He was a surgical oncologist at a hospital in a Southern city, a 78-year-old whose colleagues had begun noticing troubling behavior in the operating room.

During procedures, he seemed “hesitant, not sure of how to go on to the next step without being prompted” by assistants, said Dr. Mark Katlic, director of the Aging Surgeon Program at Sinai Hospital in Baltimore.

The chief of surgery, concerned about the doctor’s cognition, “would not sign off on his credentials to practice surgery unless he went through an evaluation,” Dr. Katlic said.

Since 2015, when Sinai inaugurated a screening program for surgeons over 75, about 30 from around the country have undergone its comprehensive two-day physical and cognitive assessment. This surgeon “did not come of his own accord,” Dr. Katlic recalled.

But he came. The tests revealed mild cognitive impairment, often but not necessarily a precursor to dementia. The neuropsychologist’s report advised that the surgeon’s difficulties were “likely to impact his ability to practice medicine as he is doing presently, e.g. conducting complex surgical procedures.”

That didn’t mean the surgeon had to retire; a variety of accommodations would allow him to continue in other roles. “He retained a lifetime of knowledge that had not been impacted by cognitive changes,” Dr. Katlic said. The hospital “took him out of the O.R., but he continued to see patients in the clinic.”

Such incidents are likely to become more common, because America’s physician work force is aging fast. In 2005, more than 11 percent of doctors who were seeing patients were 65 or older, the American Medical Association said. Last year, the proportion reached 22.4 percent, nearly 203,000 older practitioners.

Given physician shortages, especially in rural areas and in key specialties like primary care, nobody wants to drive out veteran doctors with skills and experience.

Yet researchers have documented “a gradual decline in physicians’ cognitive abilities starting in their mid-60s,” said Dr. Thomas Gallagher, an internist and bioethicist at the University of Washington who has studied late-career trajectories.

At older ages, reaction times slow; knowledge can become outdated. Cognitive scores vary greatly, however. “Some practitioners continue to do as well as they did in their 40s and 50s, and others really start to struggle,” Dr. Gallagher said.

A few health organizations have responded by establishing late-career practitioner programs mandating that older doctors be screened for cognitive and physical deficits.

UVA Health at the University of Virginia began its program in 2011 and has screened about 200 older practitioners. Only in four cases did the results significantly change a doctor’s practice or privileges.

Stanford Health Care launched its late-career program the following year. Penn Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania also put in place an testing program.

Nobody has tracked how many exist; Dr. Gallagher guesstimated as many as 200. But given that the United States has more than 6,000 hospitals, those with late-career programs constitute “a vast minority,” he said.

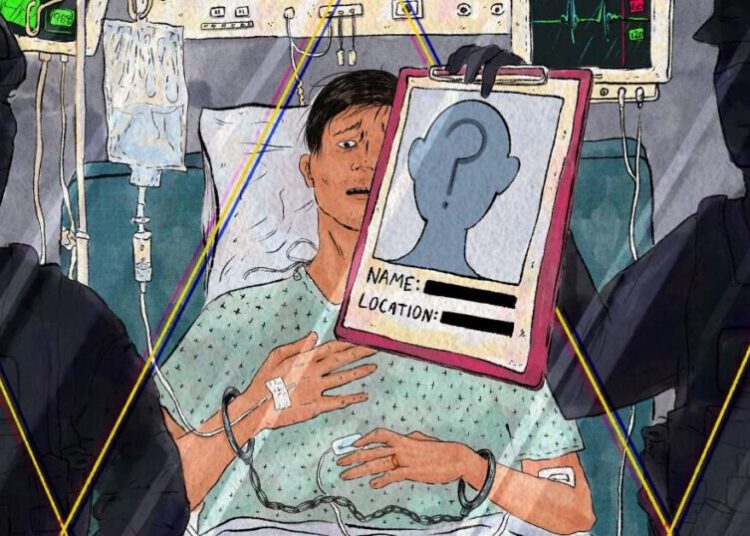

The number may actually have shrunk. A federal lawsuit, along with the profession’s lingering reluctance, appears to have put the effort to regularly assess older doctors’ abilities in limbo.

Late-career programs typically require those over 70 to be evaluated before their privileges and credentials are renewed, with confirmatory testing for those whose initial results indicate problems. Thereafter, older doctors undergo regular rescreening, usually every year or two.

It’s fair to say such efforts proved unpopular among their intended targets. Doctors frequently insist that “‘I’ll know when it’s time to stand down,’” said Dr. Rocco Orlando, senior strategic adviser to Hartford HealthCare, which operates eight Connecticut hospitals and began its late-career practitioner program in 2018. “It turns out not to be true.”

When Hartford HealthCare published data from the first two years of its late-career program, it reported that of the 160 practitioners over 70 who were screened, 14.4 percent showed some degree of cognitive impairment.

That mirrored results from Yale New Haven Hospital, which instituted mandatory cognitive screening for medical staff members over 70. Among the first 141 Yale clinicians who underwent testing, 12.7 percent “demonstrated cognitive deficits that were likely to impair their ability to practice medicine independently,” a study reported.

Proponents of late-career screening argued that such programs could prevent harm to patients while steering impaired doctors to less demanding assignments or, in some cases, toward retirement.

“I thought as we got the word out nationally, this would be something we could encourage across the country,” Dr. Orlando said, noting that Hartford’s program cost only $50,000 to $60,000 a year.

Instead, he has seen “zero progress” in recent years. “Probably we’ve gone backward,” he said.

A key reason: In 2020, the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission sued Yale New Haven over its testing efforts, charging age and disability discrimination. The legal action continues (the E.E.O.C. declined to comment on its status), as does the hospital’s late-career program.

But the suit led several other organizations to pause or shut down their programs, including those at Hartford HealthCare and at Driscoll Children’s Hospital in Corpus Christi, Texas, while few new ones have emerged.

“It made lots of organizations uncomfortable about sticking their necks out,” Dr. Gallagher said.

Instituting later-career programs has always been an uphill effort. “Doctors don’t like to be regulated,” Dr. Katlic acknowledged. Late-career programs have “in some cases been very controversial, and they’ve been blocked by influential physicians,” he said.

As health systems wait to see what happens in federal court, most national medical organizations have recommended only voluntary screening and peer reporting.

“Neither works very well at all,” Dr. Gallagher said. “Physicians are hesitant to share their concerns about their colleagues,” which can involve “challenging power dynamics.”

As for voluntary evaluation, since cognitive decline can affect doctors’ (or anyone’s) self-awareness, “they’re the last to know that they’re not themselves,” he added.

In a recent commentary in The New England Journal of Medicine, Dr. Gallagher and his co-authors recommended procedural policies to promote fairness in late-career screening, based on an analysis of such programs and interviews with their leaders.

“How can we design these programs in a way that’s fair and that therefore physicians are more apt to participate in?” he said. The authors emphasized the need for confidentiality and for safeguards like an appeals process.

“There are all sorts of accommodations” for doctors whose assessments indicate the need for different roles, Dr. Gallagher noted. They could adopt less onerous schedules or handle routine procedures while leaving complex six-hour surgeries to their colleagues. They might transition to teaching, mentoring and consulting.

Yet a substantial number of older doctors head for the exits and retire rather than face a mandated evaluation, he said.

The future, therefore, might involve programs that regularly screen every practitioner. That would be inefficient (few doctors in their 40s will flunk a cognitive test) and, with current tests, time-consuming and consequently expensive. But it would avoid charges of age discrimination.

Faster reliable cognitive tests, reportedly in the research pipeline, may be one way to proceed. In the meantime, Dr. Orlando said, changing the culture of health care organizations requires encouraging peer reporting and commending “the people who have the courage to speak up.”

“If you see something, say something,” he continued, referring to health care professionals who witness doctors (of any age) faltering. “We are overly protective of our own. We need to step back and say, ‘No, we’re about protecting our patients.’”

The New Old Age is produced through a partnership with KFF Health News.

The post When the Doctor Needs a Checkup appeared first on New York Times.