A poet’s collected works don’t need to be read through in order as if they were a novel, just because they’re bound in one volume like a novel. And yet — there’s something novelistic in the experience when you do, reading from youth to death. It gives you a sense of the scale and pace of the writer’s life, an alternate form of biography.

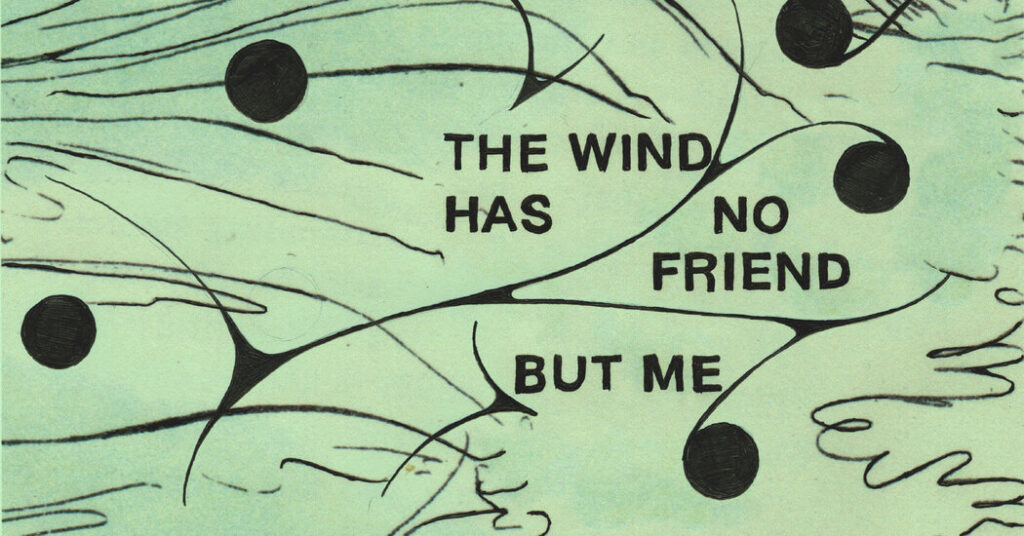

Scale and pace are salient in the work of Larry Levis, who was born to ranchers in Fresno, Calif., in 1946 and died in 1996 at the age of 49, having published five collections of poems in his lifetime. Two more (along with a selected) appeared posthumously. All of these books are now gathered in SWIRL & VORTEX (Graywolf, 557 pp., $35), edited by David St. John, who has kept the first five books intact but reordered the posthumous work, which was originally published in two volumes as “Elegy” (edited by his former teacher and friend of many years Philip Levine, with St. John’s help) and “The Darkening Trapeze” (also edited by St. John). “Swirl & Vortex” also includes several previously undiscovered poems. All together they form a towering body of work by one of the great American poets of the 20th century.

Early books by major writers sometimes feel a little stingy next to the books they become known by, as though they were holding back, when of course the more likely explanation is that they hadn’t yet found the conditions or the method to do their best work. Levis’s early poems are mostly short, wry, imagistic — full of darkness and shadow (“Once I saw my/shadow in water, and/glanced back, but I was gone”) and a melancholy Hemingway rain (“I am a used-car dealer … I am an old Cuban in the rain”). There’s a coolness that reminds me of Denis Johnson (“I steal a car and drive softly away”) or the mildly ironic sensibility of Charles Simic, an eye that sees the world a bit smaller than real size (“Ruled by the longings of toys/left under houses for years. Left as offerings. Dust”).

But already in the early work there were signs of the later, more Levis-y Levis — notably in the sequences of short, thematically connected poems that accrued as numbered sections across multiple pages, such as “Magician Poems” from his first book, “Wrecking Crew” (1972). Each section has its own little title: “The Magician’s Exit Wound,” “The Magician’s Ride to the Hospital.” This is one of Levis’s signatures, this grouping and subtitling and concatenation, as though a linked sequence or even an arrangement decided after the fact always constitutes a meta-poem, deserving of its own name. Names confer soul.

A theme bridging parts is a productive apparatus that allows the poem to build beyond image and miniature scene, implying a world. We see it again in the wonderful sequence poem “Linnets 1–12,” gathered in a section titled “The Rain’s Witness” in Levis’s second book, “The Afterlife” (1977). Here the theme takes on the grandeur of a personal myth. “One morning with a 12 gauge my brother shot what he said was a linnet,” the poem begins. “Anyone could have done the same and shrugged it off, but my brother joked about it for days … He drove on the roads with a little hole in the air behind him.”

In the second section, Levis writes, “I find that I too am condemned, and must stitch together, out of glue, loose feathers, droppings, weeds and garbage I find along the street, the original linnet.” The poem changes form (from prose to lines and stanzas), changes subject like a dream. The poem is capacious and we trust we are still in the same dream. “It is peace time./You have no brother./You never had a brother.”

“The Rain’s Witness” is a variation on a line from one of the sections (“You witness the rain for weeks”), elevated to a name of its own. These marginal, mysterious decisions of ordering and naming are so personal, almost like pet names. They add so much style, a word that was important to Levis, who must have known its part in greatness. Style is defensible idiosyncrasy.

Poets often attach to certain words. Besides “style,” I associate Levis with “stillness,” “goodbye” and of course “rain,” “horses,” “trees,” “stars” and “fire,” words for things so elemental they lose their wordness — we can’t read them without seeing what they name. The earmarked words may be minor for everyone else. Take a word like “even,” as in “You do not even/Have a car anymore.” A small, connective word, but one used to express astonishment. Loss is total.

Levis had ways of giving outsize weight to single words. One was to put the last word of a sentence first on a line — a kind of delayed closure, as in these lines from “Sensationalism,” based on a Josef Koudelka photograph: “It could be wrong to make up anything. Perhaps the man is perfectly/Happy.” It’s an unstable place for resolution, offering little finality and thus little certainty, like the unnatural stillness of high divers just before the dive.

By midcareer, beginning with his third book and on until the devastating poem that St. John believes to be the last he ever wrote, Levis had found the form that made the most of his voice: long, digressive poems that blend the narrative and confessional like a bar stool raconteur, poems that seem to announce their slow pacing and the scale of their intentions from the first line, as in “Those Graves in Rome”: “There are places where the eye can starve,/But not here. Here, for example …” Or “Some Grass Along a Ditch Bank” (both are from “Winter Stars,” from 1985, my favorite of his books): “I don’t know what happens to grass./But it doesn’t die, exactly.”

These midlife books (though Levis tragically didn’t make it past midlife) are a staggering achievement of style entwined with worldview, as humane and attentive to people and other creatures of nature as John Berger, as complex in their philosophy as Hegel by way of Stevens.

His great subjects are nothing and the soul, and in his poetry things are often also their opposite, as a soul is also nothing. “Elegy With an Angel at Its Gate” directly references “The Snow Man” (“a mirror/Reflecting everything & the nothing/In everything”) but dialectical negation is everywhere, especially in the Rilkean elegies: “The motion of their wake is a stillness.” “Glossolalia, he once said, which was all speech, & none.” “How she might have done things differently. But didn’t./How it is too late to change things now. How it isn’t.” “If the soul had a written history,” he writes in “Elegy With a Chimneysweep Falling Inside It,” “nothing would have happened.” “The horse would go on grazing,” as the world goes on in Auden’s poem while Icarus falls.

These are poems that find infinite detail in a void while remembering it’s also really void, like the sky that reveals all its stars every night and removes them again every morning. The starry sky is there and it isn’t. “Oblivion,” Levis wrote, with a heartbreaking wink, “would be nothing without us.”

The post He Died at 49. His Collected Poems Rank With the Best of the 20th Century. appeared first on New York Times.