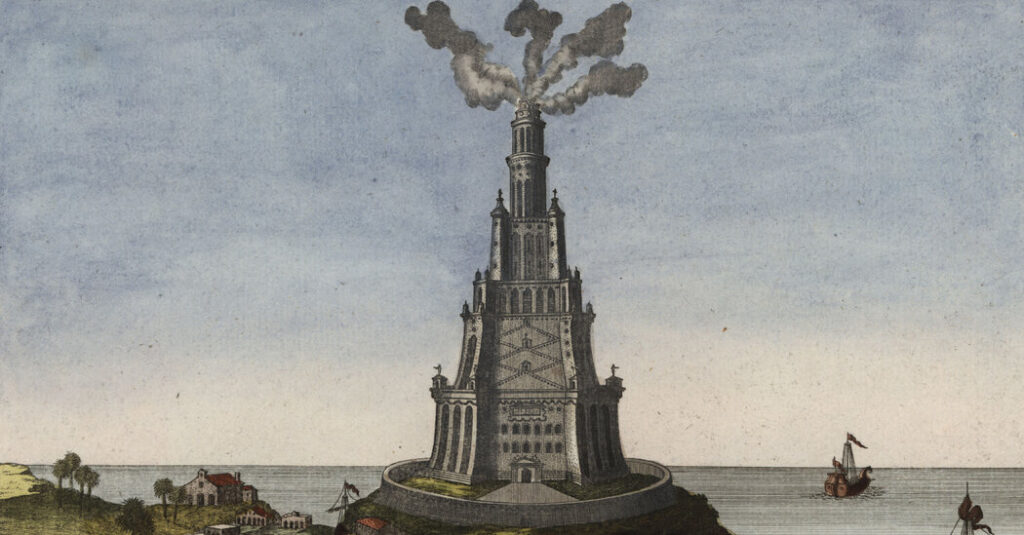

Towering over Alexandria, the vibrant Mediterranean port and capital of Ptolemaic Egypt, an enormous lighthouse was a symbol of the ambition of the Hellenistic age, a 460-foot skyscraper of granite and limestone that Greeks of the second century B.C. deemed the seventh wonder of the ancient world. Its powerful beam was a nightly promise of safety for mariners approaching the treacherous coastline, and the structure was second in height only to the Great Pyramid of Giza, the first wonder of the world and the only one that survives.

For nearly 1,600 years, the lighthouse, known as the Pharos of Alexandria, stood on an island at the entrance to the city’s eastern harbor as a sentinel defiant against time and nature, shrugging off dozens of earthquakes. But even monumental ingenuity has its limits; in A.D. 1303, a doozy of a tremor caused a tsunami so intense that it left the structure in shambles. Another quake, 20 years later, brought the rest crashing down, a tumble of statues and masonry eventually swallowed by the ever-rising sea.

“The architectural fragments lie scattered over 18 acres underwater,” said Isabelle Hairy, an archaeologist at the National Center for Scientific Research in France and the Center for Alexandrian Studies in Egypt. “The visibility is extremely bad, the seabed is uneven and there are no clear layers of sediment.”

For the last four years, Dr. Hairy has led the Pharos Project, guiding an elite squad of historians, numismatists, architects and graphics programmers to reconstruct the ancient lighthouse as a comprehensive digital twin. Having so far analyzed roughly 5,000 blocks and artifacts on the sea bottom, the team is reverse-engineering the ancient structure from its 14th-century collapse.

This ambitious fusion of antiquity and innovation relies on photogrammetry, which stitches together thousands of two-dimensional images to create precise three-dimensional models, effectively assembling a colossal archaeological puzzle piece by virtual piece.

“The project has enduring importance and interest globally, both for the underwater archaeology aspect and for the nature of the finds — including the 80-ton blocks,” said Paul Cartledge, a historian of Greek culture at the University of Cambridge who is not connected to the operation. “Try dredging those by hand. Not recommended.”

A projection of power

The story of the Pharos began with a general’s loyalty to a fallen king. After Alexander the Great, a ruler of Macedonia and its vast empire, died suddenly in 323 B.C., his boyhood companion Ptolemy took control of Egypt as its governor. In 305 B.C., he appointed himself pharaoh, Ptolemy I Soter (the Savior).

To transform the city into the center of the cult of Alexander the man-god, Ptolemy commissioned a monumental lighthouse. In the book “The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World,” Bettany Hughes, an English historian, writes, “The Pharos had a double purpose: both practical — its role as a lighthouse — and ideological, as an emblem of association with Alexander and his one-world vision.”

While Ptolemy I probably lived to see the first stones laid near the time of his own death, around 282 B.C., it was his son and successor, Ptolemy II Philadelphus, who saw the project through. Construction took 15 years and coincided with a whirlwind of palace intrigue, as the slightly distracted Ptolemy II exiled his first wife and co-ruler, Arsinoe I, and married his sister, Arsinoe II. Architecture takes time; family drama takes precedence.

Despite limited physical evidence and clashing historical accounts, scholars generally agree that the Pharos was a majestic three-tiered tower resembling a wedding cake. The square base, sprawling over 1,115 feet, served as a fortified hub for fuel and livestock, housing a garrison and apparatuses for lifting food and supplies.

Rising from its immense foundation, the structure narrowed into a graceful, eight-sided marvel punctured by open windows and crisscrossed by internal spiral stairs. This octagonal heart, stretching nearly 200 feet into the sky, was the work of Sostratus of Cnidus, a visionary builder from what is now southwestern Turkey. By shaping the second story as an octagon, he honored the eight winds of the sea.

The signaling lantern burned in the crowning, circular tier, probably in an open-air setup exposed to the Mediterranean winds rather than encased in glass. Above it all, a grand 50-foot statue of a god, widely believed to be Zeus, watched over the port. Some authorities interpret this top section differently: Perhaps it was a fourth, subdivided layer that housed the beacon and statue pedestal separately.

More than just a functional navigational aid, the Pharos stood as a dazzling projection of Ptolemaic power, engineered to be seen for some 37 miles across the Mediterranean. This intense light is believed to have been achieved through a sophisticated combination of roaring fires — most likely fueled by oil, given Egypt’s sparse timber resources — and beaten-copper mirrors designed to focus the beam.

Andrew Michael Chugg, an independent historian and author of “The Pharos Lighthouse in Alexandria,” has proposed that the light was produced by an oil lamp inside a largely transparent glass sphere. Such a device, he argued, probably would have been open at the top, allowing it to function like a contemporary hurricane lantern, protecting the flame while enhancing its brightness and direction.

So bright was the lighthouse’s watch fire, the Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder observed, that it risked being mistaken for a star.

Resurfacing relics

Reduced to a shell by the 1323 earthquake, the lighthouse lay neglected until 1480, when Sultan Qaitbay repurposed its ruins to build a citadel that still guards the shore. The lighthouse found a second life in this fortress, but much of ancient Alexandria — including the royal palace and Alexander the Great’s tomb — sank beneath the waves as a result of geological shifts.

Hints of this sunken kingdom surfaced in 1916 when reports of underwater statues began to emerge. Following a brief UNESCO scouting mission in 1968, the site was finally brought to light in 1994 through the mapping efforts of the French archaeologist Jean-Yves Empereur and his team from the Center for Alexandrian Studies.

Eighty-five feet down, divers discovered a stunning trove of artifacts, including 25 sphinxes, a 70-ton door frame, another door frame 16 feet high and elegant columns from the reign of Ramses II in the 13th century B.C.

The most striking find was a weathered statue of a Ptolemaic queen in the guise of the goddess Isis, originally 40 feet tall, alongside either a god or her pharaoh. Dr. Hughes wrote, “Given the fluid nature of identification and association between divine heroes and humans, most likely these Pharos sculptures were an alchemy of both royal rulers and mythological beings.”

Last summer, working with the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, the team used a barge-mounted, high-capacity crane to hoist 22 granite blocks, some weighing up to 80 tons, from the seafloor.

The operation recovered more than 100 submerged relics, including lintels, foundational paving stones, lead clamps and uprights from the gargantuan entrance. Notably, the haul included remnants of a previously unrecorded pylon, featuring a doorway that seamlessly blended Egyptian stylistic elements with Greek construction know-how.

Once safely brought to the surface, these colossal components underwent high-resolution scanning by engineers from La Fondation Dassault Systèmes, which documented and virtually repositioned them to reimagine the Pharos’s lost design without putting the original stone at risk. After the blocks were measured, they were returned to the sea for long-term preservation.

A new view on old assumptions

Many experts remarked that the PHAROS Project had significantly advanced the modern understanding of the lighthouse by moving from speculative sketches to empirical, physical analysis.

Among other insights, the recovery has revealed that the structure was assembled using advanced interlocking techniques rather than relying solely on mortar. “The clamps help explain how such a massive structure was erected in such a short time,” Dr. Hairy said.

The finds confirm that large blocks of local limestone were used for the core and granite for the structural doorway, which helped the building withstand centuries of environmental stress. The jambs and lintels have allowed researchers to map the precise entrance of the lighthouse, changing previous assumptions about its scale.

Among other surprises, the research indicated that the lighthouse deteriorated gradually rather than abruptly, a conclusion reached after identifying five ancient sea levels, with the lowest one 25 feet below today’s.

Dr. Hairy estimated that the Pharos Project was still generations from completion, hampered by minimal state funding and worsening pollution. As garbage and rising silt cloud the water, stalling photogrammetry and recovery, future missions must revert to basic lifting, using heavy-duty inflatable bags to raise submerged blocks.

But the mission has already defied expectations. According to Dr. Cartledge, the team has proved the unthinkable: The lighthouse truly was as prodigious as ancient chronicles claimed, outlasting the skeptics who long dismissed those accounts as mere Ptolemaic flattery.

The post Rebuilding the Lighthouse of Alexandria, Block by Virtual Block appeared first on New York Times.