Five years ago, local police departments faced a tidal wave of criticism over racial profiling and the unnecessary killing of unarmed people. Many citizens looked to the federal government to rein them in.

Now the tables have turned. It’s police officials who are complaining about federal agents, saying they are endangering residents and violating their civil rights.

Police chiefs who have spent half a decade trying to persuade a skeptical public that officers would curb their use of violence are contending with widespread alarm over federal officers ushering an innocent man into the snow in his shorts, arresting a 5-year-old and killing U.S. citizens. While local officials have vowed to hold officers accountable for misconduct, Trump administration officials have been quick to declare that their agents did nothing wrong.

Some chiefs have worried that the fragile trust they have worked toward is coming rapidly undone.

“It’s all just going down the toilet,” said Kelly McCarthy, the police chief in Mendota Heights, a Minneapolis suburb. “We do look good by comparison — but that won’t last because people are really frustrated.”

Trump administration officials have defended their operations and blamed state and local officials in Minnesota for the unrest, saying they have incited insurrection and failed to assist federal agents.

Some local departments have taken steps to distance and differentiate themselves from Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers and Border Patrol agents. The city of St. Paul, Minn., has distributed photos showing what their police, fire and animal services uniforms look like. “St. Paul Police Department does not ask people about their immigration status” and “cannot impede or interfere with federal agents,” one advisory said.

On tJan. 20, top brass from about a dozen Minnesota police departments held a news conference to say that while they had nothing against immigration enforcement, they were receiving “endless complaints” about the behavior of federal officers and that city employees and off-duty officers had been illegally stopped on the basis of their skin color.

“It’s impacting our brand as police officers, our brand of how hard we work to build trust,” said Chief Mark Bruley of Brooklyn Park, another Minneapolis suburb.

The grievances are not limited to the Twin Cities. In Maine, a sheriff complained about “bush-league policing” after one of his correction officers, who he said was authorized to work in the United States, was detained by ICE officers. In Brookfield, Ill., outside Chicago, an ICE officer was charged with misdemeanor battery after a man reported that he had been attacked while trying to film the officer.

The criticism aimed at federal agencies is tinged with the irony that for years, the federal government was the nation’s policing watchdog. But under President Trump, the Justice Department has walked away from efforts to force deeply troubled departments to improve — efforts that some chiefs had called intrusive and heavy handed.

The Justice Department announced plans to drop federal oversight of the Minneapolis and Louisville Police Departments last year, within days of the fifth anniversary of the very episode that triggered so much soul-searching over American policing: the killing of George Floyd, a Black man, by Minneapolis officers.

State and local officials have no comparable tool with which to hold federal agencies to account, but elected prosecutors are investigating reports of abuse and conferring on how they might curb warrantless entries and unlawful detentions.

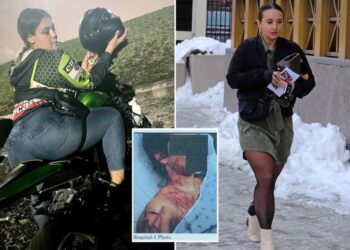

Longtime critics of American policing were quick to say that they remain frustrated with local departments and that people in some predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods still regard the police as an occupying force. DeRay Mckesson, the executive director of Campaign Zero, which seeks to reduce police violence, said he believed the recent violence by federal officers — and the fact that the victims in the two fatal shootings, Renee Good and Alex Pretti, were white — could lead more people to demand more accountability from law enforcement.

“ICE has helped people understand that the system is broken, that it’s not just one or two bad officers,” Mr. Mckesson said.

He pointed to Trump administration accounts of the shootings that were contradicted by bystander videos. “People are for the first time are like, ‘OK, the government’s lying to me,’” Mr. McKesson said. “Before, that would have sounded like a conspiracy theory.”

For one former police chief, Brandon del Pozo, the contrast with ICE is an opportunity for local departments to show that they are committed to improving even when no one is compelling them to do so.

“Never before in our lifetime have they had a better foil than they have in ICE,” Mr. del Pozo wrote in Vital City, a Columbia Law School journal that covers urban issues. “The nation’s attention is rightly focused on flagrant abuses at the federal level that constantly dominate the news and provide a clear moral compass for how police shouldn’t behave,” he added.

ICE has not learned the central lesson that the nation’s police departments learned after Mr. Floyd’s death, said Jerry P. Dyer, the Republican mayor and former police chief of Fresno, Calif. “In order for police to be accepted in communities, they have to have permission to police those communities from the people who live there,” he said.

Instead, Mr. Dyer said, federal agents are not using policing techniques that build trust, like de-escalation and the use of body cameras. “They’re not trusted because of the manner in which they operate,” he said.

Mr. Dyer and other police officials said they had no problem with immigration enforcement, done properly. And many Americans support the Trump administration’s immigration crackdown. Differing views have translated into conflictingrequests for local departments, with some residents asking the police to do more to assist federal agents, while others demand that the police block or even arrest them.

Even when local officers are doing neither, their very presence on the scene can be viewed as siding with or protecting federal agents. And while they are taking the heat from the public for not doing more, or less, they are also experiencing treatment not unlike the kind that have long generated civilian complaints against the police.

Chief Bruley described an incident where, he said, an off-duty officer in her car was illegally stopped by federal agents and asked to provide proof of citizenship. When she tried to take a video of the encounter, her phone was knocked out of her hands, he said.

When he tried to get answers, he encountered another chronic problem that some local departments have been pressured to fix — a lack of transparency. “When you call ICE leadership or you call Border Patrol leadership or you call Homeland Security leadership, they’re unable to tell you what their people were doing that day,” the chief said, adding, “They like to give you a website to go file a complaint.”

For her part, Chief McCarthy said that on a recent day when she was off duty, she had gone, out of uniform, to act as a legal observer outside an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting conducted in Spanish near her home. There, she encountered a Border Patrol agent.

“He told me to get a job, and that I was a paid agitator,” she said. “I would have been embarrassed if he had been one of my officers.”

Shaila Dewan covers criminal justice — policing, courts and prisons — across the country. She has been a journalist for 25 years.

The post ‘It’s All Just Going Down the Toilet’: Police Chiefs Fume at ICE Tactics appeared first on New York Times.