In late May 2020, a man took his dog for a walk along the shore of North Carolina’s Outer Banks and discovered a beach full of confounding detritus. There were tangles of wooden beams, bits of white picket fence, a box spring foundering in the sand — and no indication where any of it had come from.

The mess, it turned out, marked not an arrival but a disappearance. A house — 23238 Sea Oats Drive, in Rodanthe — had washed into the ocean around 1:30 a.m. It left behind nail-studded wood and the shambles of a septic system, but no visual record of the moment when, as The Coastland Times put it, the structure “lost its battle with south swells” and collapsed into the sea.

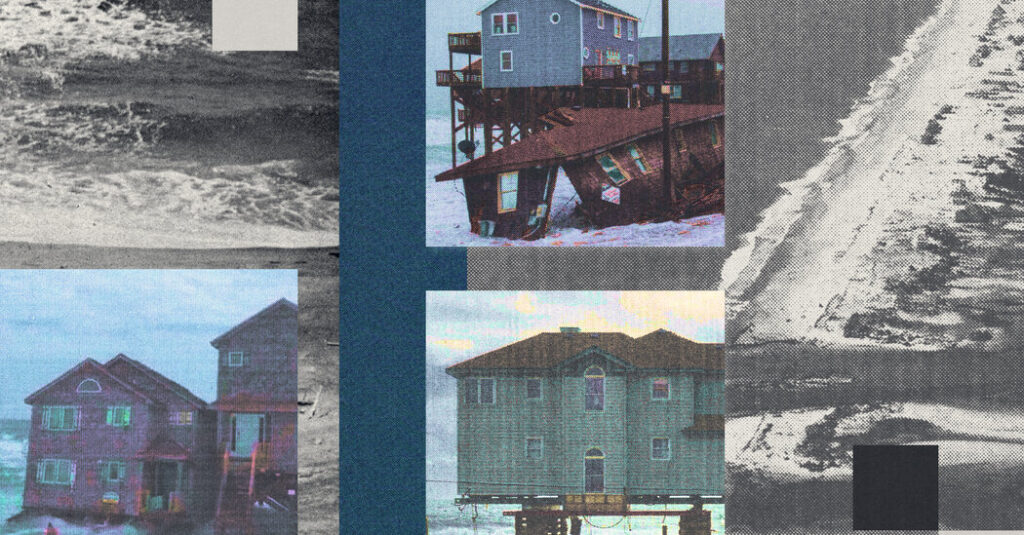

A little less than two years later, another house in Rodanthe collapsed. This time it happened on what the National Park Service, which oversees some 70 miles of seashore around Cape Hatteras, called “a calm winter day,” and there were photos that captured the surreal process — a house where no house should be, its upper half eerily intact while its lower half pancakes into the surf.

Three months after that came a May nor’easter whose accompanying waves sent two more Rodanthe houses into the sea on the same day. This time there was video: You could watch the gangly pilings beneath a two-story building list and lurch and then fall, toppling the house forward like those Imperial Walkers in “Star Wars” and leaving it bobbing in the breakers amid the ruins of its own porches.

Over the last few years, videos of houses collapsing into the ocean off the Outer Banks have become steadily more common. One house went down in 2023, then six in 2024. This year, there have been 16. Many are caught on camera, and the videos regularly go viral. (A September headline in The Washington Post: “Watch the Sea Claim Yet Another House on N.C.’s Outer Banks.”) Who wouldn’t be grimly fascinated by viewing the incredible power of nature, by the incongruous sight of candy-colored beach houses holding together atop buffeting waves, by the primal attraction of watching large things fall down?

The houses are just an unusually visible example of a gamble we are making nationwide.

Judging by the comments on these videos, though, there’s also something else pulling people in: anger and confusion. What kind of idiot, the commenters always want to know, built their house this close to the ocean in the first place? Why were these houses left to collapse into gross piles of ocean pollution, rather than dismantled or moved or recycled in advance? What sort of world would allow this very obviously bad thing to happen, and to keep happening, again and again?

The Outer Banks, a nearly 200-mile long stretch of islands home to a thriving tourism industry, have never been fixed in place. They are sandbars — masses of unconsolidated sand, unattached to the seabed — that happen to sit above the level of the ocean. It is their nature to ebb and flow with wind and tide, providing the mainland with a protective barrier by taking the brunt of storms themselves.

Most of the houses that collapsed were not built in conditions anything like the ones seen in videos of their demise. Even those that are only a few decades old once stood a respectful distance from the water, hidden behind wide stretches of dunes. What looked like solid ground, however, hasn’t stayed that way. As climate change worsens hurricanes and raises seas, the rate of coastal erosion on the Outer Banks has increased rapidly. (And efforts to protect key infrastructure, like the highway connecting the islands, have worsened erosion elsewhere.) The area around Rodanthe is losing some 13 to 15 feet of beach each year — meaning that in 1977, when that house on Sea Oats Drive was built, the waterline that would eventually swallow it was hundreds of feet away.

Many towns try to solve this problem by dredging and pumping sand from elsewhere onto their disappearing beaches. Buxton, a town 25 miles south of Rodanthe, has undergone three major “renourishments” since the mid-1970s. Last year, local leaders decided to move up the next one, originally scheduled for 2027, because erosion was happening faster than expected. Before it could be completed, though, a series of hurricanes spinning far offshore brought strong waves that pounded the beach. Sixteen houses went down in less than a month.

Some houses have been moved away from the water successfully, but there’s only so far they can go before running out of land. Others, tagged as unsafe, sit vacant while their owners wonder what to do. It costs hundreds of thousands of dollars to move a house, and the National Flood Insurance Program, the insurer of last resort for high-risk properties built on coasts and in floodplains, doesn’t cover proactive measures like relocation — it kicks in after there has been a total loss. (Even then, it doesn’t help with cleanup costs, which fall to owners, the Park Service and volunteers.) For decades, experts have warned that the N.F.I.P. is overburdened, and becoming only more so as flooding becomes more frequent and more extreme; they also warn that the program creates perverse incentives by subsidizing insurance in high-risk areas. But efforts to reform it have foundered, in part because doing so might require essentially writing off enormous amounts of “value” stored in properties at risk of flooding. We are too heavily, and too literally, invested in the status quo.

A strange quirk of the Zillow era is that you can easily look up the address of each collapsed house to see its construction and sales history. Some of the fallen have been owned for decades. Others changed hands recently, for tidy sums. One, on Ocean Drive in Buxton, is recorded as having sold for $580,000 in September 2024; on Oct. 28 of this year, it became one of five houses to disappear into the waves in a single day. Sometimes a house has sold at a discount compared with its less precarious-looking neighbors, which makes it easy to imagine the thought process — the calculated gamble of how many years of fun or profit might be left in it, and whether they outweigh the potential losses.

Still, the water rises and more houses tip their contents — fiberglass insulation, toxic chemicals, a novelty pillow — into the sea. If the gamble was a bad one, its losses will be borne not just by the gambler but also by everyone else who will help cover the costs and clean up the mess.

In this sense, the house collapses are not as baffling as internet commenters seem to think. They are just an unusually visible example of a gamble we are making nationwide. We are a country that stores its savings in homes — leaving us, and the entire economy, vulnerable not just to floods and fires but also to the erosion of value that happens when potential buyers can no longer afford spiking insurance premiums, or when water becomes harder to source, or when similar problems diminish the tax base and force cuts to services.

It’s not just houses, either. There is an economic term, “stranded assets,” for holdings that have been considered assets but suddenly become losses, even liabilities, as circumstances change. Climate change is expected to create a lot of stranded assets: snowless ski resorts, unproductive farmland, expensive infrastructure built for conditions that no longer exist, oil deposits or coal-fired power plants that are deemed unwise to exploit. Economists argue that one of the best ways to make this transition less painful is to demand more transparency — to reckon more honestly with how much risk some of our current systems face. In many cases, the ground they are built on is already less solid than we think.

Brooke Jarvis is a contributing writer for the magazine.

Source photographs for illustration above: Daniel Pullen/The Virginian-Pilot/Tribune News Service, via Getty Images; Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post, via Getty Images; Westend61/Getty Images; Screenshot from Reddit.

The post Houses Collapsing Into the Sea? It’s Not as Baffling as It Looks. appeared first on New York Times.