A few weeks back, in the run-up to Christmas, my family was doing what it always does during the holiday season: watching Home Alone. And, around the time that Joe Pesci and Daniel Stern’s Wet Bandits began plotting their break-ins, I began wondering something: Were home robberies really so common in 1990, when the film was released, that audiences wouldn’t blink at the idea of a comedy based around home burglary?

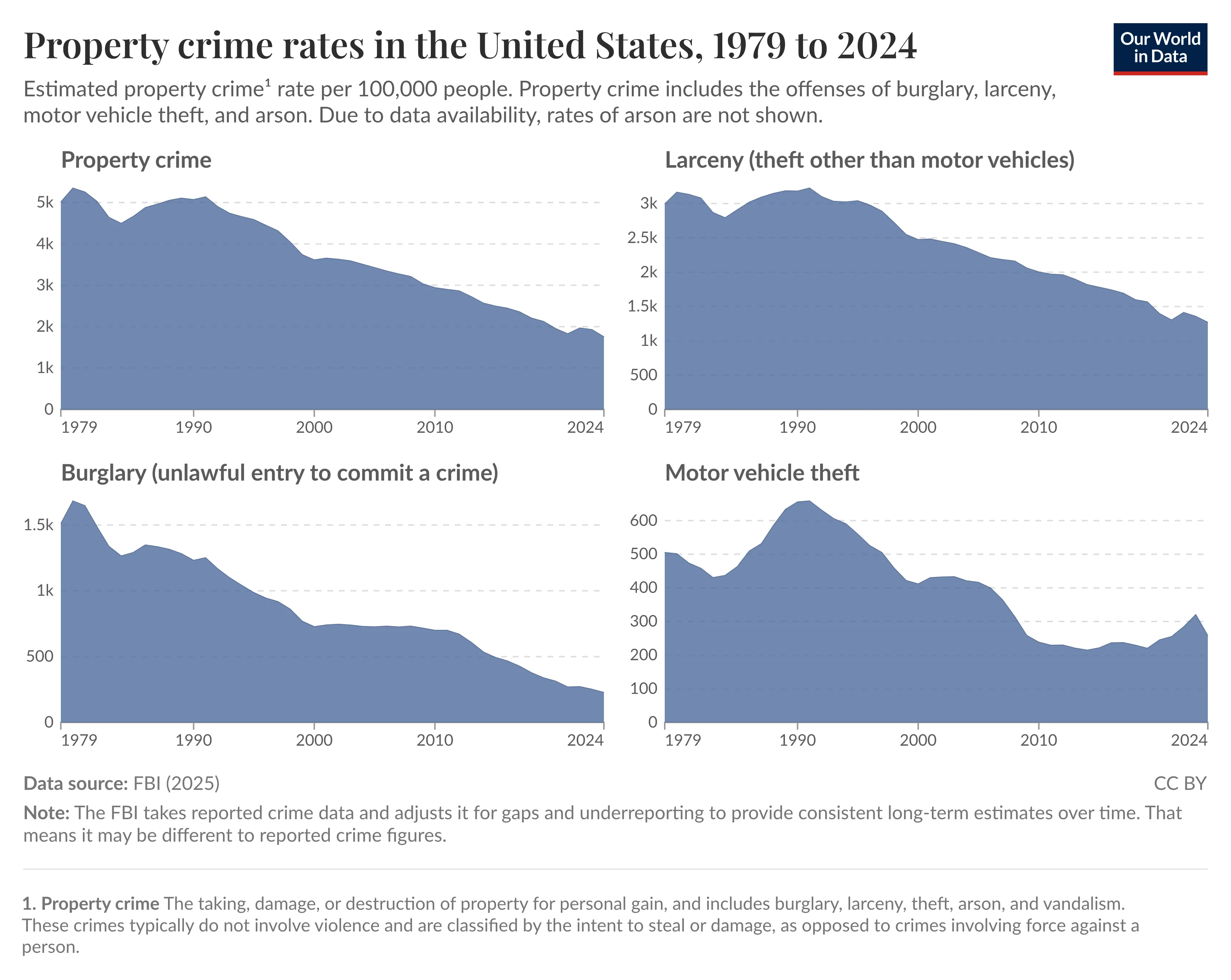

In 1990, in the Chicago suburb of Winnetka where the film is set, there were 53 burglaries, the vast majority of which were in residences like the McAllisters’ house in the movie. That adds up to a rate of 435 robberies per 100,000 people, which was actually fairly low for the time. But in nearby Chicago, there were more than 50,000 burglaries, or around 1,800 per 100,000 people, that year. The nationwide burglary rate was over 1,200 per 100,000 people — part of an overall property crime rate that was near the highest the US had ever recorded.

So, yes, the idea that a couple of bandits might break into your home while you were off on a Paris vacation wasn’t far-fetched. (Although given that the McAllister family were so disorganized they twice lost one of their kids on Christmas vacation trips, I’m not all that confident about their home security approach.)

But when Home Alone is remade — as I’m certain a remake-obsessed Hollywood will do eventually — they might need to change up the premise. Nationwide, burglary rates have fallen by more than 80 percent since 1990. Chicago has seen rates fall by similar levels, a story that is all the more remarkable given just how high those rates were in the 1990s. Wealthy Winnetka had less far to drop, but it’s still down by over 60 percent.

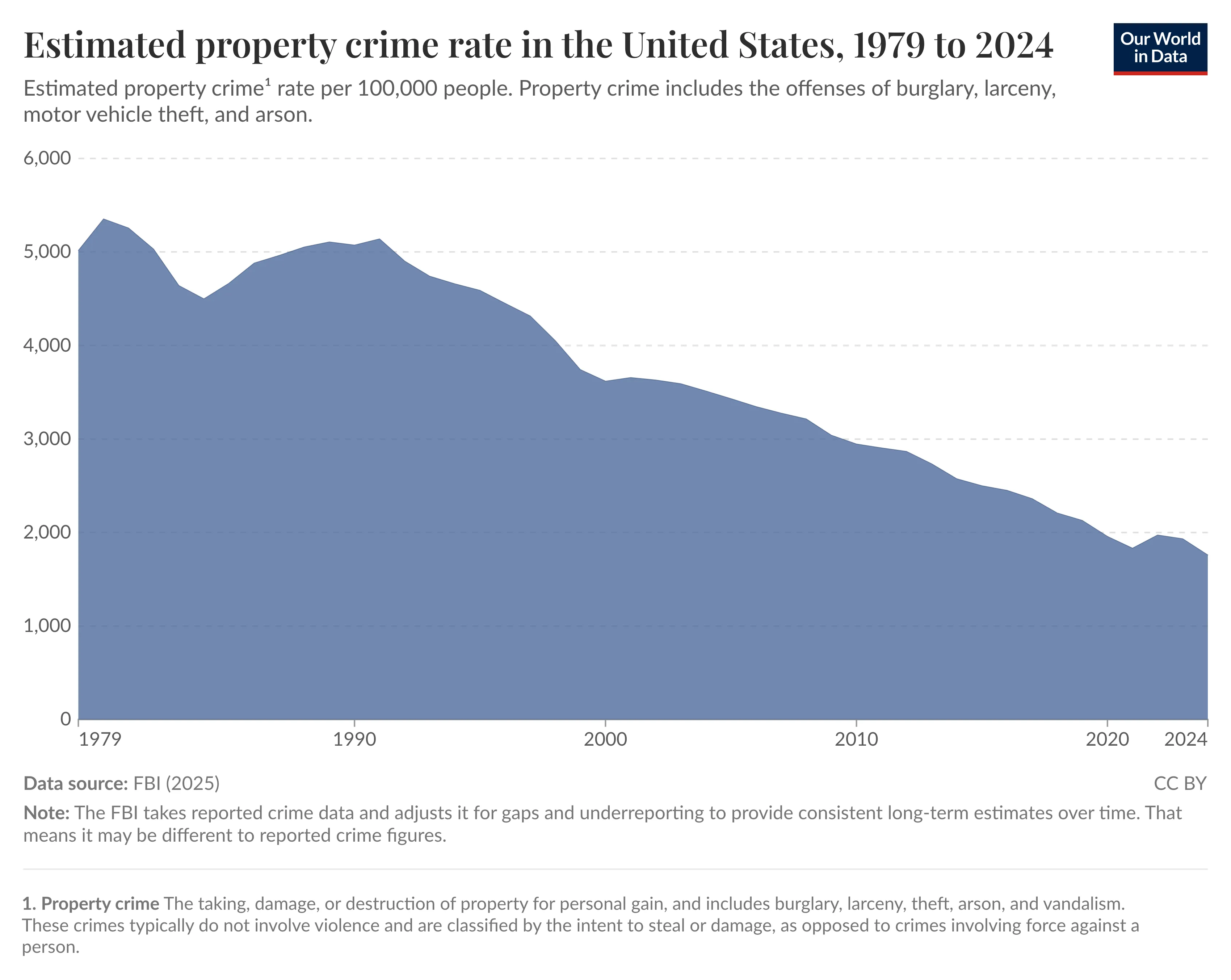

While the historic drop in violent crime in the United States has gotten a lot of attention recently, including in this newsletter, the dip in property crimes like robbery, burglary, and motor vehicle theft has gone under the radar. The overall property crime rate has fallen by 66 percent in the US since 1990, even steeper than the decline in violent crime, and the lowest level since national data began in 1976. And while this has largely been a steady, long-term trend, there was a 9 percent decline between 2023 and 2024 — the sharpest single-year decline on record.

For our stuff, as well as for our lives, there’s an argument to be made that Americans are safer now than they have ever been.

The bad old days

To understand what’s changed, it helps to remember what “normal” looked like at the end of the 1980s and the start of the 1990s. In that period in many cities, property crime was like background weather: something you planned around and simply had to live with, even if you didn’t talk about it every day.

Key takeaways

- Property crime in the US has fallen 66 percent since 1990, to the lowest level since national data began in 1976 — an even steeper decline than the much-discussed drop in violent crime.

- Burglary rates have plummeted more than 80 percent nationwide since 1990, driven by better locks, alarms, outdoor lighting, and the rise of doorbell cameras and informal neighborhood surveillance.

- Stealing stuff got a lot less profitable. Consumer electronics are cheaper, easier to track, and harder to resell, while the decline of cash means both muggers and burglars face lower payoffs and higher risk.

- The 2023–2024 drop was historic: Property crime fell 9 percent in a single year, the sharpest annual decline on record.

- But crime didn’t vanish — it changed form. The FBI logged $16.6 billion in internet crime losses in 2024, and an estimated 58 million packages were stolen that year, suggesting old-fashioned theft has partly migrated online.

Nationally, the overall property crime rate was just over 5,000 incidents per 100,000 people each year around 1990. If you do the math, that means the country was recording roughly one property crime for every 20 residents on average. Of course, the average wasn’t how people lived. Then, as now, crime could be highly concentrated in some neighborhoods and virtually absent in others. But that’s still a staggering level of routine predation.

On a dollar level, the average residential burglary in 1990 resulted in a loss of around $2,800 to $3,400, while total losses for all property crime was nearly $40 billion. (Both numbers are adjusted for inflation.) But there was also a price on human lives. By one estimate, roughly one in four robberies — like your classic street mugging — resulted in some form of physical injury to the victim, while roughly one in 10 of all murders occurred in the course of a felony like robbery and burglary. Based on homicide numbers at the time, that meant as many as 2,500 people may have lost their lives due to incidents that began as simple thefts or robberies.

And these numbers may just touch the surface. Police-reported crime is partly a measure of crime and partly a measure of reporting crime. In a high-crime environment, people often stop calling the police for “smaller” thefts — because the expectation becomes that nothing will happen, or because the hassle isn’t worth it. So even these ugly numbers likely understate how saturated daily life could feel with property crime.

All of which raises the question: What changed? It’s probably not because Americans suddenly became nicer. Instead, it’s due to a confluence of factors in how we police crime, how we protect ourselves from it — and even the kind of stuff we own now.

Crime of opportunity

The bottom line is that we changed our environment in a way that made burglary and robbery harder to pull off, less profitable, and more likely to fail.

For one thing, homes and apartments are simply harder to burgle than they used to be. We have better door and window locks. Better frames. Better outdoor lighting. More apartment buildings have controlled entry, buzzer systems, and cameras. Alarms got cheaper. And now, in many neighborhoods, a kind of informal surveillance mesh exists: doorbell cameras like Amazon’s Ring, building cameras, storefront cameras, even the scourge that is Nextdoor. The Wet Bandits wouldn’t stand a chance today.

A paper published in 2021 directly links the startling drop in burglary to security improvements like the above, which helps explain why property crime kept dropping in diverse cities, across different presidencies, up and down economic cycles, almost without stopping. Burglary is an opportunity crime. If it takes longer to break in and burglars are more likely to be spotted, fewer people will try — and fewer will succeed. One nugget from the paper: The average age of burglars increased as younger people found it harder to do.

Second, stealing stuff got a lot less lucrative — and a lot more traceable. In 1990, a burglar who found a stack of home electronics could convert it to cash pretty quickly. Today, a lot of our most valuable consumer tech is easy to disable from a distance and track. Sometimes the math doesn’t add up: Stolen tech often isn’t worth that much on the resale market because products have gotten cheaper. One plus of living in a richer society — which America very much is compared to 1990 — is that the wages of crime pay less comparatively.

At the same time, there’s the simple fact that people carry — both on themselves and at home — far less paper cash than they used to. For any would-be mugger, the expected take is lower and the expected risk is higher. Notably, one study on Missouri linked the state’s shift from paper welfare checks to electronic benefit transfer led to a decline in crime. And that’s true in commercial operations too, as customers today are far more likely to pay with credit cards or their phone.

Third, cameras and coordination changed the game. Doorbell cameras don’t just ward off potential burglars — they provide far more specific identification if someone still tries. The same goes for ubiquitous smartphones, which enable people to instantly call for help, share a suspect’s photo, and even ping a lost device. (Good luck doing any of that in 1990 — Kevin McAllister’s land line didn’t even work!) All of this raises the perceived chance of getting caught, even if actual police clearance rates for property crimes remain very low.

Crime can still pay

Of course, all of these changes have their downside. Ubiquitous cameras can bleed into a surveillance state, one whose negative effects we’re seeing. The decline of cash reduces financial privacy and exacerbates social inequality. And the ubiquity of smartphones… well, you don’t need me to tell you the downsides of that.

It’s also true that some of what we used to think of as “property crime” didn’t vanish so much as change form. The classic late-20th-century nightmare was physical — a smashed window, a missing car, a stranger in your house. A lot of modern predation is more virtual and more bureaucratic: scams, account takeovers, and worst of all, identity fraud, which costs Americans tens of billions of dollars. And some of the “new” street-level thefts are oddly specific, like taking e-commerce packages off your stoop, something that wasn’t even conceivable in 1990.

The price tag is not small. In 2024, the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center logged $16.6 billion in reported losses, while the Postal Service estimates at least 58 million packages were stolen in 2024, adding up to as much as $16 billion in losses.

None of this negates the good news about burglaries and robberies. It just updates the definition of what “safe property” means in 2026. Maybe in the next Home Alone, the Wet Bandits will be cyberfraudsters (though at least I hope the McAllisters put an AirTag on that kid).

A version of this story originally appeared in the Good News newsletter. Sign up here!

The post The quiet revolution that made your home, car, and wallet a lot safer appeared first on Vox.