On Sunday evening, as stars walked the red carpet at the Grammy Awards, President Trump announced without warning his intention to close and renovate the Kennedy Center. His statement contained scant details, though it did mention that the venue will shut on July 4, “in honor of the 250th Anniversary of our Country,” and reopen in roughly two years—that is, while he’s still in the White House.

The president framed the closure as one urgently necessary to improve what he called a “tired, broken, and dilapidated Center”—although, notably, the venue dramatically expanded its performance space in 2019. Trump’s decision could easily be read as one of petulance or spite: Since he installed himself as the Kennedy Center’s chairman, replaced its president and some board members with ones loyal to him, and added his name to its facade, ticket sales have tanked, and enough artists canceled or turned down engagements that the theater has no 2026–27 season. Even “the President’s Own” U.S. Marine Band dropped a performance there.

[Read: Trump’s golden age of culture seems pretty sad so far]

But to understand the projected closure—even if temporary—of the Kennedy Center only in its immediate context is to ignore the larger losses that will accompany it. Last month, the composer Philip Glass called off the premiere of his new Symphony No. 15, Lincoln, which the National Symphony Orchestra commissioned six years ago, saying that “the values of the Kennedy Center today are in direct conflict with the message of the Symphony.” Glass’s comment suggests another risk to the nation’s cultural life: that the “new and spectacular Entertainment Complex” Trump promises to build out of the Kennedy Center’s steel and marble won’t represent John F. Kennedy’s cultural legacy—which is to say it will no longer stand for the value of the arts.

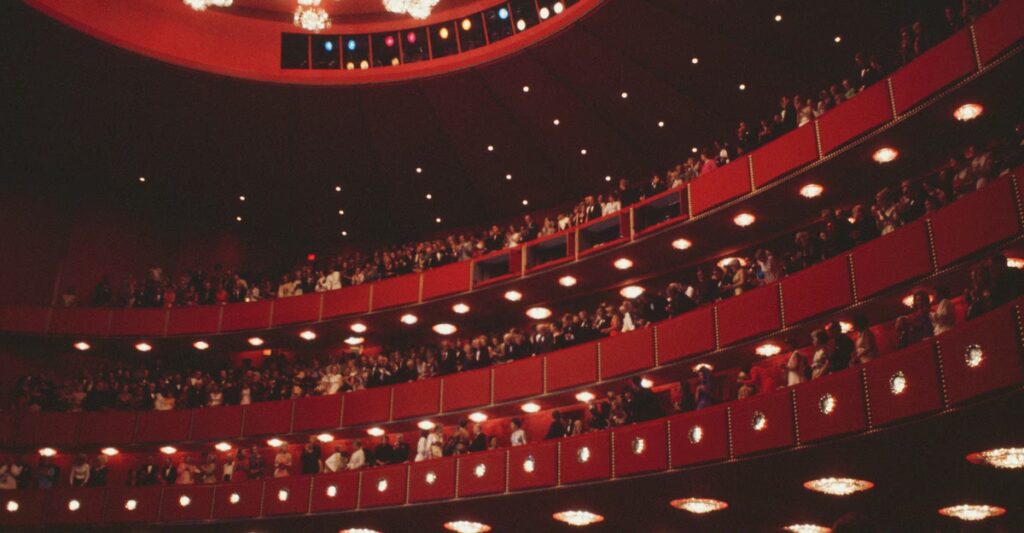

The Kennedy Center’s unanticipated absence comes with immediate, tangible consequences for both Washington, D.C., and the country’s cultural landscape. Although the Kennedy Center isn’t the most cutting-edge venue out there—if anything, many would call it stodgy—it has often operated, as The New Yorker’s Katy Waldman has written, as a “tryout theater” where shows can experiment pre-Broadway. It’s also the home and major underwriter of the National Symphony Orchestra and, until recently, the Washington National Opera, two of the largest organizations performing and commissioning new works in what Waldman describes as “endangered national art forms.” Both will surely relocate to other theaters—the opera has already found hosts for its 2027 and 2028 shows—but the precarity and disruption of not having a permanent home are inarguable.

Opera and orchestral performances are expensive to put on, and many see both as examples of what my colleague Gal Beckerman has described as John and Jacqueline Kennedy’s “patrician” taste. Sustaining them at a high level, as the Kennedy Center has done for decades, requires investment and dedication; so does building new audiences for works that can seem old-fashioned. When the Kennedy Center commissions a new composition or opera, it is also a potent reminder that these forms have life beyond Bach and Mozart, and belong to the present as well as the past.

By giving the NSO and WNO a home, the Kennedy Center also buoyed the arts life of Washington, D.C., more deeply than it does by bringing touring shows to the city. Plenty of NSO members teach their instruments on the side, and other classical musicians in the region moonlight as NSO alternates, such that a talented young cellist in D.C. might very easily end up with a teacher who has shared a stage with Yo-Yo Ma. During the orchestra’s summer recess, it performs affordable outdoor-movie play-alongs—Harry Potter with a world-class orchestra!—that are much more approachable than the debut of a Glass symphony. If the institution that made the latter possible vanishes, the former, too, may be gone.

The more significant risk is of a Kennedy Center that no longer channels its namesake’s profound and public belief that democracy and the arts are intertwined. The Kennedys invited artists, musicians, and writers to the White House. Kennedy chose the abstract expressionist painter Elaine de Kooning, rather than someone with a more traditional style, to do his presidential portrait. His speeches on and attention to culture laid the groundwork for the creation of the National Endowment for the Arts, and he agitated for the long-awaited completion of the institution that, after his death, became the Kennedy Center.

In a 1963 speech at Amherst College honoring Robert Frost, Kennedy described creating art as a form of patriotism, regardless of whether the art itself was patriotic. He argued that the “highest duty of the writer, the composer, the artist is to remain true to himself and to let the chips fall where they may. In serving his vision of the truth, the artist best serves his nation.” Trump, who sets great store by personal loyalty, seems uninterested in such an idiosyncratic and potentially eclectic vision.

Kennedy’s ideal of service—“ask not what your country can do for you”—is nowhere in Trump’s second White House. The same holds for Kennedy’s elevated concept of creative duty. Many of Trump’s grievances with the Kennedy Center, as with the Smithsonian, seem aimed at narrowing rather than expanding its artistic capabilities, limiting it to “classical, patriotic, and family-friendly art.” Such demands run directly against the ideal of art emerging from the artist’s inner self, transmitting individual experience rather than serving external mores.

[Read: The real fight for the Smithsonian]

Beyond his programming notes, Trump and the Kennedy Center’s new director, Richard Grenell, reportedly also want it to make more money. Trump has repeatedly claimed that it has been in bad financial condition for years, which its former director disputes. Asking the closest thing the country has to a national theater to concentrate on its earnings endangers any art form with a small audience, while also curtailing ways that such an audience might grow. Consider the current White House’s approach to funding literature: In 2025, the NEA revoked 41 grants it had issued to magazines and small presses, explaining its pivot in standardized terminations that described these organizations’ work as outside the administration’s priorities. Many of these journals and publishers focus on poetry, experimental writing, and literary translation, all precarious forms in need of support.

A country that does not value these sorts of writing is the same as one that does not value opera. It’s a country that doesn’t ask or expect its art to reach out to new audiences or transgress its traditional boundaries, let alone probe visions of the truth that might have little to do with accepted narratives. In order to do any of these things and get their work into the public eye, artists need the stability and support that organizations of all sizes, whether a small poetry journal or the Kennedy Center, offer. Without them, cultural life would narrow philosophically—a shrinkage that Trump appears to want from the arts, so often a source of dissidence. Faced with the prospect of engaging with a cultural sphere that resists his control and his vision, the president would rather, it seems, knock down as much as he can.

The post A Theory of Cultural Life That Is Under Attack appeared first on The Atlantic.