To peer into the future of one of Antarctica’s largest and fastest-shrinking glaciers, scientists on Wednesday began piercing a deep hole through its icy core.

A team of British and South Korean researchers is preparing to use the hole to study the warm ocean currents that are melting the Thwaites Glacier from below. Scientists fear that as Thwaites’s floating ice erodes and weakens, the rest of the glacier could start sliding quickly from the land to the ocean, adding to global sea-level rise.

But Thwaites’s floating end is too large for oceangoing robots to explore the deepest reaches of the waters underneath it. So the best way for researchers to collect data in those waters is by using hot water to bore a narrow hole through the half-mile-thick ice and installing instruments at the bottom.

“We’re just kind of curious to see more of what’s beneath our feet,” said Keith Makinson, an oceanographer and drilling engineer with the British Antarctic Survey.

The hot water first hit the ice on Wednesday evening, after a dinner of stir-fried spaghetti with peanuts and tuna. (After camping for more than a week on Thwaites to set up the drilling equipment, “the food choice is diminishing,” said Peter Davis, another oceanographer on the team.)

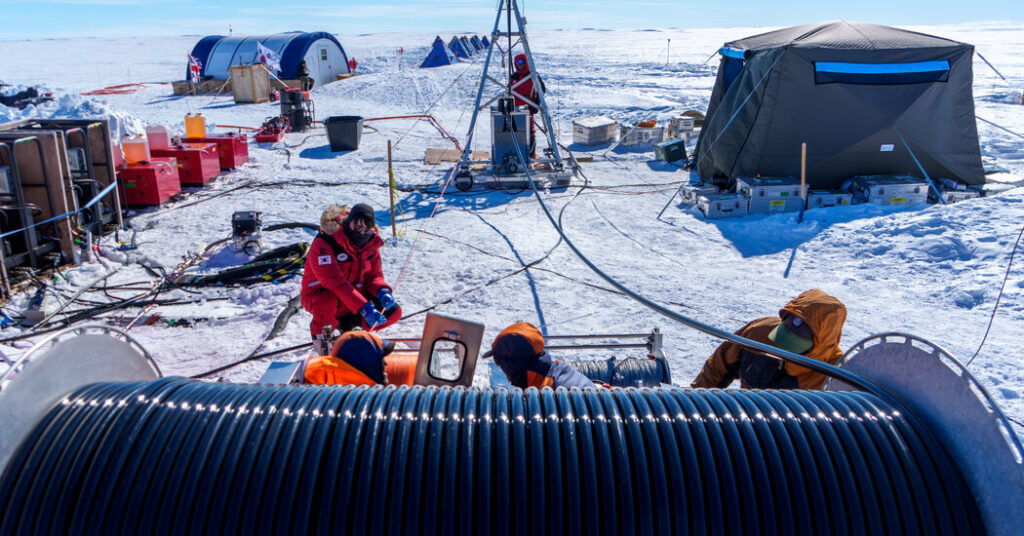

Several members of the 10-person team worked through the night to operate the drilling system, which includes a battery of hoses, winches, pumps, heaters, water tanks and gasoline-powered generators, all of it set up in a vast snowy expanse on Thwaites’s main trunk.

The system heats water to 80 degrees Celsius, or 176 degrees Fahrenheit, and shoots it through a drilling hose with a spray nozzle at the end. The hose can punch through a meter, or more than three feet, of ice per minute near the surface, though the rate slows deeper inside the glacier because the hot water cools on its way down through the hose.

The researchers first bored two holes not far from each other, each one about 375 feet deep. They then connected the holes at the bottom with a bulbous cavity to hold a supply of water for the drilling system. As the hose continued boring down one of the holes, the resulting meltwater would gather in the cavity. From there, it would be pumped up to the surface through the second hole, heated and reused for the drilling hose.

After carving out the cavity on Thursday, the researchers weren’t sure the water recycling system was properly connected inside it. So they lowered a camera to take a look.

Once they had pulled the camera back up, the team members huddled around a laptop to examine the footage from inside the borehole, an experience that Won Sang Lee, the expedition’s chief scientist, compared to watching an endoscopy.

At first, the foot-wide hole looked just like a hole, with white walls that had been left glistening and pockmarked by the rapid melting. Then, starting at around 50 feet beneath the surface, huge chunks of ice seemed to be missing from the sides. These were gaping crevasses, and they seemed to twist and extend deep into the glacier, like yetis’ caves.

Later, these crevasses might prove dangerous for the scientists’ instruments, which could become hooked or trapped while being lowered into the hole. But the fact that the ice was crevassed came as no great shock: It’s because this part of Thwaites is moving so rapidly, stretching and splitting apart in the process, that the research team wants to know what’s going on in the water underneath.

“I’d be surprised if we drilled down and there wasn’t any crevassing,” Dr. Makinson said.

By Thursday evening, the scientists had confirmed that the water recycling system was functioning, and they started the daylong process of deepening the main borehole, down toward a watery realm about which so much is still unknown.

Raymond Zhong reports on climate and environmental issues for The Times.

The post Drilling Is Underway to Examine Antarctica’s Melting Ice From Below appeared first on New York Times.