Inside a lofty gallery at the Fondazione Prada in Milan, a tower standing several stories tall started to dance. “This makes me want to cry,” said its creator, the artist Mona Hatoum — but she was beaming as she watched her complex kinetic sculpture come to life while she readied her exhibition “Over, Under and in Between.”

Hatoum’s soaring tower zigzagged and lurched, buckled and straightened again, its hinged aluminum beams manipulated by overhead cables like a motorized marionette. The gallery itself seemed to shift and tilt.

The swaying monolith was “like the skeleton of a collapsing building or a scaffolding under construction,” Hatoum, 73, said, “falling down like a body and rising again.” Titled “All of a Quiver,” it is a monument to humanity’s cycle of creation and devastation, conjuring bombed-out homes like those in Gaza, but also skyscrapers going up in Manhattan, Milan and elsewhere.

Now perhaps more than ever, her art seems to speak to a sense of risk and upheaval in world affairs — but she’s been sounding the alarm since the outset of her four-decade career.

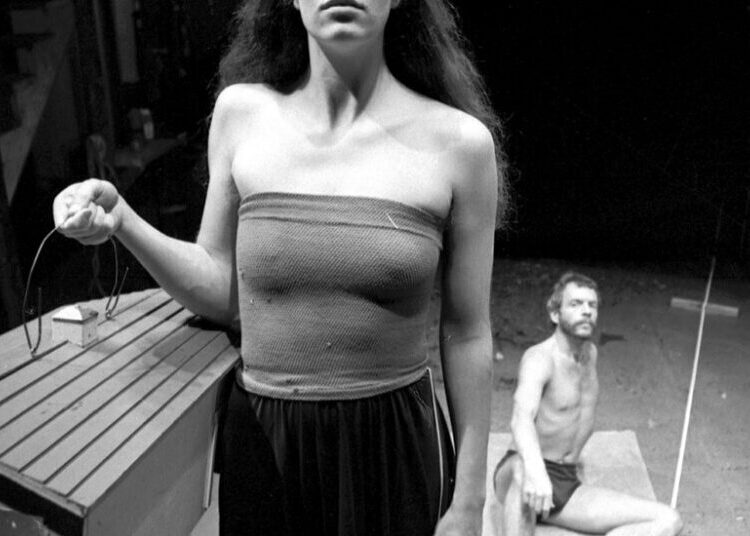

Hatoum was born and raised in Beirut to Palestinian parents living in exile. While she was visiting Britain in her early 20s, the Lebanese civil war broke out, and she never returned home. Instead, she studied art in London and built an international career from there.

While some critics have framed her art within her biography of flight and double exile as a Palestinian, Hatoum said her work is expansive, exploring tensions that everyone experiences in life.

“I create environments that suggest danger and threat, rather than pointing at a specific conflict,” she said, “so they remain open for viewers to bring their own narrative.” Those potential interpretations are always plural: of the vulnerable and violent, the captive and captor, the builder and destroyer, turmoil and the longing for refuge.

As Hatoum checked on progress at the Fondazione Prada, installers unboxed marbles for her immense map of the world, “Map (Red),” filling in the last of the Pacific islands on a gallery’s concrete floor.

The map, composed of more than 30,000 red marbles, embodies the contested nature of the world’s borders, with many of the glass balls spilling beyond the continents’ margins over time. Visitors must stay close to the wall to avoid slipping.

In the next hall, Hatoum paced under the show’s third large-scale installation, which also entwined beauty with danger: a spider web, strung with handblown glass orbs, stretching overhead across the entire vast space — a gossamer trap that makes viewers feel like insects.

“I like to push and pull visitors in two different directions,” Hatoum said, gazing upward.

Miuccia Prada said in an email that it was a “sense of suffering and delicacy” that drew her to admire and collect Hatoum’s art, and, as president and director of the Fondazione Prada, to commission the exhibition.

“For me, her work possesses a universal significance that transcends contemporary political and social issues,” she said. “It confronts us with the cruelty of existence, and transforms objects that should evoke intimacy and familiarity into something else entirely.”

Hatoum has been the subject of many other exhibitions at major museums, including retrospectives at the Pompidou Center and Tate Modern. At the Barbican Art Gallery in London, a double show that closed in January paired her work with the sculptures of Alberto Giacometti.

The juxtaposition of Giacometti’s postwar works, steeped in existential dread, with Hatoum’s creations highlighted the enduring nature of her concerns, explained Shanay Jhaveri, the head of visual arts at the Barbican. “Both artists explore the psychological and emotional impact of violence on humans, and on humanity as a whole,” he said.

At the Barbican, Giacometti’s sculpture, “The Nose,” was encased inside Hatoum’s “Cube,” a cage of steel bars. Nearby, her scorched chairs reduced to ghostly frames of chicken wire — “Remains of the Day,” which won the Hiroshima Art Prize — struck a nerve in a gallery built on a World War II bomb site.

“We are living in the midst of conflicts and strife now,” Jhaveri said, adding that the show in London “became a space for catharsis, as well as reflection.”

One of Hatoum’s major themes, surveillance, first gripped her while she was studying art at the Slade School of Fine Art in London. She said that the city was teeming with security cameras and reminded her of George Orwell’s “1984.”

At the Slade, she created videos and performances that incorporated live footage of the audience — scandalously interspliced with naked body parts — to remind viewers that they were under constant observation. A few years later, she even filmed an endoscopy inside her own body.

“I became very interested in the architecture of control and the architecture of institutional violence,” Hatoum said. “You’re watched by cameras everywhere, with structures designed to spy on you, control you, and confine you to set boundaries so you don’t have any freedom.”

Starting in 1989, while teaching art in Cardiff, Wales, she learned to weld steel and cast bronze, and turned her practice toward materials like barbed wire, rubber, glass and even human hair.

After seeing an Arte Povera show featuring a Pier Paolo Calzolari piece covered in ice by an attached refrigeration unit, she produced “The Light at the End” in 1989: a structure with scalding hot bars that resemble a prison door. The work provoked instinctive bodily reactions and gave form to that “architecture of control,” setting the path for the sculptures and installations that since have defined her art.

Those include “Light Sentence,” from 1992, featuring stacks of wire lockers that recall jail cells or the project buildings of the Paris suburbs, which locals call “cages à lapins” — rabbit cages. A bare lightbulb casts moving shadows through the wire grids, and viewers see their own silhouettes behind bars, producing a visceral sense of confinement and surveillance.

“There’s a certain liberation in making these structures of captivity,” Hatoum said, “in showing people the captivity they’re in. I’m trying to make people realize that there’s danger around us, that there’s a conspiracy to limit our freedom and imagination.”

“I became an artist because I wanted to break free of restrictions ever since I was a kid,” Hatoums added. Growing up as a girl in an Arab society, she “felt the weight of rules and regulations limiting my freedom,” she said, “and I felt that artists had the freedom and the poetic license to defy the rules and be limitless.”

Hatoum has a penchant for refashioning domestic objects into something sinister: an egg-slicer big enough to julienne a full-grown person; a supersize cheese grater turned into a sharply serrated screen. These were echoes of her “frustration with women’s role in the household, stuck in the role of the caretaker,” she said, but also reflected anxieties about losing one’s home, as well as Freud’s idea of the uncanny — the familiar turned frightening.

While her art has sometimes seemed to reference the plight of Palestinians — like a map of the Oslo accords drawn on Nablus olive oil soap and a kaffiyeh scarf woven with a woman’s hair — it is also open to broader readings and encompasses art historical allusions as diverse as Surrealism’s estrangement of the everyday, Duchamp’s transfigured ready-mades, Arte Povera and minimalism.

“What I don’t like is when people come with preconceived ideas that my art is about the Palestinian experience,” Hatoum said. “I come from an embattled background, so ideas of conflict, war, displacement, disorientation, and feelings of isolation enter into the work. The artist’s outlook on life originates in one’s experience — but I’m not directly illustrating my experience.” That experience, she pointed out, also includes 50 years in the West.

Even in contexts far from the artist’s own, the works can hit home, said Chiara Bertola, a curator who has staged exhibitions of Hatoum’s work in South America. In Argentina and Brazil, she said, “Mona’s art resonated immediately because of shared legacies of migration, escape and everyday violence.”

“The instability and insecurity of people, of homes, of borders — these are themes that Mona speaks of from firsthand experience,” Bertola said. “But the whole world is moving deeper into crisis now, and the universality of Mona’s work is only becoming more evident.”

Over, Under and in Between Through Nov. 9 at the Fondazione Prada in Milan; www.fondazioneprada.org.

The post In Her Quivering Art, a Warning for a Wobbling World appeared first on New York Times.