As a 23-year-old up-and-coming actress, Aliza Kate Barlow was simply excited to get work when a friend introduced her to an emerging industry: microdramas.

“He was like, ‘You would be perfect for it, you’re white,’” she told TheWrap about the medium’s embrace of broad archetypes. “It’s a thing in the verticals — they love their white, blonde lead girls.”

It’s a glib assessment that speaks to the formulaic nature of these shows. U.S. microdramas, also known as vertical dramas, predominantly star attractive — and white — men and women who follow a predictable romance story. But after starring in four series, Barlow took an indefinite break from the medium, citing the prevalence of graphic content and rapid production schedules.

“I don’t know who would enjoy watching somebody get sexually assaulted, grabbed or abused,” Barlow said.

The $11 billion market for microdramas — short, pulpy shows made up of minute-long episodes designed to be viewed on phones — has attracted Hollywood thanks to their tremendous growth in viewership and revenue. But less has been said about what goes into making them. Microdramas profit by operating at shoestring budgets, employing nonunion talent and churning out as much content as possible with most platforms producing about 40 verticals a month. The grueling schedules and exploitative content, which one actor called “repugnant,” also churns out talent.

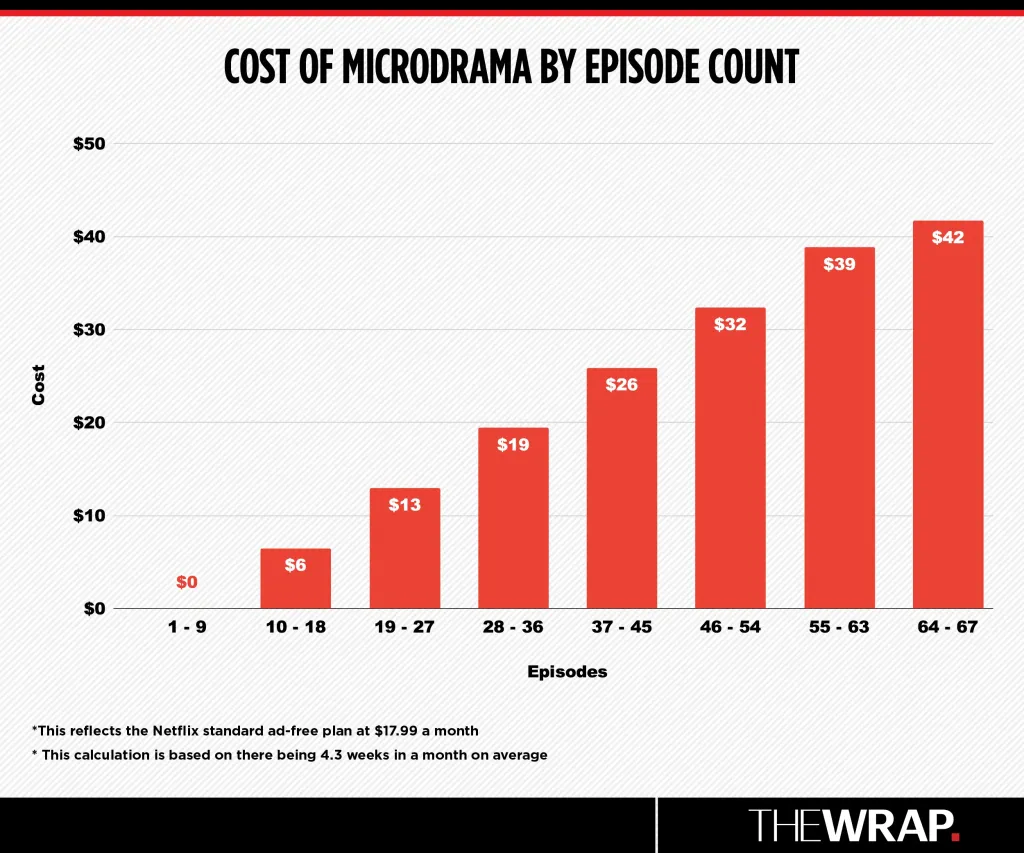

Also problematic is how they make money off of their most loyal fans. Many microdrama companies use the freemium model that’s popular with mobile games, where the first eight to 10 episodes are given away for free, with users ultimately having to pay for the bulk of the episodes — a model that works particularly well for the medium given its penchant for cliffhangers. It’s not uncommon for viewers to pay $40 to finish a single show or pay $20 a week to a microdrama streamer.

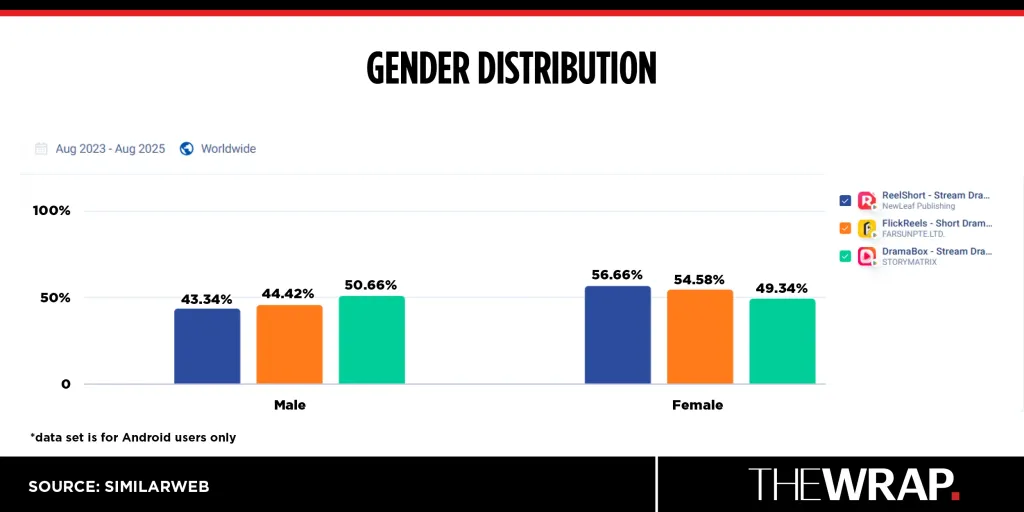

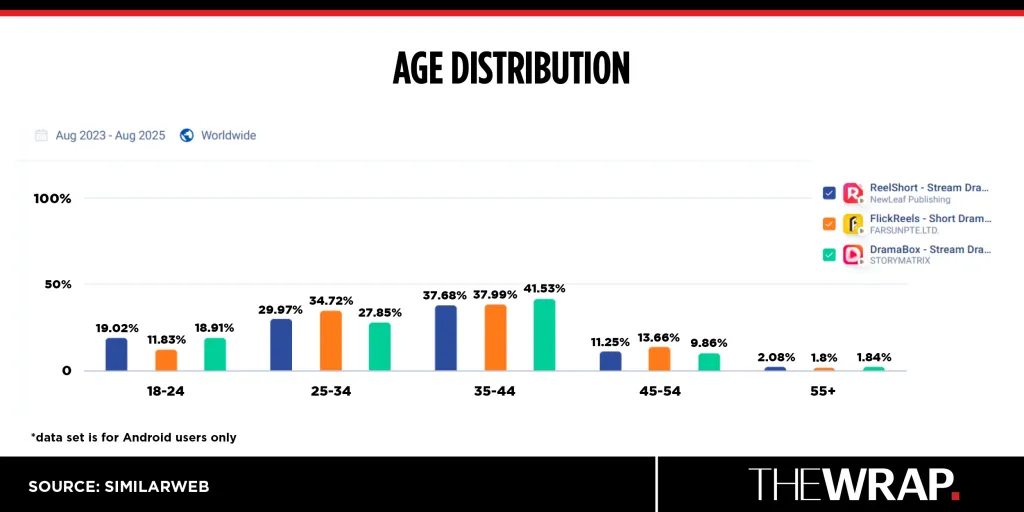

This model, which steadily delivers a trickle of new episodes, is especially successful with romance fans, an audience known to rapidly consume new content. But other genres, like action or comedy, have yet to find a foothold, raising the question of how big the potential microdrama audience really is.

None of this has slowed the microdrama train. As of September 2025, DramaBox’s U.S. user base grew by 84% compared to the previous year, according to data from Similarweb, and ReelShort’s user base grew 45%. Holywater, the Ukrainian vertical streaming company behind MyDrama, raised $22 million in a new funding round and is backed by Fox Entertainment. The app also announced a 40-title deal with Dhar Mann, a creator known for his scripted content with 26.7 million YouTube subscribers. TikTok has also gotten into the microdrama game with the launch of PineDrama.

Given all of the red flags, are these companies walking into a gold mine or a minefield?

Representatives for ReelShort, DramaBox, MyDrama and GoodShort did not respond to TheWrap’s request for comment.

“Exhausting and triggering”

The two actors, writer and director who spoke with TheWrap described the sets of the vertical shows they worked on as positive and supportive, but what irked them all was the explicit, often exploitative nature of these shows.

Barlow’s first and most popular project was “Shh … We’re a Secret,” which garnered nearly 50 million views on DramaBox. Its content also made her the most uncomfortable.

The soapy microdrama follows two step-siblings in a will-they, won’t-they relationship and contains a sexual assault scene that took two hours to film — a far cry from the 30 minutes most microdrama scenes take to film. Though Barlow had an intimacy coordinator and felt safe, it was “triggering” to stay in that environment, especially with actors who did not have time for proper training, she said.

Several of the shoot’s background actors had no prior experience, a common occurrence on microdramas. Barlow noted they “weren’t great at grabbing my arms the way they’re supposed to.”

“It made it a more uncomfortable experience because those people didn’t have the proper monitoring,” she said, noting that due to limited rehearsal time and quick shoots, extras would not have the same oversight they may have on other sets.

One scene in particular pushed Barlow to reconsider the verticals industry. The scene asked her to appear in lingerie and portray a character being physically overpowered by two men. Barlow again noted that there was an intimacy coordinator and the set felt safe, but the content was jarring for a relatively green actor.

“When you put yourself in that world as an actor … and also with whatever I’ve gone through in my own personal life, it can be really hard,” she said.

Compounding that discomfort was the project’s success. The scene that proved most emotionally taxing for Barlow — in which her character is sexually assaulted — performed the best, generating the highest viewership of any vertical she had appeared in. The response from the microdramas audience made Barlow rethink her approach to the format.

“It kind of turned me off of verticals for a second. I made damn sure to read the next scripts,” she said. “If something like that’s in the script, I’m not going to tell myself, ‘Oh yeah, I’ll be fine.’”

More experienced vertical actors can have more control over the content. That’s what JT Garcia, an actor who’s been booking one to two verticals a month since April, experienced. The more he filmed, the more conversations he had about adjusting the material to be less demeaning towards women.

“You’ll have moments in these stories that are, frankly, repugnant,” Garcia told TheWrap. “There are definitely some circumstances where my co-star and I have got together and said, ‘We’re not doing this.’”

The pay rate for microdramas doesn’t do much to offset these moral concerns. Nonunion day players are paid a minimum of $250 per day with leads negotiating rates of $1200. Molly Anderson, who has has appeared in 40 verticals and will be working as a writer in 2026, has also been outspoken about the pay disparity between male and female actors, a discrepancy that is especially damning considering what female performers are required to do.

“I love to give my day players quippy lines about how insane the situation is,” Anderson said, “or let the protagonist acknowledge, ‘I’m having, quite literally the worst day of my entire life. It’s not even noon yet, and I’ve already been kidnapped. I’ve lost my fortune. I had an arranged marriage. I found out I’m pregnant and it’s 1 p.m. I’m exhausted.’”

“That’s how we feel as actors and as people making them,” she added. “You go through all this s–t and they’re like, ‘OK, next up, you’re getting waterboarded in the bathroom,’ and you’re like, ‘OK, Jesus Christ, it’s 8 a.m. I’ve had half a coffee, and off I go to get beat again.’”

A romance bubble?

It’s not a coincidence that most microdramas are romances. The predictable beats of the genre and consumption habits of romance fans align well with the release models for these shows.

In the book world, romance readers are often voracious. The category has also taken off in recent years. Print sales of romance novels in the U.S. have doubled in the last five years, while shows like “Heated Rivalry” and “Bridgerton” have developed strong followings.

But the outsized performance of this specific genre of microdramas could mean that the format overall won’t necessarily scale.

“Everyone has a huge blind spot for romance in Silicon Valley and in Hollywood,” Tiffany Shan Li, a creator and romance fan who often posts about microdramas on TikTok, told TheWrap. “People mistake romance-specific phenomena for broader phenomena. The success of microdramas does not mean people want thriller microdramas or sitcoms as microdramas.”

Minda Smiley, a senior analyst at eMarketer, is more optimistic, pointing to how more Americans have adopted vertical content thanks to apps like TikTok, Instagram Reels and YouTube Shorts. “All it takes is one series or creator to really have success, and then sometimes things take off,” she said.

There’s another reason why these microdramas all tend to follow the same predictable tropes: the algorithm. The key to writing a successful vertical is writing for the algorithm, Anderson said. The romance genre succeeds on these platforms because the same tropes — be it werewolf dramas or step-sibling hookups — get regurgitated. But adhering to what works statistically often conflicts with what the talent and crew wants to do creatively.

“The algorithm sucks. It’s the enemy. It’s also the conduit and the thing you require,” Anderson said. “When it comes to writing, we talk about wanting to tell these more profound stories that have deeper elements and create a more cinematic vertical, but the data and the algorithm disagree.”

Churn and burn

Rapid production schedules are essential to profitability, but they’re also the cause for high turnover in the industry and burnout from some of its stars.

Microdrama shoots typically last from eight to 10 days, filming up to 20 pages a day. For reference, an average sitcom shoots five to six pages a day. Because of the time constraints, new-to-set actors have very few takes. One commenter on Reddit complained of “terrible” pay rates as well as 12- to 13-hour days.

The unique one-minute episodic nature of the content requires quick setups and high stakes drama, according to Danny Farber, who has directed 25 verticals to date. Because the productions are largely nonunion, many of the actors are new to sets.

“Just like soap operas were back in the early 2000s and ’90s, it’s a training ground to get your lines down and hit your marks and maybe do a little acting when the opportunity presents itself,” Garcia shared.

For Farber’s first microdrama, he received a 77-page script and had just eight days to prep.

“It’s exhausting,” he told TheWrap. “But it is a life changing amount of exposure, opportunity, financial income and networking that I would have never been able to experience without access to these verticals.”

A predatory payment structure

A major reason why the microdrama market seems like a potential cash cow comes down to the payment structures these services employ.

Take the series “The Words” on ReelShort, a show about a rocker bad-boy and a nerdy good-girl. The first nine episodes are available to watch for free. But the 10th episode requires users to pay 60 coins, ReelShort’s form of currency. Watching all the episodes so far would cost you just under $42 to view about two hours and 15 minutes of content.

On set, directors make special note of paywalled scenes. “The directors would talk about it and say, ‘OK, this is the paywall part right here,’” Barlow said. “They’re like, ‘Make it good. This is where we’re gonna make the money.’”

The paywall typically comes at the inciting incident of the drama, where the main character will make a big decision — Will she hook up with her stepbrother? Will he give the maid a second chance? Is she pregnant with her boss’ kid? It’s a gamified approach to content that the creatives involved in making these shows are well aware of: give viewers just enough of a story to make them open their wallets.

“You’re just acting for a game,” Barlow said.

Barlow is on to something considering that the payment model of microdramas closely resembles the freemium model mobile games have used for years. These platforms use their own in-app form of currency — often called coins — that viewers need to spend to unlock new episodes. Viewers get coins for watching ads, but the real trick of this system is to confuse viewers about how much money they’re spending. ReelShort, DramaBox and GoodShort use the coin model, but MyDrama — the only microdrama platform not owned by a Chinese company — does not.

“One of the things that people are concerned about with free-to-engage models and micro-transactions is that they’re a layer removed from real money, which we often have trouble keeping track of,” Amanda Cote, an associate professor at Michigan State University who focuses on video games, told TheWrap.

When it comes to freemium games, a comparable business model that’s been studied for years, roughly 5% or less of all players ever spend money on a free-to-play game, Cote said. An even smaller amount pay significant amounts of money, a user base the gaming industry calls whales. That’s who often fuels these ventures. These “whales” often demonstrate impulsivity and addictive personalities.

All four of the afforementioned microdrama platforms also offer a weekly model, but they’re steep. ReelShort is the most expensive at $19.99 a week. One year of that service would cost a viewer 380% more than a year of Netflix without ads. It’s difficult to imagine that the average American TV viewer would be comfortable paying that difference when it is laid out clearly in front of them.

For all of these red flags, the microdrama industry remains one of the few Hollywood segments that’s seen growth. As production leaves Los Angeles, microdramas serve as a stable source of income for nonunion actors and out-of-work production crews. Barlow gained a couple thousand followers from her projects and noted that her male (often shirtless) co-stars grew even more on their social media. From a consumer standpoint, these shows also fulfill a specific need for bite-sized narrative content that easily fits into people’s daily lives.

But if this trend sticks, a microdrama reckoning may be on the horizon.

“The fact that we’re able to create these films at such breakneck speeds for such low costs, it seems like a dangerous reflection of how cheap people can get hired for,” Faber said. “If we’re not advocates for ourselves and for each other right now, then we’re going to continue to be taken advantage of.”

The post Inside the Dark Underbelly of the Microdrama Phenomenon appeared first on TheWrap.