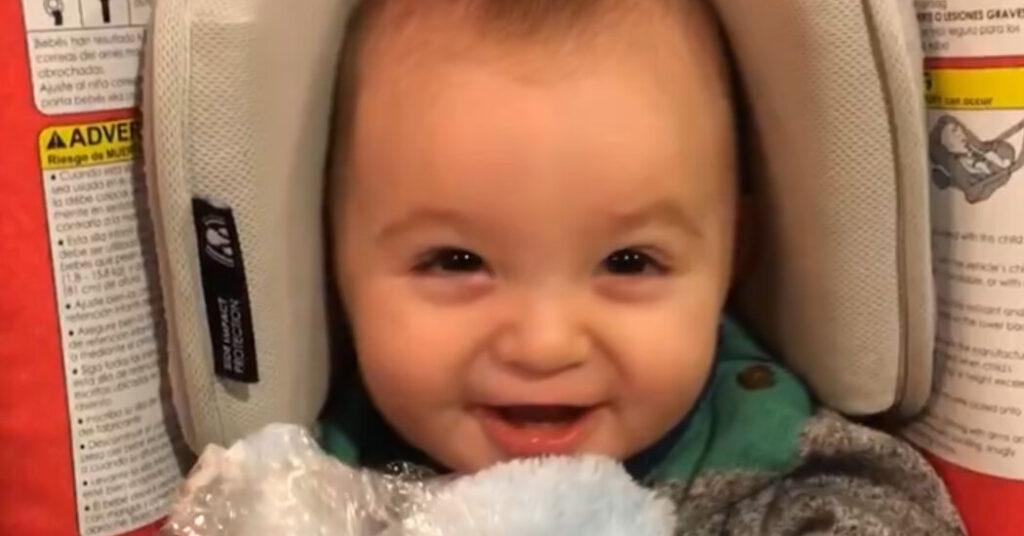

My son was 14 weeks old when he made his first unmistakable whole-body belly laugh. In the months that followed, his laughter was accompanied by playful provocations — grabbing my hair and shrieking with delight, blowing mouthfuls of mashed bananas skyward and squealing when they landed on the floor. These incidents signaled something more than laughter: An early sense of humor was emerging, initiated by him, months before the other milestones that parents await in the first year.

For me as a mother, this was delightful, but as a developmental psychologist, I was perplexed. Despite my Ph.D., I’d never come across research on infant laughter or humor. While psychologists and parenting experts had extensively researched early skills like walking, language and attachment, humor was largely neglected as if too frivolous for scientific attention.

But those early laughs inspired me to study baby humor full time. In the ensuing two decades, my own research, along with that of the few others chasing this phenomenon, shows that laughter and humor are fundamental to how babies learn about and participate in the world. In an age of parental anxiety, humor and laughter are also among the most joyful developmental milestones.

In the video below, three babies, all between the ages of 2 and 4 months, share their first belly laughs.

Look at how intensely the babies’ gazes are fixed on their parents, regardless of the specific tactic the parents use to amuse them. In the 1870s, Charles Darwin described his own infant son’s first display of what he called “incipient laughter,” and hypothesized that laughter serves an evolutionary function, reinforcing social bonds without requiring language.

Indeed, this idea — that laughter is primarily social, less about comedy and more about connection — holds true for adults as well, and has been underscored by research showing that laughter overwhelmingly occurs in the company of others and typically follows banal remarks in conversation, rather than in response to jokes or punchlines.

The signature belly laughs seen in the video above are involuntary, bursting forth during genuine, uncontrollable amusement. This type of laughter is driven by the brain’s limbic system, structures crucial for emotion, memory and motivation. But by 6 months, our lab has found, infants can intentionally produce a laugh. This ability comes not from the limbic system but from the brain’s language areas and emerges at the same time as babbling. Six-month-olds will deploy laughter to prolong a game of peekaboo or to signal a desire to join in.

But laughter does more than increase pleasurable social contact; infant laughter, especially when it occurs in response to humor, signals a cognitive achievement. When an infant laughs at Dad wearing a spoon as a mustache, it reveals the baby’s knowledge about spoons and mustaches, as well as about the person wearing it.

Even before her first birthday, the 8-month-old girl in the video below recognizes a “benign incongruity” — an unexpected yet harmless event — that does not align with her typical experience, in this case a stuffed toy repeatedly taking flight from atop her mother’s head. The surprise effect of squeezing Bubble Wrap becomes increasingly funny to a 7-month-old, while a toy popping out of a box delights a 9-month-old so much he falls over from laughing.

Yet, beyond recognizing the incongruity, perceiving it as funny requires babies to resolve or make sense of it, by either anticipating or identifying the cause of these unusually strange experiences. In verbal jokes, incongruity resolution occurs the moment the punchline makes sense, which is often marked by laughter. Although psychologists have known that adults and children use incongruity resolution to perceive humor, scientists largely ignored it in infants, dismissing them as cognitively immature.

Recently, our lab showed 6-month-olds highly incongruous events — magic tricks in which objects, manipulated by a hidden magician, inexplicably disappeared or defied gravity. Research shows such events captivate infants, provoking intense staring. We discovered that infants seemed able to make sense of these events when we altered one simple condition: having the magician be visible. How do we know? Because they laughed.

Generally, it’s been assumed that infants mimic the humor of those in their social orbit. If that were the case, however, babies would be limited to producing what they’d previously seen, unable to create the original “jokes” parents frequently report. Around 6 months infants begin intentionally creating humor using “clowning” — making silly faces, gestures or sounds, misusing objects, or mimicking others for a laugh.

Such jokes get increasingly elaborate as babies get older. The babies in the videos below are masters of clowning. One makes strange sounds by blowing through plastic to amuse his twin; another pops out of a bin meant for recycling; a clever 18-month-old pretends to “poo” in her highchair while her parents laugh in faux horror. Notice that in each example, the babies use a typical behavior to playfully violate some pattern of social life in a way that others recognize as absurd, demonstrating infants’ early capacity to perceive and create playful incongruities — nonverbal jokes — to meaningfully engage with others.

My colleague Vasudevi Reddy, a mother and developmental scientist herself, observed her 11-month-old daughter’s penchant for teasing family members — and then laughing at her own antics. Dr. Reddy inferred that the ability to tease reveals infants’ insight into others’ minds and how to provoke them. Teasing requires knowing how to engage another person in a safe, playful interaction, including how and how much to push a set boundary.

In the video below, a 14-month-old boy offers food to his dad, then suddenly reneges, feeding himself instead to entertain his laughing parents. A 9-month-old deliberately approaches a playfully forbidden plant. A 10-month-old continues to reach for the forbidden cat food bowl in full sight of his grandmother who playfully prohibits him with “uh-uh-uh,” an utterance he has also added to the game.

In each example, notice the baby checking with the adult before carrying out the prohibited act, their eyebrows raised as if asking, “But if I do, what will you do?” Their smiling signals they are engaging their play partner with a conscious violation, as though the playfulness is less about the cat food or plant, for example, than the other person’s reaction.

That these cognitive skills — incongruity resolution and insight into others’ minds involved in teasing — appear before a child’s first birthday and before other major milestones like walking or talking, suggests that nature preserved, if not prioritized, laughter and humor in the service of development.

Babies’ laughter, especially in response to surprising or absurd events, reflects their curiosity, understanding and drive to connect with the people in their lives. Nature has built in laughter — and its close cousin, humor — as an intrinsic part of early development. Although walking and talking tend to steal the show, simply laughing with your baby is just as important, if not even more fun. Humor may be cognitively complex, but sharing in it together is as easy as child’s play.

Gina Mireault is a developmental psychologist at Vermont State University. Video production and editing by Emily Holzknecht.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.