The C.I.A.’s World Factbook, a repository of facts on nations from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe that for six decades provided detailed figures on birth and death rates and major exports, relied upon first by government agents and eventually researchers, educators, journalists and more, was shuttered without warning on Wednesday.

The sudden closure of the Factbook’s website, with all of its entries no longer available to the public, left Jay Zagorsky’s business students at Boston University in the lurch midway through an exam due at midnight the next day.

His exams are regularly open-Factbook, and two questions relied on its famously tidy tables of economic certainty. In an instant, a trusted companion of lectures and late-night problem sets was gone.

“That was a great joy this afternoon,” Mr. Zagorsky said in an interview on Wednesday evening, recalling the moment faculty colleagues had begun talking to one another in disbelief. “Oh my god. What do we do? The Factbook just went offline? How do we let them finish the answers on the exams?”

For more than six decades, the Factbook served as a free public reference guide, first in print and then eventually online, offering regularly updated data on economics, populations, government and geography. The Factbook, published by the world’s premier spy agency, was long considered an objective source in an increasingly subjective information ecosystem.

The C.I.A. declined to say why it was ending the Factbook. But the disappearance feels personal to those who relied on it, not because it was exciting, but because it was steady.

It was so trustworthy that it earned its own “Jeopardy!” category in 2020.

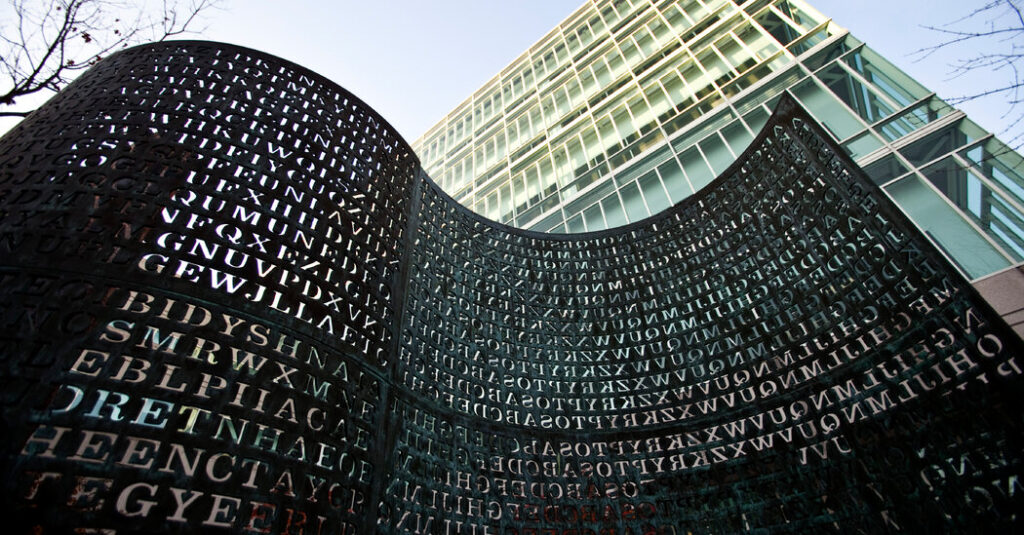

First published in 1962, during the height of the Cold War, the collection of global facts was classified and known as The National Basic Intelligence Factbook.

By 1971, a companion unclassified version appeared. A decade later, it was given a simpler name, The World Factbook. And in 1997, at the dawn of the internet era, it went online, available not just to federal operatives but to anyone with an internet connection and a question.

The books themselves are hundreds of pages long with front covers illustrated by world designs including a compass and a world map, and inside among the densely packed facts and figures are intricate maps. Some are so large they must be unfolded carefully, and they are attractive enough to be hung up for reference at a glance.

Did you know the arctic fox starts shivering only once it reaches minus-94 degrees Fahrenheit? Or that the world’s oldest continuously functioning clock is in Prague? The Factbook did.

Its website featured a “fact of the day,” including a wide range of topics, like volcanoes, poinsettias, the origin of the name Antarctica and other tidbits.

Yet, not everyone is sad to see the Factbook gone.

Beth Sanner, a former senior government intelligence official, recalled working with other analysts to put the Factbook together in the 1980s. Back then, analysts were given the tasks of writing and reviewing paragraphs, population figures and political party names, she said.

The work was boring. Also risky, she said. Get someone wrong or make a spelling error, and the complaints roll in. When the Factbook started, the work gave people access to information compiled by a trusted source.

“When it started, it was important, because there was no such thing as the internet,” she said. “Now it’s like, what’s the point?”

The Factbook, over time, became something of a box-checking exercise, she said. Eventually, contractors took it over. It persisted less because it was useful but rather because it had always existed and no one wanted to kill it.

“C.I.A. is not the Library of Congress,” Ms. Sanner said with a laugh. “The intelligence community shouldn’t be your librarian.”

But for the many more who will miss it, the legacy the Factbook leaves behind is the idea that understanding begins with careful observation, shared openly.

“Though the World Factbook is gone, in the spirit of its global reach and legacy, we hope you will stay curious about the world and find ways to explore it … in person or virtually,” the C.I.A. said in a post on its website announcing the Factbook’s end.

John Motyka contributed research.

Rylee Kirk reports on breaking news, trending topics and major developing stories for The Times.

The post C.I.A. World Factbook Ends Publication After 6 Decades appeared first on New York Times.