The Civil War isn’t what it used to be. Instead of the romantic version, a “good war” of courage and glory, that emerged in the conflict’s immediate aftermath, or the post-civil-rights-era emphasis on the war as the vector of liberation for 4 million enslaved African Americans, a more recent direction has been labeled the “dark turn.” Grim rather than celebratory, it has chronicled the war’s cost and cruelty, exploring subjects such as death, ruins, starvation, disease, atrocities, torture, amputations, and postwar trauma, as well as a freedom that was rapidly undermined.

W. Fitzhugh Brundage’s gripping new book, aptly titled A Fate Worse Than Hell: American Prisoners of the Civil War, represents an essential contribution to this rethinking in its account of what was perhaps the most horrifying realization of the suffering and inhumanity the war produced. But Brundage, who teaches at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, does more than expand our understanding of a neglected aspect of Civil War history. His study offers a window into larger questions—about the evolution of laws of war and the definition of war crimes, about the ethical responsibility of combatants, about the growth of the nation-state and its attendant bureaucracy, and about the defining presence of race in the morality play of American history. As one Vermont infantryman wrote from a Confederate prison camp, “Here is where I can see human nature in its true light.”

At the beginning of the fighting, in 1861, no one anticipated that more than 400,000 men would become prisoners of war and that at least half of these would spend extended time in sites of what we would now call mass incarceration. The odds of being captured by the enemy in World War II were 1 in 100. In the Civil War, they were 1 in 5. As Brundage observes, three times as many Union soldiers died at the Confederate camp in Andersonville, Georgia, as at Gettysburg. Overall, approximately 10 percent of the war’s deaths occurred in prisons.

[From the December 2023 issue: Drew Gilpin Faust on the men who started the Civil War]

But prison camps attained this scale and significance only gradually. Both sides were initially uncertain about how to handle enemy captives. “What should be done with the prisoners?” the Richmond Whig asked. Treatment was largely ad hoc and depended to a considerable degree on individual commanders, but customarily prisoners would be exchanged or placed on parole—granted their freedom but required by oath not to return to military action. Rooted in assumptions about gentlemen’s honor and the integrity of pledges, the notion of parole now seems quaint, and it disappeared as the brutality of the war escalated. Some members of Abraham Lincoln’s Cabinet even argued for executing Confederate prisoners as traitors, but Congress and the public exerted pressure on the president to establish procedures to facilitate the return of captured Yankees. Formal provisions for the exchange of prisoners was not agreed upon until the summer of 1862, delayed by the Union’s reluctance to take any action that implied recognition of Confederate nationhood. Under the terms of the Dix-Hill agreement, some 30,000 prisoners were returned from captivity by the fall, but the formal exchange arrangement was soon upended.

The Emancipation Proclamation, issued in preliminary form in September 1862, provided for the recruitment of Black troops into the Union Army. Viewing this new policy as equivalent to fomenting slave rebellion, the South rejected any exchange of Black soldiers and did not extend them the protections of prisoners of war. They might be killed on the battlefield even after they surrendered, or remanded into slavery, or consigned to camps where they endured disproportionately harsh treatment.

Lincoln was resolute in his resistance to these measures. If Black soldiers could not be exchanged, no soldiers would be exchanged. The Dix-Hill agreement was suspended, and the number of prisoners of war grew exponentially; the result was camps the size of cities and untold misery for thousands of men in both the North and the South. Only during the last months of the war, with slavery disintegrating and northern victory all but assured, did exchanges resume.

Brundage characterizes the creation of the camps as an “innovation,” describing them as “experiments in custodial imprisonment” that exceeded anyone’s prewar imagination. These were modern inventions made possible by the introduction of railroads to transport prisoners long distances from battlefields, and by the growth of administrative and organizational structures required to manage not just mass armies but hundreds of thousands of prisoners. Although they emerged out of war-born imperatives, the camps were, he insists, a choice made by northern and southern policy makers alike, motivated by assumptions and purposes for which Brundage argues they must bear responsibility.

Both sides believed that any sympathetic act toward the enemy would represent an insult to their own soldiers. The Union commissary general in charge of prison administration proclaimed that “it is not expected that anything more will be done to provide for the welfare of the rebel prisoners than is absolutely necessary,” and that work on a prison camp under renovation should “fall far short of perfection.” During spring and summer months, he mandated that any clothing distributions include neither underwear nor socks.

But whatever the moral and logistical shortcomings evident on both sides, Brundage draws a clear distinction between North and South. “By any reasonable measure,” he judges, “Confederate prisoners were better kept than their Union counterparts.” Southern officials, he concludes, “never fully accepted the obligation to provide for prisoners of war.” Union prisoners were regarded not as human beings but as “a security liability that imposed no ethical imperative.” The South housed its captives in ill-adapted existing spaces. Richmond’s Libby Prison was a converted tobacco factory; the Salisbury, North Carolina, prison had been a textile mill; camps in Montgomery and Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and Macon, Georgia, were former slave jails. At the notorious Andersonville camp, no structures were provided at all. Men were not even issued tents but scrounged to procure shirts, blankets, or other bits of cloth to drape over sticks of wood to create what they called “shebangs.” Those unable to find cloth or wood dug holes in the ground.

The Union, in contrast, erected barracks and designed purpose-built enclosures for this new experiment in large-scale imprisonment. Those overseeing Union prison camps acknowledged that providing food and shelter for captives was indeed a moral obligation, even if on numerous occasions they failed to deliver adequately on that commitment. Yet the 25 percent death rate at the North’s worst prison, in Elmira, New York, came close to that at Andersonville (29 percent); overall, the mortality rate was 16 percent for Union prisoners and 12 percent for Confederates. Cruelty and corruption recognized no regional boundaries, and officials on both sides seem to have come closer to despising than sympathizing with their suffering captives.

There is a long tradition—born in the midst of the war itself—of accusation and debate about which side behaved worse. Defending the South’s treatment of its prisoners became a central theme for the neo-Confederates of the Lost Cause as the movement to rehabilitate the South emerged in the late 19th century. The blame for the surge in incarceration in 1863 and beyond should rest with the Union, they contended, for it was the North that halted the prisoner exchange. Pressing the advantage of their superior numbers, the North mercilessly kept captured Confederates in prison camps to prevent them from returning to the field to replenish the South’s diminishing ranks. The North’s decisions about prisoner exchanges were based on military calculations, not benevolent concern for Black captives. The South, they argued, did its best with its prisoners, given the scarcities of resources available to Confederate soldiers and citizens alike, scarcities they blamed on the Union effort to destroy the southern economy by blockading ports.

Professional historians in the early 20th century were not as explicitly partisan as the United Daughters of the Confederacy and their supporters. Yet, influenced by William B. Hesseltine’s field-defining Civil War Prisons, published in 1930, they adopted a kind of everybody-inevitably-made-mistakes approach that exonerated Confederates of any intentional moral failings. At the same time, they attributed to the North a vindictiveness arising from “abolitionist propaganda” that exaggerated Confederate prison atrocities.

The first comprehensive—one might say encyclopedic—study of prison camps since Hesseltine, Brundage’s book challenges these arguments head-on and assigns responsibility to the South’s unwavering commitment to slavery and Black subordination. Post-civil-rights-era attitudes about the equality of African Americans have prompted a different assessment of who caused the breakdown in prisoner exchanges, and thus bore the onus for the suffering and death that ensued: It was the South’s refusal to recognize Black soldiers as free men and thus treat them as prisoners of war, not Lincoln’s principled reaction to this Confederate policy, that produced such large numbers of Civil War captives. And Brundage ensures that his readers will not dismiss the record of prison atrocities. Although he offers examples of miseries from both northern and southern camps, his portrait of Andersonville leaves the most vivid impression of what the war’s moral compromises came to mean.

Andersonville was not created until February 1864, but in the months that followed, as many as 90 trainloads, containing 75 men to a boxcar, soon established its unprecedented scale. The camp consisted of a stockade erected around a 16-acre field by 200 enslaved workers commandeered from nearby plantations. Andersonville was designed to hold 10,000 prisoners, but its population reached as high as 33,000. The camp had no sanitation system, no barracks, no clothing allocations, and scant rations distributed uncooked to men without pans or utensils or firewood. Disease—scurvy, typhoid, dysentery—was rampant among prisoners, but medical treatment was worse than inadequate. In the prison hospital, made up of dilapidated tents, 70 percent of the patients died. When Confederate officials arrived to inspect the camp in May 1864 and again that August, they were shocked by what they saw. Nearly 13,000 men lie buried in the Andersonville National Cemetery, which the nurse and future founder of the American Red Cross Clara Barton helped establish on the site at the end of the war.

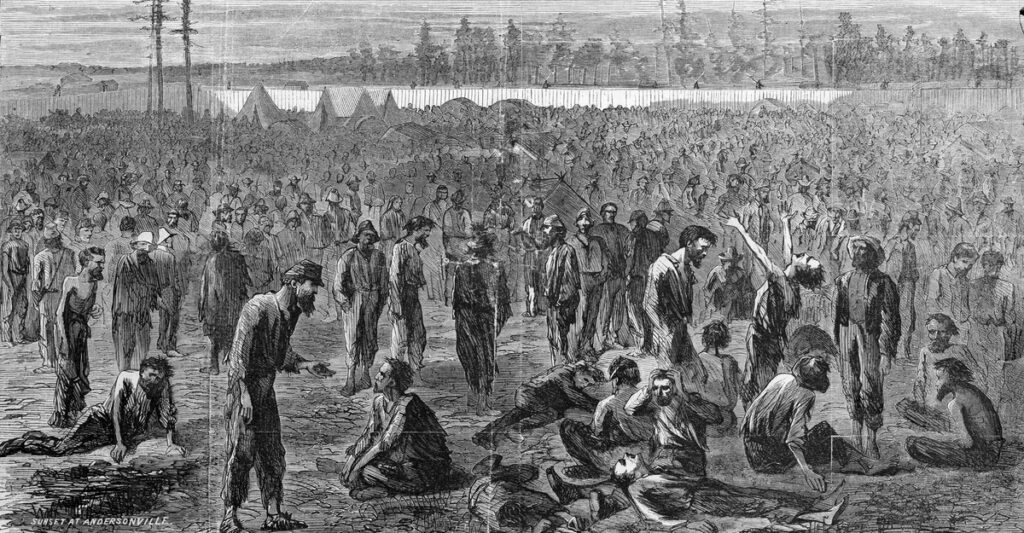

A great strength of Brundage’s study is the breadth and depth of his research; he makes deft use of a wide variety of evidence beyond the official records on which much earlier historical work on Civil War prisons has rested. He opens the book with a consideration of a series of photographs of Andersonville that in themselves make minimizing the horror and suffering impossible. A photographer from Macon, 60 miles away, seemingly compelled by pure curiosity, spent an August day in 1864 taking panoramic pictures of life within the camp stockade—the ground obscured under a sea of shabby improvised shelters; the swarm of prisoners gathered to receive rations; the men seated bare-bottomed over an open trench that would carry their waste into the same stream that provided their drinking water. Illustrations throughout the book support Brundage’s insights and arguments.

Yet perhaps even more striking than the pictures are the words taken from prisoners’ letters, diaries, and memoirs. Brundage accompanies his narrative of evolving prison policies with voices and stories of individual men. “Are we to be exchanged, or are we to be left here to perish?” asked Orin H. Brown, William H. Johnson, and William Wilson, three Black Union sailors, in the summer of 1863, still packed into a crowded Charleston prison half a year after their ship had surrendered and their captured comrades, all of them white, had been exchanged. Somehow their petition—miraculously evading Confederate interception and traveling, via the Bahamas, to Washington—arrived on the Navy secretary’s desk, though they likely weren’t released until the end of the war. For Frederic Augustus James, a prisoner at Salisbury, unreliable mail was one of many sources of agony; he learned of his 8-year-old daughter’s death five months after the fact, a succession of his wife’s letters having never reached him. Four months after his transfer to Andersonville, he died of dysentery.

William Hesseltine and his followers had dismissed such sources as at best partial and at worst partisan in their exposition of the cruelties inflicted by their wartime enemies. Brundage approaches these materials with an appropriately critical eye, demonstrating their consistency with other records and their value in providing deeper human insight into prisoners’ experiences. What Hesseltine claimed as objective history, Brundage both tells and shows us, was in actuality far from objective; it placed the story in the hands of the official record keepers while silencing those who were the victims of their decisions and policies. Incorporating their accounts, Brundage provides his readers with a far richer and more complete version of the past.

At the same time, he casts his book as being about the present and the future as well. Mass internment, as he portrays it, is a product of modernity, made possible by technology and growing organizational and logistical capacities. But it was also a deliberate choice, a callous and conscious decision. “What combination of institutional authority and procedures,” he asks, “eroded the moral inhibitions of officials, commanders, and camp staff, thereby making it easier for them to abandon the responsibility they might otherwise have felt to ease the suffering of the fellow humans” at Andersonville? It is hard to look at the most terrible pictures of captives ultimately returned to the North without seeing in one’s mind the photographs of those liberated from Nazi concentration camps eight decades later.

Yet the demands of modernity produced some humane outcomes that also presaged the future. The dilemma of how to deal with Civil War prisoners served as a catalyst for General Orders No. 100, issued by the War Department in 1863. It was the first systematic codification of the rules of war and became the foundation for modern international humanitarian law. It led to the trial and subsequent execution at the war’s end of Henry Wirz, the commander at Andersonville, for conspiring “to impair the lives of Union prisoners.” Northern prosecutors had hoped to charge top Confederate leadership, including President Jefferson Davis, in a series of postwar trials. In the end, Wirz was their only major conviction, because southern outrage and northern demands to forgive and forget brought an end to the legal effort. But Wirz’s trial represented the origin of modern prosecution of war crimes.

“Military necessity,” General Orders No. 100 directs, “does not admit of cruelty.” In the Civil War’s prison camps, it did just that. Yet the statement encodes an aspiration and an expectation, if not always an enforceable law. Born of Civil War suffering, international humanitarian law demands, as does Brundage’s important book, that we recognize cruelty as a choice.

This article appears in the March 2026 print edition with the headline “Deadlier Than Gettysburg.”

The post Deadlier Than Gettysburg appeared first on The Atlantic.