In Iowa, food stamps can be used to purchase ice cream at a convenience store, but not a fruit cup with a fork attached. Next month, consumers in Idaho will be able to use Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits to buy a Twix candy bar, but not a flourless granola bar with chocolate chips.

And in April, government assistance can be used in Virginia to pay for sweetened iced tea and lemonade, but not some brands of sparkling, sweetened fruit juice. The opposite will be true in Texas.

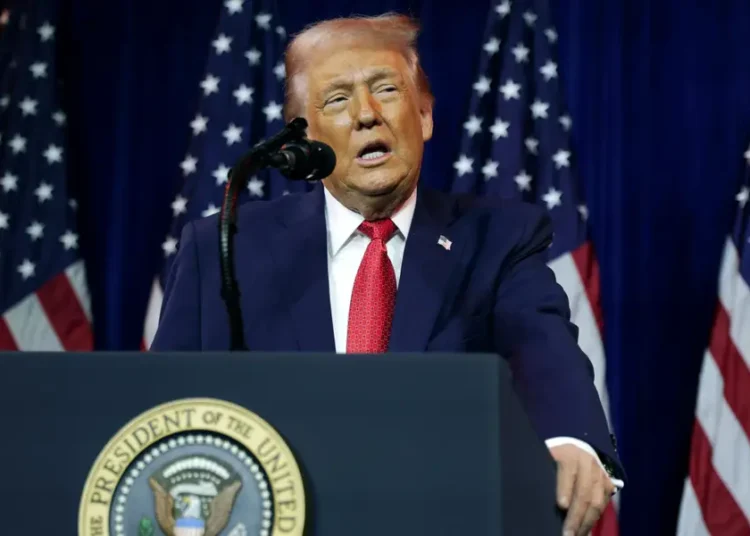

The Agriculture Department, which administers SNAP benefits, is rapidly approving waivers for states to ban the purchase of soda, energy drinks and, in some states, candy or prepared desserts using food stamps. It’s part of the Make America Healthy Again push by the Trump administration, spearheaded by the health secretary, Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

The first restrictions took effect on Jan. 1 in five states: Indiana, Iowa, Nebraska, Utah and West Virginia. At least 13 more states will follow suit in the coming months.

The patchwork of restrictions among states is also creating a bit of a logistical nightmare for grocers — particularly small ones — that have to customize their payment systems in each state. And there’s confusion among consumers left wondering whether the foods and treats they usually purchase with SNAP dollars will remain eligible.

Supporters hail the removal of “junk food” from the program, noting its links to obesity and chronic diseases like diabetes. But others view the changes as an attack on lower-income individuals.

“By placing restrictions on what items disabled and low-income Iowans can buy with SNAP, they are declaring that they don’t trust their constituencies to make decisions around their own health,” said Sarah Jean Ashby, a 33-year-old in Altoona with multiple chronic illnesses that have left her unable to work. She relies solely on the $217 she receives each month from SNAP to buy her groceries. “They’re saying poor children don’t deserve fruit snacks or chocolate on their birthdays.”

The ripple effect from the restrictions will also have financial implications for food and beverage manufacturers, which have experienced a decline in product demand for nearly two years.

The state SNAP restrictions are “another headwind for the industry,” said Spencer Hanus, an analyst at Wolfe Research. He noted that beverage makers had slightly more exposure to SNAP benefits, pointing to a summary from 2016 — the latest figures available — by the U.S.D.A. that showed the second-highest expenditure of recipients was for sweetened beverages, including soda.

Early in the new year, when Iowa’s new restrictions went into effect, Tiffany Carpenter strolled into a Sam’s Club near her home in Cedar Rapids to shop for groceries, nervous about what she could and couldn’t purchase with SNAP funds.

Pop-Tarts? Yes. Scooby-Doo graham crackers? Yes. But Welch’s fruit snacks? No. “These are snacks normal people buy their children,” said Ms. Carpenter, 37, who began receiving SNAP benefits two years ago when she left her job as a Starbucks barista to care full time for her autistic son and two other children. “I fear it’s a slippery slope to them banning a lot in the future.”

For retailers, the new restrictions require them to go into their point-of-sale systems and remove items that are no longer eligible for SNAP spending. Stores must also educate customers and train employees on how to delicately inform shoppers that certain items in their carts may no longer be allowed.

“It’s not the governor who is going to be standing behind the counter explaining the changes. It’s going to be an 18- or 19-year-old employee explaining complex changes to this system,” said Margaret Hardin Mannion, the director of government relations for the National Association of Convenience Stores.

Iowa’s rules are considered the most restrictive, allowing the use of SNAP benefits to purchase only food and beverages not subject to the state’s sales tax, resulting in a byzantine list of prohibited and exempted foods.

Under that definition, benefits can be used to purchase most Nature Valley granola bars because they contain flour, but not the Nature Valley protein bars that don’t. Snickers are not allowed as a candy bar, but are permitted in ice cream form because those are refrigerated and contain milk. Kettle corn can be purchased only if unpopped.

Dion Pitt, the owner of Logan Super Foods, a family-owned grocery store that serves the 1,400 people who live in Logan, Iowa, said it had taken his wife about three days walking the store’s aisles with her laptop to change the codes on hundreds of items that were no longer SNAP eligible in the store’s payment system. Despite the extra hours, he supports the state’s move to restrict some items.

“Pop, candy, that kind of stuff — it should have never been included all along,” Mr. Pitt said. “But the juices and the granola bars, I kind of wish they had left that stuff alone.”

Still, because the definition of “soft drink” or “candy” varies from state to state, the list of prohibited items will, too. While many states prohibit sugary drinks altogether, Texas and Hawaii have specific caps on the amount of sugar or sweeteners. Some states exempt 100 percent fruit juice drinks, but others allow beverages with just 50 percent juice. Hydration drinks, like some forms of Gatorade, are allowed in some states and not in others because of high sugar levels.

“This is causing massive confusion within the retailer community, because there’s limited consistency among states’ waivers,” said Stewart Fried, a principal at Olsson Frank Weeda Terman Matz, a law firm that represents retailers on SNAP and other nutrition policy issues.

Previously, retailers could mark entire categories of products — like alcohol, tobacco and prepared hot foods — as ineligible for SNAP purchases. But now, they must determine if individual items qualify under the new restrictions.

Agencies administering SNAP in Texas and Indiana said they had launched outreach campaigns to inform retailers and SNAP participants about the new restrictions, including sending postcards and emails, conducting conference calls and hosting question-and-answer forums.

But some retailers and anti-hunger groups say states have not done enough to prepare consumers and stores for the changes. Only two — Nebraska and Oklahoma — have circulated lists of specific product codes so far, Mr. Fried said.

Indiana opted to not share product codes given the difficulty of ensuring accuracy, a spokesman for the state’s Family and Social Services Administration said.

Acknowledging “significant challenges” with implementation, the Agriculture Department said in a memo in late December that retailers would have 90 days to comply with the new restrictions. But the agency warned that two violations of the new restrictions could result in consequences, including removal from the SNAP program.

Mike Wilson, the chief operating officer of Cubby’s, a family-owned chain of 41 convenience stores and supermarkets in Iowa, Nebraska and South Dakota, said it had taken about 500 hours to manually compare the affected products and make the changes to the stores’ payment systems. But it’s inevitable that something is going to be missed, he said.

“Nebraska gave us a list with 6,000 items on it, and right away we found a Monster energy drink that wasn’t on it,” he said. Mr. Wilson removed the product from the stores’ payment system, fearing it would be flagged as a failure in an inspection.

The risk of being removed from the program for repeated failures makes Mr. Wilson nervous. In some rural areas, Cubby’s has an expanded store model; in Shelby, Neb., for instance, it is the only grocery store for the community of about 700 people.

“If we make a mistake and don’t flag something that is now ineligible for SNAP funds and they take away our license, it’s not going to hurt Cubby’s. It’s a small part of our sales,” Mr. Wilson said. “It’s going to hurt the people in that community who are poor or have food insecurity. To me, that’s not fair.”

Graphics by Rebecca Lieberman.

Product photos, clockwise from top left: Lori Van Buren/Albany Times Union, via Getty Images; Evemilla/Getty Images; Newscast/Universal Images Group, via Getty Images; RXBAR; Ullstein Bild/Getty Images

Julie Creswell is a business reporter covering the food industry for The Times, writing about all aspects of food, including farming, food inflation, supply-chain disruptions and climate change.

The post Twix is OK but Granola Isn’t as States Deploy New Food Stamp Rules appeared first on New York Times.