Amid a wave of high-profile killings and political violence in the United States, investigators have been confounded regularly by the absence of a recognizable agenda.

The assailants in several cases — shootings, a bombing, a planned drone attack — resisted familiar labels and categories. They were not Democrat or Republican, or Islamist militant, or antifa or white supremacist.

They were something new. In their manifestos, these attackers declared their contempt for humanity and a desire to see the collapse of civilization. Law enforcement officers and federal prosecutors have begun to describe these attacks as a contemporary strain of nihilism, an online revival of the philosophical stance that arose in the 19th century to deny the existence of moral truths and meaning in the universe.

Recent assailants who have been tagged as nihilists include the following: A 15-year-old shooter in Madison, Wisconsin, who left behind a manifesto titled “War Against Humanity” in which she described the human race as “filth.” A 24-year-old man who plotted a drone attack to blow up the Nashville power grid was seeking to precipitate “the start of the end … for the interconnected or otherwise globalized world.” A self-described “anti-natalist,” 25-year-old Guy Edward Bartkus, blew himself up outside an in vitro fertilization clinic in May, having argued that humans should not be brought into existence without their consent.

“Basically it comes down to: I’m angry that I exist and that nobody got my consent to bring me here,” the clinic bomber said in a recording posted online. “There’s no way you can get consent to bring someone here, so don’t f—ing do it.”

By March, federal prosecutors had adopted the rubric, too, coining a new official term for a variety of this destruction: nihilistic violent extremism, which they defined as “criminal conduct … in furtherance of political, social, religious goals that derive primarily from a hatred of society at large and a desire to bring about its collapse by sowing indiscriminate chaos, destruction, and social instability.” The first known use of the term came in the prosecution of a Wisconsin teenager who murdered his parents in February 2025 as part of a plot to foment a civil war and assassinate public figures.

While the hatred of these attackers sometimes veered into racist views, what stood out to investigators was the broader desire to attack all of society.

“We were seeing a set of cases in which the existing definitions did not apply,” said Cody Zoschak, a researcher with the Institute for Strategic Dialogue and former New York Police Department counterterrorism analyst who also worked on counterterrorism policy at the State Department.

Over the past 18 months, the United States has experienced a wave of high-profile targeted violence, including school attacks, a handful of bombings, and the assassinations of a Minnesota state legislator, the head of UnitedHealthcare and conservative activist Charlie Kirk. While the targets were varied, the alleged assailants all claimed to be committed to furthering a cause.

To better understand the phenomenon, The Washington Post analyzed incidents in which the perpetrator or perpetrators left written explanations of their motives, according to investigators. From a search of academic databases and news clips, 17 attacks fit the bill in the period from July 2024 — when the first assassination attempt was made on Donald Trump — to December 2025.

Several of the attacks were “political” in the conventional sense, aimed at either Democrats or Republicans or motivated by anger at the Israel-Gaza war, particularly the treatment of Palestinians. But six of those assailants fit something like the nihilistic pattern, while three others were motivated by a narrowly focused grievance that had rarely popped up before.

The “special interest” attackers include Luigi Mangione, who is charged with gunning down a UnitedHealthcare chief executive in Manhattan in December 2024 because of his anger at the industry; Army Green Beret Matthew Livelsberger, who blew up his Tesla Cybertruck in front of a Las Vegas casino in January 2025, citing the loss of U.S. military lives in Afghanistan; and Shane Tamura, who attacked a Manhattan office building in July over the National Football League’s handling of concussions.

The attacks transformed individuals’ sense of outrage into national spectacles.

Nihilists are different. In past decades, people holding solitary grievances against society may have struggled to act on them. But the internet has provided them easily accessible technical expertise and, despite their distaste for society, a sense of community. The IVF clinic bomber queried an AI application for information about the “detonation velocity” he could create with a certain type of chemical. The Nashville plotter seeking to sow chaos by blowing up the city’s power grid allegedly found information on YouTube about how to build a drone to carry explosives. They found places online to share their anger with the like-minded.

“There was a time when terrorist activity was organizational in nature. It was structured: bomb maker, recruiter, foot soldier, leader,” said Michael Jensen, the director of research for the Polarization and Extremism Research and Innovation Lab at American University. “The advent of the internet chipped away at that pretty quickly.”

Jensen added, “What is scary now is we don’t know where the next threat might be coming from.”

It was a kind of societal disorder that Shon Barnes, as police chief of Madison, Wisconsin, hoped he would never have to confront.

The puzzle

Natalie Rupnow had just turned 15. She wore glasses, had light blond hair and was small for her age. She stood 4 feet 5 inches tall and weighed 90 pounds. On the morning of Dec. 16, 2024, she entered her school in Madison, Abundant Life Christian School, carrying a used Glock 9mm handgun for which she had paid $499 three months earlier. She opened fire in a study hall, getting off 20 rounds. She did not speak and had a “calm and angry” face during the gunshots, a student witness told police. She killed two people, a teacher and a student, and injured six others. Then she turned the gun on herself.

Initially, investigators from the Madison police struggled to make sense of her motives. Some news accounts highlighted the racist slurs and Nazi imagery she had shared online. These suggested her actions were driven by antisemitic or white supremacist beliefs.

But the target of her attack — a predominantly White Christian school — didn’t fit that explanation.

In the days after the shooting, news outlets sought ways to explain what might have led Rupnow to this level of violence. She had been depressed, some said, possibly bullied at school and upset after her parents divorced each other for the second time in 2020. She had been in therapy. She lived with her father, Jeffrey Rupnow, who drove a recycling truck. She stayed some weekends with her mother, Mellissa Rupnow, who was an apartment property manager.

Barnes, then the chief of police, had to face residents and the news media demanding an answer: Why did she do it? He was not alone in struggling to understand her motive.

“When innocent people are killed, people want some idea of why it happened,” he said.

What the initial news accounts missed is that more than two years before the shooting, Natalie Rupnow had fallen for the shadowy snares of the internet.

In June 2022, Rupnow had created a profile on a “friend-making” app for young people known as Swipr and listed her age as 17. She was just 12, though, and in seventh grade. Through Swipr and Snapchat, she had come into contact with a man from Illinois who sent her a number of lewd texts. The man said he was 17 and one day arranged to visit her at her home when her father was at work. He then took her to a Best Western hotel room. The man was actually 22. Police charged him with child enticement, according to court documents.

Rupnow’s online activity continued, and within 18 months, she was planning the attack on Abundant Life.

Search for a motive

After Rupnow shot up Abundant Life, with the public and the news media clamoring for an understanding, investigators traced her online activities, spoke with friends and teachers, and, in her bedroom, discovered her six-page manifesto.

Rupnow had an account on an online forum that hosts images of people dying violently. Fans on such websites are classified by researchers as part of the “true crime community” — a nonideological online subculture where fascination with mass killers sometimes stretches into admiration. Among some fans, the instigators of the attacks are viewed as romantic loners, outcasts who turn to violence in revenge against society.

In her manifesto, Rupnow professed reverence for several mass killers, describing them in language that read like the musings of a teenage fan. Like others in this world, she referred to these killers as “saints” and venerated them for their seemingly meaningless acts of violence.

“I’ve looked into him since late 2021-2022, and i’ve just realized how much potential bombs have,” she wrote of an 18-year-old who in 2018 killed 20 and injured another 70 in a bomb and gun attack at his college in Crimea. “… Some of his fan girls are like, really strange though in my opinion, but aren’t like all fangirls?”

Of a Turkish 18-year-old who stabbed five people at a mosque and broadcast the attack on social media in 2024, she wrote, “An Ultimate Saint … A being of true nature … Someone I was inspired by, maybe I didn’t know him, but what stops me, what would have stopped him from doing what was right and now proven to be a true form of being and of simple hope.”

Elsewhere, she had posted a picture of herself wearing a T-shirt bearing the logo of KMFDM, the German industrial band favored by the two teenagers who carried out the mass shooting at Columbine High School in Colorado in 1999.

“Search engines often give people a community of the like-minded — in things good and things bad,” said Barnes, the former Madison police chief.

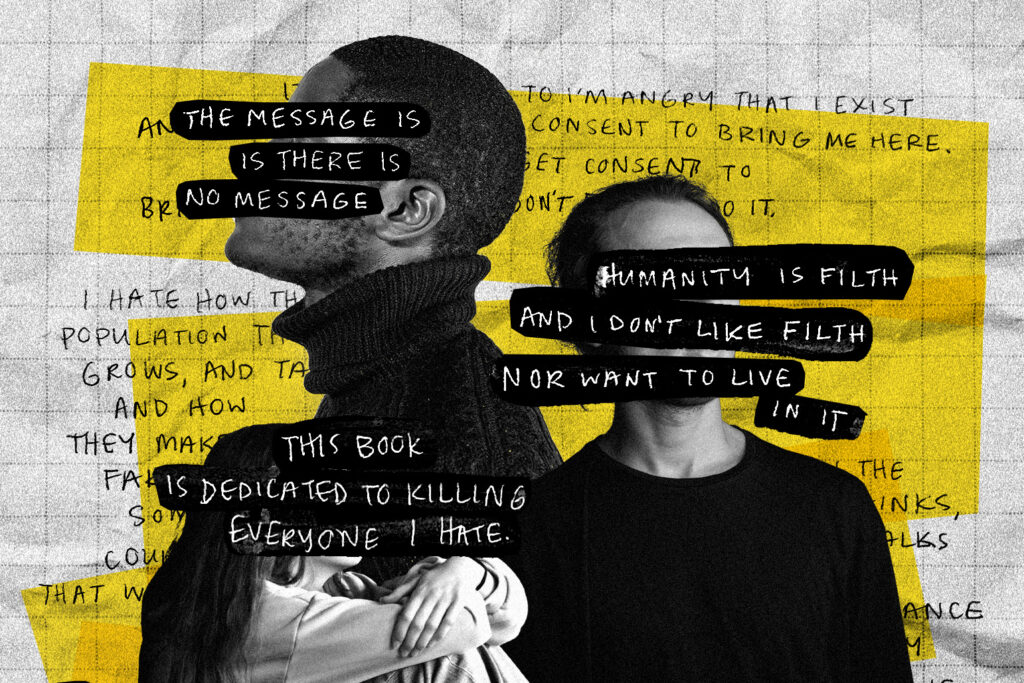

Her manifesto, “War Against Humanity,” reflected her contempt for people.

“Humanity is filth and I don’t like filth nor want to live in it …” she wrote. “This situation and the situation of a lifetime is a get the f— out moment and don’t come back, I will never go back and nag my way through life. It’s not even my fault though, it’s everyone else’s, it has to be theirs and not mine.

“ … I hate how the population thinks, grows, and talks and how they make romance fake. If only some days we could do a public execution, that would be gladly needed. I wouldn’t mind throwing some stones at idiots or even watching from the far back when they get hanged.”

As extreme as those sentiments seem, they were not necessarily original. Rupnow seemed to be following in others’ footsteps.

“A writing similar to that was discovered on someone else’s social media,” Barnes said. “There were several other writings that were similar on the web.”

Police also found in Rupnow’s bedroom a map of the school, as well as a cardboard model depicting it. Her planning appeared to be meticulous. They also found a camcorder that held footage of her posing with a gun. Rupnow aspired to be just as well-known as some of the “saints” she revered.

“You will see us on the news,” she says in one recording made in her kitchen. “You will see us everywhere.”

“I’m [Natalie Rupnow] and you will know me in a couple of years as one of your sick f—s,” she says in another.

Her father said he was unaware that she had such violent intentions.

“As you know, parenting you learn as you go. There’s no manual,” he told police. “You are flying by the seat of your pants and making the best decisions for you and your child.”

A string of imitators

Rupnow’s “kill count,” as it is referred to on the websites she visited, was lower than those of the mass shooters she idolized. But within the world of aspiring mass shooters, the petite teenager would prove remarkably influential.

Five weeks after Rupnow shot up her school, 17-year-old Solomon Henderson opened fire in the cafeteria of his school in Antioch, Tennessee, killing one student and injuring another before killing himself.

Henderson’s online writings were more obviously bigoted than Rupnow’s, laced with anti-Black and antisemitic remarks. Yet researchers say his motivations, like hers, stemmed less from ideology or any particular hatred than from a violent offshoot of the true crime community.

Like Rupnow, Henderson had an account on the online forum that hosts images of people dying violently. In his online postings he referred to her as “a saint.”

While Henderson, who was Black, criticized Black people, using slurs for them, he also used slurs for Asians and Whites. His hatred was broader than any single group.

“I can’t be a white supremacist,” he wrote.

As for targets, he shot a White girl of Hispanic descent and another male student whose name and race have not been disclosed.

“This book is dedicated to killing everyone I hate,” his manifesto concluded. “Death to all.”

Three months after Henderson’s shooting, police in Florida arrested 22-year-old Damien Allen of Loxahatchee, who had been in contact with Rupnow before her attack. Investigators said Allen was plotting seven separate mass shootings, and charged him with making written threats to kill and to do bodily harm.

Before Rupnow’s shooting, she and Allen had the following text exchange:

Allen: “We go down together.”

Rupnow: “Correct.”

Rupnow: “I love you.”

Allen: “I love you more.”

Another Rupnow fan struck just months later, on Sept. 10. A 16-year-old student opened fire at Evergreen High School in Colorado, injuring two fellow students before taking his own life. He, too, consumed violent content and, on TikTok, posted a photo of Rupnow with one of himself in a similar pose, according to researchers at the Global Project Against Hate and Extremism, which obtained archives of his social media.

But it was yet another follower of Rupnow whose words captured what may be the defining emptiness of this new wave.

In August, Robin Westman killed two children at a Minneapolis church and then died by suicide; one of his guns was inscribed with the word “Rupnow.”

“This is not a church or religion attack …,” Westman had written in his journal. “The message is there is no message.”

Aiming for societal collapse

One of the first known uses of the nihilist label by federal prosecutors came in March in the case of Nikita Casap, the Wisconsin 17-year-old who, according to federal court documents, killed his parents to “obtain the financial means and autonomy necessary” to kill President Donald Trump and overthrow the U.S. government.

Federal prosecutors filed excerpts from what they say is Casap’s manifesto, titled “Accelerate the Collapse,” linking him to nihilistic violent extremism.

“By getting rid of the president and perhaps the vice president, that is guaranteed to bring in some chaos,” according to the manifesto. “And not only that, but it will further bring into the public the idea that assassination and accelerating the collapse are possible things to do. … It is time that we lead the way to the System collapse.”

Casap considered himself an “accelerationist,” a label for those who believe that society is irreparable and that the only solution is its destruction, after which it can be rebuilt, according to court documents. Skyler Philippi, the 24-year-old who plotted to blow up a Nashville power grid, was also allegedly seeking society’s collapse. In his manifesto, as quoted by federal agents, Philippi wrote: “When the start of the end comes for the interconnected or otherwise globalized world, what will reflect and appeal [to] those seeking safety will be what Aryan warlords and Aryan tribes can offer.”

With the accelerationists, though, the nihilistic classification can be a matter of dispute. Many accelerationists also seem to overlap with hate groups and express hatred toward Jews, African Americans and other minority groups.

Lumping them in with the nihilists may too easily overlook these historical hatreds, said Wendy Via, co-founder and chief executive of the Global Project Against Hate and Extremism. The term could reflect the priorities of the Trump administration, which has pulled back on research into hate groups. A prominent University of Maryland dataset that tracked hate crimes and terrorist attacks, for example, has been scuttled.

“We shouldn’t just lump everything into this new category,” Via said, adding that nihilistic violent extremism is more an evolving framework than a precise definition. “If we want to solve the problem, identifying the motivation correctly is important.”

Some of the recent violence, nihilistic or not, may be traced to the nation’s increasingly aggressive political arguments, she said.

“People hear the rhetoric and think of violence as a solution,” Via said.

Barnes, the former Madison police chief, also traces the roots of the alienation of some young killers to the rage visible in society at large.

“What this kind of behavior is called, what it’s referred to, I will leave up to the FBI,” Barnes said. “But what example are we setting when leaders at the highest levels act in ways that do not suggest unity or peaceful resolution or compromise? Our children are watching. When we have this at the highest levels, how are we going to address these issues of ‘I hate everyone’?”

Ellie Silverman and Razzan Nakhlawi contributed to this report.

The post Killers without a cause: The rise in nihilistic violent extremism appeared first on Washington Post.