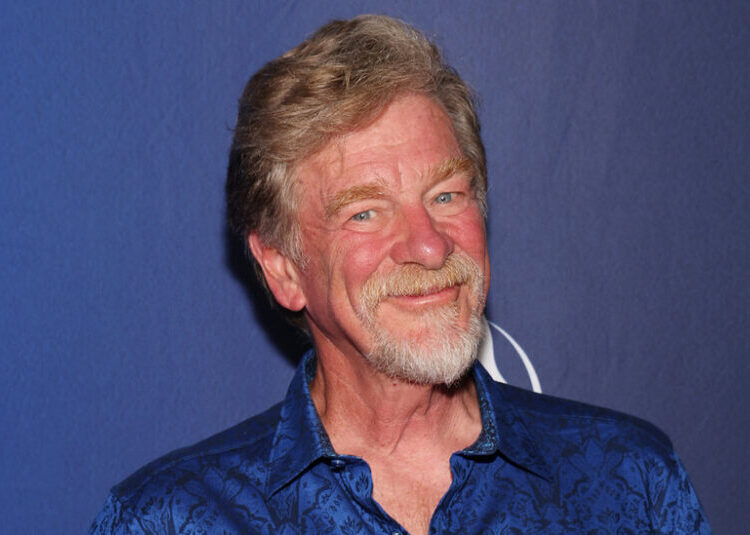

President Trump’s statement nominating Kevin M. Warsh as the next chair of the Federal Reserve was replete with compliments for the 55-year-old former Fed governor with deep Wall Street ties. Describing him as “central casting,” he said Mr. Warsh would “go down as one of the GREAT Fed Chairmen, maybe the best.”

But the president did not shy away from making clear how high his expectations are for what is one of his most consequential appointments of his second term in the White House. “He will never let you down,” Mr. Trump wrote of Mr. Warsh on Friday.

Living up to those expectations will not be easy.

Mr. Trump wants substantially lower borrowing costs and has already gone to great lengths to try to pressure the Fed into delivering them. The broadsides became so extreme that Jerome H. Powell, the Fed chair, blasted the administration after the Justice Department opened a criminal investigation into whether he lied to Congress about a renovation of the Fed’s headquarters. Mr. Powell, who had long avoided responding to any of Mr. Trump’s attacks, called the investigation a pretext to coerce the Fed into lowering interest rates.

The path to the rock-bottom rates Mr. Trump demands is riddled with roadblocks. The economy, which is growing steadily, simply does not call for the roughly 1 percent level that Mr. Trump desires. Officials at the central bank know this, which is reflected in their nearly unanimous decision this week to hold rates steady in the 3.5 percent to 3.75 percent range.

Mr. Warsh’s reputation also stands in the way of the president getting what he wants. To be seen as a credible chair, Mr. Warsh cannot pursue monetary policy decisions that are inconsistent with the incoming economic data or risk stoking fears about the central bank’s commitment to keeping inflation low and stable.

“He’s going to try to thread the needle of respecting President Trump’s wishes and at the same time respecting institutional processes,” said Dennis Lockhart, who overlapped with Mr. Warsh while at the central bank when he served as president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta between 2007 and 2017. “Believe me, that’s going to be quite the tap dance. It’s going to be Fred Astaire as central bank chair.”

Resistance to Rate Cuts

The resistance to rate cuts could be quite fierce from both inside and outside the central bank if the economy continues to hum along in the coming year as expected. If he is confirmed by the Senate, Mr. Warsh will not preside over a Fed meeting until June, meaning the backdrop could look very different at that stage.

But if economists’ forecasts are even remotely accurate, growth is poised to pick up, the labor market will stabilize and inflation will only gradually ease. There is still likely a path to cut in that environment, but much more gradually than what the president wants.

For that to change, the labor market would likely have to show notable signs of weakness — well beyond what the bulk of policymakers are predicting.

Rate decisions are voted on by the 12-person Federal Open Market Committee, which is made up of the seven board members in Washington, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and a rotating set of four other regional presidents. This year’s F.O.M.C. will include at least three presidents who have been highly skeptical about the need to lower rates further. They include Neel T. Kashkari of the Minneapolis Fed, Lorie K. Logan of the Dallas Fed, and Beth M. Hammack of the Cleveland Fed.

The Fed chair has sway over the scope of the debate around rates and other policy decisions, but only confers one vote, meaning Mr. Warsh will need to convince his colleagues. Fed chairs in recent decades have sought to forge as large a consensus as possible, which has been seen as crucial for the central bank to be able to clearly communicate its policy views and steer the economy effectively.

“You don’t want to feel like you’re being dragged along with somebody else’s policy,” said James Bullard, who overlapped with Mr. Warsh while he served as president of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. “If you don’t feel like it’s the right policy — and everybody takes their role very seriously — they’re just going to say, ‘No, I don’t think that’s the right policy.’”

That, said Mr. Bullard, who is now dean of Purdue’s business school, “would make the chair’s job very difficult.”

Financial markets are likely to also revolt if there are concerns about the policies that Mr. Warsh is pursuing, potentially leading to higher long-term rates.

“To maintain market confidence and credibility, much like any Fed chair, Kevin can provide a solid analytical foundation based on data and economic models for his views,” said Randall S. Kroszner, a University of Chicago economist who served as a governor at the central bank alongside Mr. Warsh.

“That is also how to be most persuasive with his colleagues to influence the decisions of the F.O.M.C.”

A ‘Swiss Army Knife’

Those who know Mr. Warsh say he will be adept at handling this challenging environment, while also following through on his call for “regime change” at the central bank.

As the monthslong, highly publicized audition process for the job stretched on, Mr. Warsh, who almost became Fed chair in Mr. Trump’s first term, positioned himself as someone who knew how the central bank operated after his roughly five-year stint as a governor. He served during the global financial crisis and was “very valuable,” according to Donald Kohn, who was vice chair at that time and worked closely with Mr. Warsh.

“He can read a room,” Mr. Kohn added. “He can figure out what the prevailing mood is and what he needs to do to bring the room with him.”

While at the Fed, Mr. Warsh consistently expressed concerns about budding inflation and wanted the central bank to be more circumspect about its crisis-fighting tools, including its decision to forcefully step into financial markets and buy government bonds in what became known as “quantitative easing.”

He carried that view into his subsequent roles after leaving the Fed, working with the billionaire investor Stanley Druckenmiller and as a senior fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution. Mr. Warsh, who is often branded as an inflation hawk, has shown flexibility in that view when the economic conditions shift. A 2018 opinion piece with Mr. Druckenmiller called on the central bank to “pause its double-barreled blitz of higher interest rates and tighter liquidity.”

More recently, Mr. Warsh has argued that there is scope to lower rates because higher growth does not necessarily lead to elevated inflation if it is accompanied by rising productivity, as he contends is happening now with the emergence of A.I., but also that Mr. Trump’s tariffs are not as inflationary as many fear. Mr. Warsh has also tied lower rates to a broader plan to shrink the Fed’s footprint in financial markets and scale back the size of its $6.5 trillion balance sheet.

Mr. Druckenmiller described Mr. Warsh as a “Swiss Army knife.” He said he had “been through the gauntlet” and had exactly the financial markets experience that is crucial for the job. The Fed already stopped shrinking its balance sheet earlier this year, ending a process that is known as quantitative tightening, or Q.T., after there were tremors in short-term funding markets. Pursuing a much smaller balance sheet, as Mr. Warsh has called for, will need be to carefully managed, which Mr. Druckenmiller said he expected him to handle well.

“He’s been in markets, he’s been in the Fed, and he’s not going to be stupid enough to do Q.T. and cause an economic meltdown,” said Mr. Druckenmiller. “He definitely has the market savvy not to do it at the wrong time, if at all.”

“He knows how to deal with people, and I think he’ll handle it as well as it could be handled,” Mr. Druckenmiller added when asked how Mr. Warsh would deal with the potential political pressure from the president. “There may be no tension, because I can’t rule out the scenario where we have high growth and low inflation. I’m open-minded to anything.”

Others who have known him for decades believe Mr. Warsh will not jeopardize his reputation in order to please the president, something that Mr. Powell has been lauded for while chair.

“Kevin will only push for large interest rate cuts if he thinks they make sense,” said Michael Boskin, who works at the Hoover Institution and served as chair of the Council of Economic Advisers during the presidency of George H.W. Bush. “He’s going to form his own judgments.”

That assurance is important at a time when there are acute concerns about the Fed’s ability to operate free of political meddling after the onslaught of attacks against the institution just in the last year. It will also mean that Mr. Warsh will be under heightened scrutiny when he eventually takes over, with every decision closely parsed for any undue influence.

“Whatever his thoughts on interest rates, I know Kevin understands the importance of Fed independence,” said Elizabeth A. Duke, a former Fed governor who also overlapped with Mr. Warsh at the central bank. “Hopefully, with his confirmation, Kevin can negotiate a cease-fire in the attacks on Fed independence.”

Colby Smith covers the Federal Reserve and the U.S. economy for The Times.

The post President Trump Wants Lower Rates. Warsh Could Have a Hard Time Delivering. appeared first on New York Times.