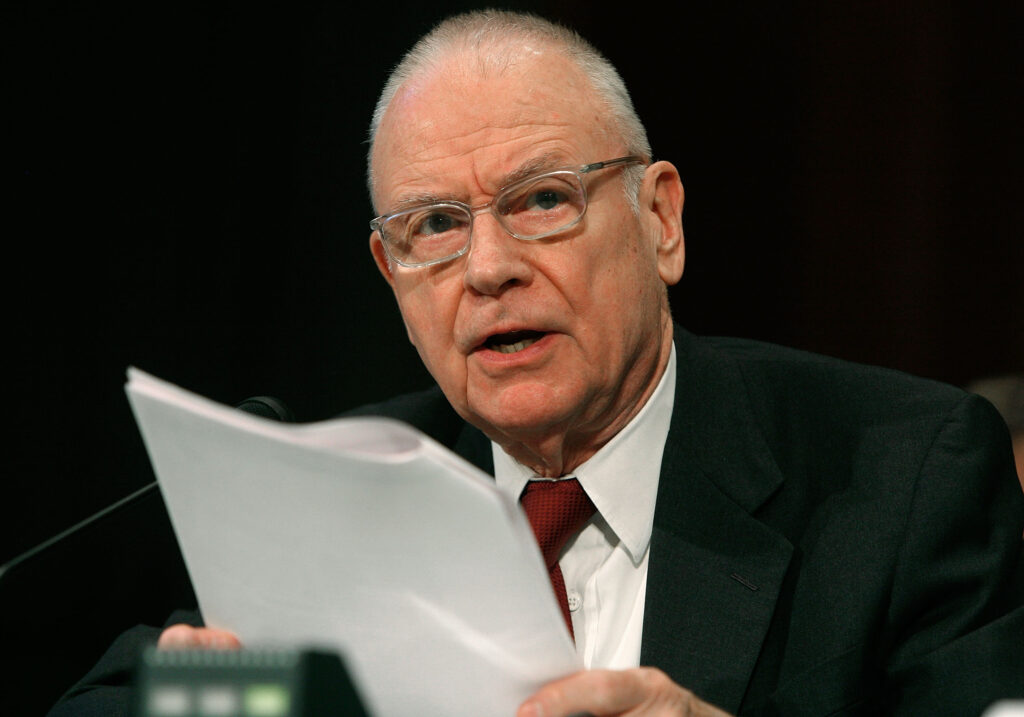

Lee H. Hamilton, a deliberative, soft-spoken Indiana Democrat who won bipartisan respect for his integrity and foreign policy expertise during 34 years in the U.S. House of Representatives, and who later helped steer high-profile inquiries into the 9/11 terrorist attacks and Iraq War strategy, has died. He was 94.

His death was announced Wednesday by Indiana University, where he taught in recent years. The school did not say when or where he died.

Mr. Hamilton, who was first elected to the House in 1964, became a prominent voice in some of the most contentious foreign policy debates of his era.

The son of a pacifist Methodist minister, he helped lead an unsuccessful effort in 1991 to block President George H.W. Bush’s use of the military to drive Iraq from Kuwait. During the Reagan administration, the congressman had forcefully opposed military aid for the anti-communist contra rebels fighting to overthrow Nicaragua’s left-wing Sandinista government.

An all-state Hoosier high school basketball star, he maintained the lanky build and crew cut of his youth into his senior years. He also maintained a middle-of-the-road voting record that reflected the largely rural, small-town slice of southern Indiana he represented.

He was measured in tone and language, almost professorial in manner — the antithesis of the stereotypical backslapping, lectern-thumping politician.

“Lee Hamilton is a thinker, which makes him a little different,” political commentator Chris Matthews, then an aide to Speaker Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill Jr. (D-Massachusetts), told the New York Times in 1984. “He makes his case logically, deductively. He’s not the kind of visceral politician you see around here.”

At the time, Mr. Hamilton chaired the Europe and Middle East subcommittee of the House Foreign Affairs Committee and was O’Neill’s point man in pushing the Reagan administration to withdraw U.S. peacekeepers from Lebanon after the terrorist bombing in Beirut that killed 241 American service members. He later chaired the full Foreign Affairs and Intelligence committees.

Mr. Hamilton advocated an activist role for Congress in shaping foreign policy and cautioned lawmakers against ceding all responsibility for military intervention to the president.

The proper boundary between the executive and legislative branches was at the heart of the Iran-contra affair, which raised Mr. Hamilton’s profile somewhat beyond Capitol Hill.

After disclosures that the Reagan administration had diverted profits from the secret sale of weapons to Iran to fund the Nicaraguan rebels, then-Speaker Jim Wright (D-Texas) appointed Mr. Hamilton to head a special House committee to investigate the clandestine arrangement, which was designed to circumvent Congress’s ban on funding of the contras.

In 1987, Mr. Hamilton’s committee and a Senate panel chaired by Democrat Daniel K. Inouye of Hawaii held 41 days of televised hearings. The two key players, Vice Admiral John M. Poindexter, Reagan’s national security adviser, and an aide, Lt. Col. Oliver L. North, were unrepentant when they appeared, insisting that the covert program was in the national interest.

Blaming the scandal at least in part on Congress’s “fickle, vacillating, unpredictable, on-again-off-again policy” toward the contras, North told the committees: “The Congress of the United States left soldiers in the field unsupported and vulnerable to their communist enemies. . . . I am proud of the efforts that we made, and I am proud of the fight that we fought.”

Mr. Hamilton’s reply was polite and stern. “I cannot agree,” he said, “that the end has justified these means, that the threat in Central America was so great that we had to do something even if it meant disregarding constitutional processes [and] deceiving the Congress and the American people.”

He concluded: “Democracy has its frustrations. You’ve experienced some of them, but we — you and I — know of no better system of government. And when that democratic process is subverted, we risk all that we cherish.”

In the end, the two committees found no conclusive evidence that Reagan was aware of the diversion. But their majority report concluded that laws had been disregarded and that the president “created or at least tolerated an environment where those who did know of the diversion believed with certainty that they were carrying out the President’s policies.”

North and Poindexter were later found guilty of criminal charges stemming from the Iran-contra affair, but their convictions were overturned on appeal.

In an interview for this obituary in 2016, Norman Ornstein, a political scientist at the American Enterprise Institute, called Mr. Hamilton “one of the premier legislators of his time.”

At least two Democratic presidential candidates, Michael Dukakis in 1988 and Bill Clinton in 1992, considered Mr. Hamilton as a running mate. His less-than-lively style and his record on some social issues — most noticeably, his opposition to federal funding of abortions except in cases of rape, incest or a threat to the mother’s life — may have hurt his chances.

Mr. Hamilton did not seek reelection in 1998, but his career in elective politics proved to be only a first act. The second was a run of leadership roles in public policy and academic undertakings that cemented his standing as one of Washington’s elder statesmen.

In 2002, he was named vice chairman of the 9/11 Commission, an independent, bipartisan panel created by Congress and the White House to examine the terrorist attacks a year earlier on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon.

Chaired by former New Jersey governor Thomas Kean, a Republican, the 10-member group issued a unanimous report in 2004 identifying a raft of government shortcomings that contributed to the 9/11 disaster and 41 recommendations to prevent a recurrence. The report led to a number of changes in national security policies and organization, including the creation of a new position — director of national intelligence — to unify the intelligence community.

Though the commission was not without critics, Kean and Mr. Hamilton, who worked essentially as co-chairs, got high marks for steering the investigation through a political minefield and producing a document that had the backing of all commission members, Republicans and Democrats.

Mr. Hamilton returned to the limelight in 2006 as co-chair, with former secretary of state James A. Baker III, of the Iraq Study Group, a bipartisan panel organized by the U.S. Institute of Peace to propose strategies to stabilize Iraq, where sectarian violence was taking an increasing toll in American and Iraqi lives three years after the U.S.-led invasion.

Among its 79 recommendations, the 10-member group called for boosting diplomatic efforts in the region, including engaging Syria and Iran, and increasing the number of American troops embedded in Iraqi units for training purposes while gradually decreasing the strength of U.S. combat forces.

In part because of Baker’s close connection to the Bush family, the panel’s work drew significant media attention. But in January 2007 — in what then-Vice President Dick Cheney later described as a “repudiation of the Baker-Hamilton report” — President George W. Bush announced the deployment of more than 20,000 additional U.S. troops to Iraq to provide security, mainly in Baghdad. The surge would buy time for the Iraqi government to strengthen its military capacity, the administration argued.

In 2015, President Barack Obama awarded Mr. Hamilton the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor. The White House announcement called him “one of the most influential voices on international relations and American national security over the course of his more than 40-year career.”

Lee Herbert Hamilton was born in Daytona Beach, Florida, on April 20, 1931, and as a child, he moved with his family to Evansville, Indiana, where his father had a church assignment.

He graduated in 1952 from DePauw University and completed a law degree at Indiana University in 1956. He was a lawyer in Columbus, Indiana, when he got involved in politics, and in 1964, he rode President Lyndon B. Johnson’s coattails to victory over an incumbent GOP congressman. Except for a close call in the GOP landslide of 1994, he repeatedly won reelection by comfortable margins.

His wife of 57 years, Nancy Nelson, died in a car accident in 2012. She and Mr. Hamilton had three children, Tracy Souza, Deborah Kremer and Douglas Hamilton. Information on survivors was not immediately available.

After leaving Congress, Mr. Hamilton was president for more than a decade of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington. He also directed what is now the Center on Representative Government at Indiana University in Bloomington and wrote books on Congress and international affairs.

When Mr. Hamilton left the Wilson Center in 2010 and was preparing to move back to Indiana, an NPR interviewer asked him what he had learned over his many years in public life.

“I think that you come filled with ambition and drive and energy and wanting to accomplish great things, and you find the system is very hard to move, to make it work,” Mr. Hamilton replied. “I think what has impressed me over the years is the sheer complexity and difficulty of governing this country.”

Harrison Smith contributed to this report.

The post Lee Hamilton, foreign policy leader in Congress, dies at 94 appeared first on Washington Post.