the star of Super Bowl LI, who sang a salsa version of her song “Die With a Smile” before joining Bad Bunny for a dance, her face absolutely beaming with joy. (This was a shrewd moment of reverse assimilation: While conservatives called for Bad Bunny to sing in English, instead he got a major white female pop star to adapt her song into salsa.) Then there was Ricky Martin belting “Lo Que Pasó a Hawaii”—a song off of Fotos, which laments the plight of another U.S. sugar colony, Hawaii.

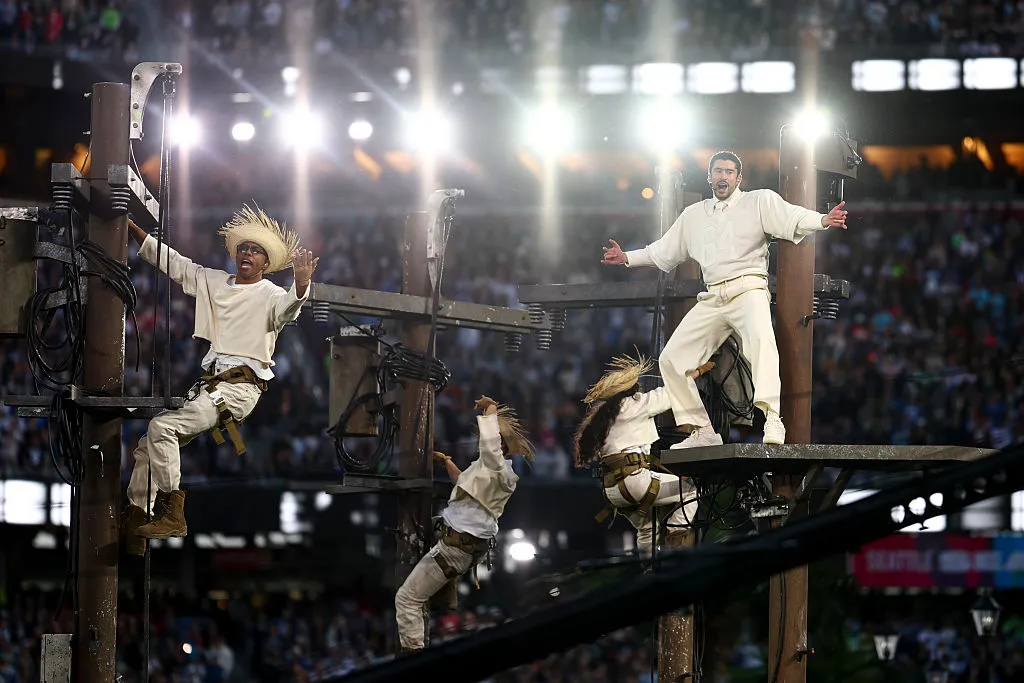

The final major setpiece of the show came during “El Apagon,” a high-energy electronic dance song released in 2022. Like the rest of the show, it was mesmerizing even without any understanding of the lyrics: Ocasio was surrounded by dancers dressed as maintenance men fixing power poles high in the air, sparks flying all around them, in a seeming nod to the other aerial acrobatic feats of Super Bowls past, including those of Lady Gaga herself.

But the song—and the stagecraft—also served to call attention to Puerto Rico’s frequent blackouts, which worsened following the private takeover of the island’s grid. On Christmas Eve 2025, yet another blackout left thousands of Puerto Ricans in the dark. As Bad Bunny’s dancers pretended to struggle to fix the power, Bad Bunny clambered up to the top of one pole, pointing directly into the camera, his expression seemingly conveying that it was up to him—and Puerto Ricans—to find solutions themselves.

In the lead-up to the performance, many conservative commentators expressed concern that Bad Bunny wasn’t American enough; that his music didn’t fit the stage. (Never mind that Puerto Ricans are American, and that the Super Bowl has also hosted plenty of non-Americans, including U2, Paul McCartney, and the Rolling Stones.) President Trump even said he would skip the show, calling his selection a “terrible choice.” (Following the performance, Trump doubled down, saying “nobody understands a word this guy is saying,” despite the fact that, well, around 50 million people in the U.S. alone do.)

But Bad Bunny has always thrived precisely because of his refusal to assimilate or cater to the mainstream. His halftime show exemplified this fearless approach; to layer genuine education upon mass spectacle, and to slyly rail against injustice with humor and joy. He ended the show by projecting a message onto the Jumbotron: “The only thing more powerful than hate is love.”

The post Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl Halftime Show Was an Exuberant Act of Resistance appeared first on TIME.