Humanity has changed an awful lot in the past 58 Years. The moon? Not so much. It was in 1968 that astronauts first drew near the moon, and it will be early this year, if all goes as planned, that a crew will return, representing a species with gadgets and abilities—and yes, problems—that didn’t exist that half-century-plus ago.

Back then, the darkest concern was that to visit the moon would be to ruin the moon. That was the way Susan Borman put it to Chris Kraft, NASA’s then-director of flight operations. a few months before the Dec. 21 launch of Apollo 8. Borman was married to Frank Borman, the commander of the mission, who would lead a crew that for the first time would leave Earth orbit and venture moonward.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Apollo 8 had two possible mission profiles: the safer one and the scary one. The safer one involved whipping once around the moon’s far side and then relying on lunar gravity to slingshot the spacecraft back to Earth. The scary one involved reaching the moon and using Apollo 8’s howitzer of a main engine to slow the ship down and settle into lunar orbit, circling the moon 10 times before coming home. The problem with the scary mission was the coming home part. If the main engine fired once to place the crew into orbit but failed to fire a second time to blast them out, the ship would become a permanent satellite—and a permanent sarcophagus—orbiting around and around and around the lunar equator long after the oxygen and fuel cells that kept the crew alive wore out. So Susan, who had no interest in being widowed by the moon, buttonholed Kraft in his office.

“If they get stuck,” she said, “you’ll ruin the moon for everyone. No one will be able to look at it again without thinking about those three dead men.”

Kraft was unmoved. He ordered up the orbital mission—and with that, the great plates of history shifted. On Christmas Eve, the crew reached lunar orbit, turned on their TV camera, and beamed back images of the ancient, ruined lunar surface to a television audience of more than one billion people—or one third of the human population. The three men—Borman, Jim Lovell, and Bill Anders—conducted a 27-minute cosmic travelogue and, at the end, on that cold, holy night, took turns reading from the Book of Genesis. When they were done, Borman concluded the show.

“And from the crew of Apollo 8,” he said, “we close with good luck, good night, a merry Christmas, and God bless all of you, all of you on the good Earth.”

That Christmas wish served as a coda—and a redemption—for a blood-soaked year that saw assassinations and burning cities in the U.S., Soviet tanks in Prague, a North Vietnamese offensive on the holiday of Tet, riots at the Democratic Convention in Chicago, and more. Borman, Lovell, and Anders received uncounted cards, letters, and telegrams when they returned, but the one that moved them most, from a woman whose name is now forgotten, read simply, “Thank you. You saved 1968.”

The still-young year of 2026 could be similarly redeemed. As soon as February 6, the crew of Artemis II will also head moonward. It will certainly not spell the first human expedition to the moon, but it will be the first since 1972—when the crew of Apollo 17 came home, the Apollo moon program was canceled, and the translunar trail went dark.

History recalls the names of Borman, Lovell, and Anders; of Apollo 11’s Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins, and Buzz Aldrin; of Apollo 13’s Lovell, Jack Swigert, and Fred Haise. It may soon recall, as well, Artemis II’s Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover, Christina Koch, and Jeremy Hansen.

Asked if he feels the weight of history as the flight draws near, Wiseman—who will follow in the footsteps of Borman, Armstrong, and Lovell as commander of the missions—at first jokes. “Until about 30 seconds ago, I didn’t,” he says. “But seriously, I really don’t think any of us have thought about that aspect of the mission. I really think we are taking the next right step in a sustained lunar presence. The important thing about being first is that there’s a second, third, fourth, and more.”

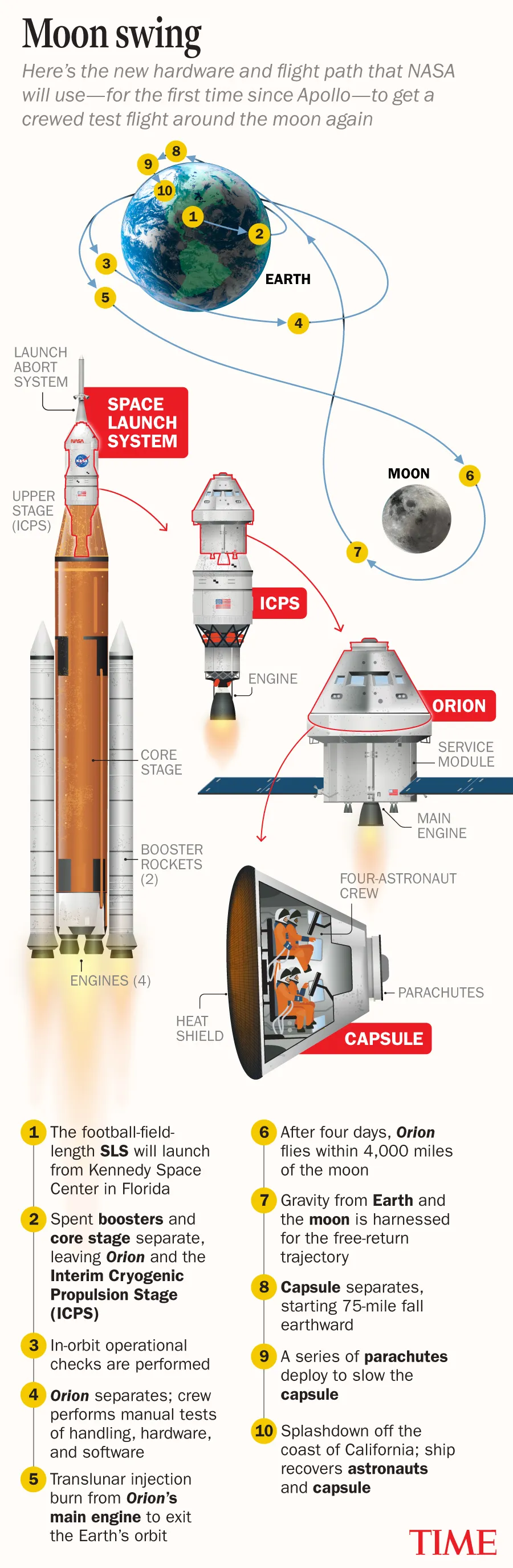

For a mission that carries so much hope, Artemis II will fly a relatively simple trajectory. After launch, it will make two long, high, looping orbits around the Earth, before pointing toward the moon, firing its engine and pulling itself away from the grip of earthly gravity. It will follow the safe profile Kraft long ago rejected, flying around the far side of the moon and coming home without a lunar orbit, to end a 10-day mission. But those 10 days will serve as a critical test for NASA’s giant Space Launch System (SLS) moon rocket and the Orion spacecraft, preparatory to lunar landings by Artemis III, IV, V, and beyond.

Artemis II will take the crew farther from Earth than any human beings have ever traveled before. The crippled Apollo 13 spacecraft flew a similar circumlunar route, reaching 158 miles beyond the far side of the moon at its most remote remove. For 56 years, that mission held the distance record, but Artemis II will smash it when the spacecraft travels a whopping 4,700 miles beyond the lunar backside. From that distance, the crew will be able to take dramatic photographs of the sphere of the Earth and the sphere of the moon in the same frame.

“I very intentionally keep myself from thinking about what seeing the far side will be like,” says Wiseman. “Because no matter what your expectation is, the reality will be different.”

Not only will Artemis II be the first mission to reach the moon in more than half a century, it will also represent a significant demographic and cultural shift. Koch will be the first woman to go to the moon, Glover the first person of color, and Hansen, a Canadian, the first non-American.

“More than a decade ago, NASA decided that equity and inclusion would be part of its core values,” says Glover. “Those decisions have led to us having an astronaut office that looks very much like America. You could reach in and grab any four people and they would look like this crew.”

“We have a lot of global stresses and problems,” says Hansen. “And those global problems require global solutions. This [including a Canadian on Artemis II] is such an amazing example of what we can do together.”

The U.S. and Canada are not the only countries that have a stake in the Artemis game. In 2020, NASA and the U.S. State Department established the Artemis Accords, a pact that has now been signed by 61 countries, binding member states to the peaceful exploration of space. Even as geopolitical alliances have been strained, the accords still stand—at least for now. Signatories are also invited to contribute modules, money, and other resources—including astronauts—to the Artemis program, with a long-term goal of establishing a permanent base near the south lunar pole, where deposits of ice can serve as an abundant source of water, rocket fuel, and breathable oxygen for astronaut residents. The widely accepted headcount of people who were in some way involved in getting Apollo astronauts to the moon is 400,000—nearly all of them American. A similar standing army, this time international, is being mustered for Artemis.

“The other day I was thinking about when we arrive at the moon,” says Koch. “And the only way I can accept that my name is in that grouping is that we’re part of a team—people who are doing the hard work.”

The Path to the Moon

The four members of the Artemis II crew will get to the moon together—at the same moment, in the same spacecraft—but they will have arrived there by very different routes. Glover’s path began in 1986, when he was 10 years old and he and his mother were waiting for a bus in Los Angeles. It was too cold for L.A., even in winter, and certainly too cold for the thin jacket he was wearing. But his mother, who was raising him alone and working multiple jobs to keep the lights on and the rent paid, could not prioritize the luxury of a proper winter coat for her son in what was usually a balmy town. So he stood at the stop as the wind cut through his jacket, watching enviously as car after car drove by, all of them looking warm, all of them looking cozy, all of them carrying lucky people who weren’t standing in the cold, waiting for a bus that would never come. And he had a thought.

“When I get out of having to live this way,” he resolved, “I will never do it again. I will never go back.”

His first step toward getting out involved studying—hard. He excelled in his elementary- and middle-school years. As a high school student he was intrigued by the sciences and enrolled in an AP biology class two years in a row—just because he loved it.

“He was brilliant,” recalls his teacher, Robin Ikeda. “He was insatiable, curious, and wide-eyed. He was super happy too. I never had anybody sign up for a course voluntarily a second time.”

When it came time for college, biology fell away and Glover studied engineering at California Polytechnic State University. After he graduated, he enlisted in the Navy and trained to be an aviator, amassing more than 400 takeoffs and landings from the deck of the U.S.S. John F. Kennedy.

But military life can exact a high price, and for Glover, the constant deployments and assignments meant time away from his wife and four daughters. In 2012 he thus made a career pivot—two pivots, actually: he applied for a Naval legislative fellowship position, seeking a yearlong job on Capitol Hill; and, at the same time, sent his résumé to the NASA astronaut program.

The fellowship came through straightaway and Glover was assigned to the office of Senator John McCain. Glover would not, however, serve his full rotation. Nine months in, he was walking through the rotunda of the Russell Senate Office Building when he noticed a missed call on his cell phone—from NASA.

“I called them back and I was on hold for like half of eternity,” Glover says. Finally, Janet Kavandi, a former astronaut and the chair of the astronaut-selection committee, came on the line—and welcomed him to the astronaut team. “The next morning,” Glover says, “she sent me an email saying, ‘It was not a dream.’” Glover, now 49, has been in space once since then, spending 168 days aboard the International Space Station (ISS) from November 2020 to May 2021.

Koch, 47, made her way to NASA via the South Pole. When she was a child, her dual fascinations were Antarctica and space, and the walls of her bedroom were covered with posters and maps of both. “If anyone within a country mile said the word Antarctica, I was all over it, asking ‘How can I get there? When can I go?’” she says.

Born in Grand Rapids, Mich., she relocated to North Carolina State University to study electrical engineering and physics. In 2002, with those twin degrees in her pocket, she applied to and went to work for NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., assigned to a team designing spacecraft instruments.

But after two years there, Koch gave in to her Antarctic itch, applying to become a research associate in the United States Antarctic Program. She spent the better part of three years in Antarctica, including a year-long stay at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. Even with a handful of other researchers to keep her company, the isolation was challenging, the work demanding, and the elements absolutely punishing. During one especially frigid spell, the temperature outside the team’s small habitat fell to -111°F.

In early 2013, having ticked her Antarctica box, Koch turned back to her other great passion and applied for admission to NASA’s 21st astronaut class. The interview process was long; finally, in June, she got a call from Kavandi. “We’re calling to tell you to join our team,” Kavandi said. “We want you to come to Houston.”

That call led to a whopping 328-day stay aboard the ISS from March 2019 to February 2020—a record that still stands for longest single spaceflight by a woman. During the course of that station rotation, Koch also participated in the first all-woman spacewalk, along with astronaut Jessica Meir. The event was a milestone that generated much buzz on Earth. Then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi took to what was at the time known as Twitter, applauding Koch and Meir “for leaving their mark on history.”

Hansen, 49, the Canadian, has yet to make that mark. The only rookie in the Artemis II group, he comes to space via a farm in Ailsa Craig, Ontario, where he lived as a child, going to school during the day and helping with chores in his off-hours. But much of that time, his mind was on flying. From an early age he knew he wanted to become a pilot and join the military. When he was 12, his father helped him enroll in the Royal Canadian Air Cadet Squadron, a youth leadership program that trains boys and girls ages 12 to 18 to fly while they go to school, and promises to get them behind the stick of a glider in their first year in the corps.

“It has a loose military affiliation,” Hansen says. “You wear a uniform, you polish your boots, you drill—and you do get to go flying.”

Hansen had his glider license by age 16 and his private pilot’s license the next year. Upon graduation from high school, he enrolled in the Royal Military College Saint-Jean, where he ultimately earned a master’s degree in physics. He joined the Royal Canadian Air Force, and was eventually assigned to the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD), patrolling the skies over the Arctic.

In 2008, the Canadian Space Agency opened its books for its astronaut team. Hansen applied and the next year got the nod. He has spent the past 17 years training for a mission—any mission—and at last, on April 3, 2023, he got the call that he had been tapped for the moon.

“He came home in a celebratory, excited mood,” recalls Hansen’s wife Catherine. “He said, ‘It’s happening, it’s official. All that we had hoped for is coming true.’”

Wiseman, 50, the mission commander, earned his path to the peaceable moon in part by serving the war-torn Earth. A graduate of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and Johns Hopkins University, where he earned first a bachelor’s degree and then a master’s, both in systems engineering, he was commissioned as a Naval aviator in 1997 through Rensselaer’s Reserve Officers’ Training Corps program. He became a flier at a dangerous time, serving before and after the Sept. 11 attacks and throughout long stretches of the war in Iraq, completing five deployments.

The combat missions he flew sit a bit uneasily with him today. “I shouldn’t say I didn’t like it,” he says, “[but] I don’t ever need to do that again. I didn’t like it for the people on the ground. They didn’t like it for us in the air. I definitely scared the sh-t out of myself sometimes.”

In 2008, Wiseman changed directions. Along with 3,500 other hopeful applicants, he submitted his name for selection as a member of NASA’s 20th class of new astronauts. The next year, nine of them, Wiseman included, were selected. He has since flown a 165-day space station rotation, in 2014; and from 2020 to 2022 he served as head of the NASA astronaut office.

“There was never a launch where I didn’t think I was on the verge of a heart attack because you know the careers you’ve assigned to the mission,” he says. “You’re thinking about their success, their family, how they are doing. I spent a lot of time agonizing over every little thing.” Come February, when the engines light on the SLS rocket, the people on the ground will be feeling that for Wiseman and his crew.

How they’ll get there

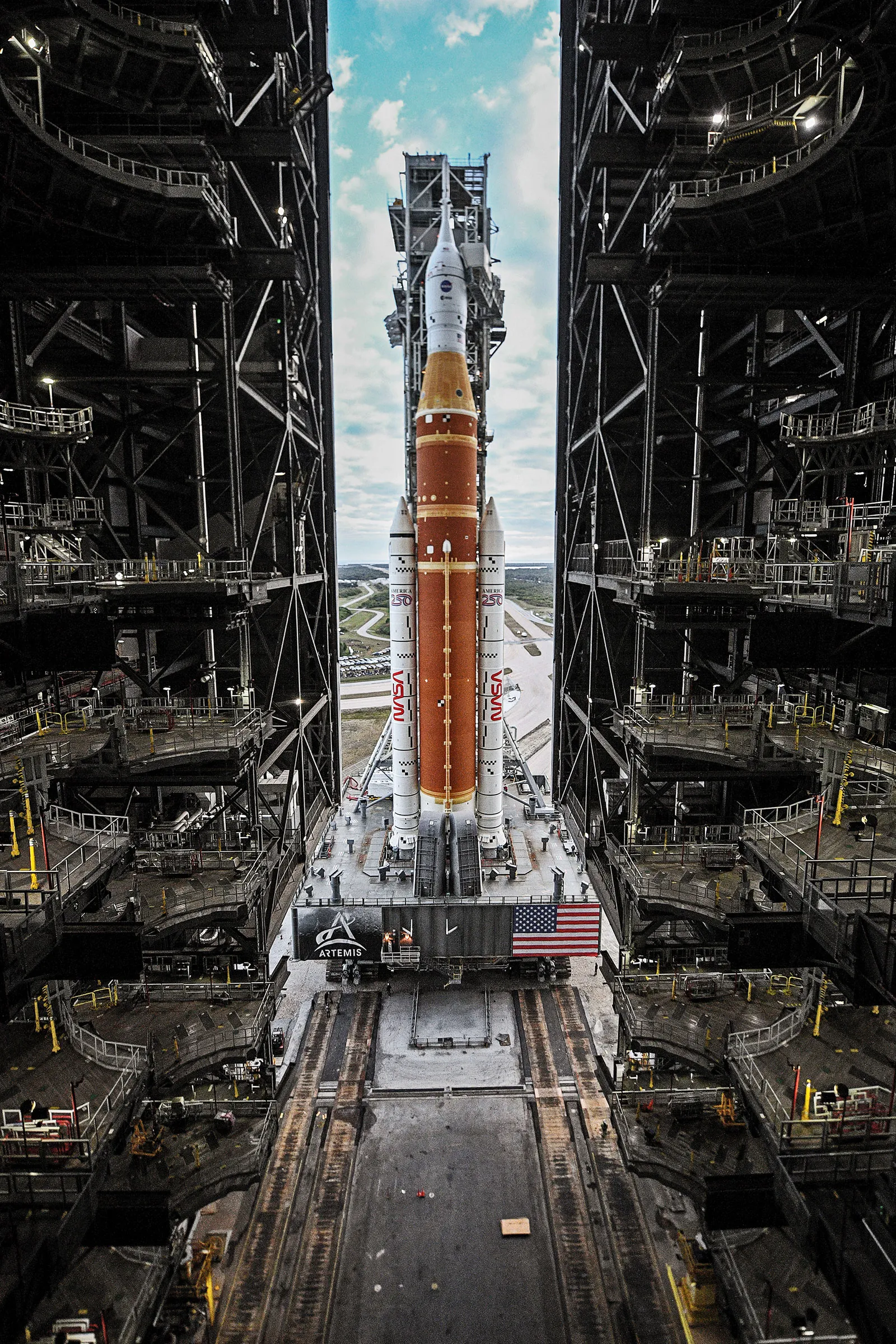

Artemis II’s journey to the moon will by no means follow an as-the-crow-flies trajectory. The mission will begin when the six first-stage engines of the SLS moon rocket ignite: four liquid-fueled and two strap-on solid-fuel rockets. Since 1968, the most powerful rocket ever to lift humans has been the Apollo program’s Saturn V, which put out a literally ground-shaking 7.5 million lb. of thrust. The SLS produces a staggering 8.8 million lb.

On its upward climb, the SLS will quickly exhaust the fuel in all six of its first-stage engines, and they will be jettisoned, leaving only the rocket’s upper stage and the Orion spacecraft to reach orbit. That orbit will be a lopsided one, with a low point, or perigee, of 115 miles and a high point, or apogee, of 1,400—far higher than the 250-mile altitude at which the ISS flies.

After one 90-minute sprint around the Earth, the still-attached upper-stage engine will fire, raising the orbit to 1,500 miles and an apogee of 46,000 miles—an altitude that takes the spacecraft about a fifth of the way to the moon. At that speed and that altitude, the ship needs a relatively small push to break free of Earth orbit and head moonward—a maneuver called translunar injection (TLI). That critical step will occur after one more orbit around Earth, when Orion jettisons the upper stage and relies on its own smaller service module engine to give it the kick it needs to soar out to the moon.

It will take about four days for the ship to cross the total 244,000-mile void between Earth and the moon. The crew’s closest approach to the moon’s surface will be about 4,000 miles above the lunar peaks, increasing to its record-breaking distance of 4,700 miles on the far side, before lunar gravity slingshots the ship back to Earth on another four-day journey.

The final leg of the trip, reentry into Earth’s atmosphere, will take some fancy flying. Spacecraft reentering from Earth orbit tap the brakes of their retro rockets to reduce their 17,500 m.p.h. speed, causing them to fall slowly from the sky and ease their way into the atmosphere. Artemis II will instead slam into the atmosphere at a speed of 25,000 m.p.h. Both styles of reentry are fiery. As an Earth-orbiting spacecraft descends, temperatures of up to 3,500°F bloom across the heat shield at the bottom of the capsule. The faster-moving Orion spacecraft will have to endure a blistering 5,000°F—half as hot as the surface of the sun.

To make that reentry survivable, Orion will not descend on a relatively straight trajectory the way an orbital ship does, but will instead fly a so-called skip-entry path, entering the atmosphere, climbing back into space, and then reentering, bleeding off heat and gravitational forces along the way. That roller-coaster ride was perfected on Apollo 8, and was used successfully on each of the other eight lunar missions that followed. Still that does not mean the exercise won’t be hair-raising for the crew of Artemis II. Asked about the larger meaning of the 10-day mission, Glover focuses instead on the last minutes of the last day.

“Let’s get to splashdown successfully,” he says. “Then maybe we can revisit the question.”

The next steps

It won’t be long after splashdown that another pressing question will be on everyone’s minds: What comes next? Artemis II is what space planners call an engineering mission, one intended less to explore than to test all of the spacecraft’s on-board systems—propulsion, navigation, life support, computer, guidance, communications, and more. It will also test the mettle of the crew in space, the launch team in Florida, and the mission controllers in Houston. There are a lot of cobwebs for NASA to shake off after a 54-year hiatus between lunar missions.

Officially, the next mission, Artemis III, will handle the very big job of landing on the moon. Officially too, that will happen by 2028—but few people believe that goal is achievable. The target date has slipped repeatedly, from 2024, to 2025, then September of 2026, and then mid-2027. At the moment, the biggest problem concerns the lunar landing craft—which, inconveniently, does not exist.

Like the Apollo crews, future Artemis astronauts will rely on two vehicles to execute a lunar landing: a mother ship to orbit the moon and reenter Earth’s atmosphere and a lander to take two of the four astronauts down from orbit to the lunar surface. In 2021, NASA awarded Elon Musk’s SpaceX the contract to build the lander and cut the company a $2.89 billion check to get the work done.

In the Apollo days, the lander and the mother ship were launched on the same rocket. Today’s larger, more capable lander will be launched separately, on a different rocket from the SLS, and dock with Orion in space. The rocket SpaceX proposes using is its massive Starship, with the upper stage of the vehicle configured as the lunar lander. From the beginning, it was an improbable choice. The Apollo lunar module stood 23 ft. tall, weighed just 32,500 lb.—flyweight as spacecraft go—and had a splayed, four-legged stance that gave it a low, sure-footed center of gravity. The Starship lander, by contrast, is a silvery silo, weighing 200,000 lb. and standing 165 ft. tall, requiring an onboard elevator rather than a ladder to get the astronauts down to the ground. Once it’s launched it won’t fly straight to the moon, but rather will loiter in Earth while up to 20 fuel tankers are launched to gas it up before it leaves.

That’s a lot of machine for an already complicated job—and it hasn’t helped that Starship rockets have repeatedly exploded or crashed on multiple launches over the past three years, pushing the project far behind schedule. The delay has been especially concerning to lawmakers and space planners in the face of China’s expressed goal of landing astronauts on the moon by 2030—kicking off a 21st century reprise of the old U.S.-Soviet space race.

“[The Starship] architecture is extraordinarily complex,” former NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said during Senate testimony in September 2025. “It, quite frankly, doesn’t make a lot of sense if you’re trying to go first to the moon, this time to beat China.”

By last October, then acting NASA Administrator Sean Duffy had seen enough. “I’m going to open up the contract,” he said in an appearance on CNBC. “I’m going to let other space companies compete with SpaceX. We’re going to push this forward and win the second space race against the Chinese.”

Musk responded … colorfully. “Sean Dummy is trying to kill NASA,” he posted on X. “The person responsible for America’s space program can’t have a 2 digit IQ.”

But SpaceX quickly fell in line. In November, the company posted a lengthy update on its website, describing the R&D milestones it has already achieved on the way to completing its Starship lander, and offering reassurance that work on the project was indeed proceeding apace. At the same time, Blue Origin, the space company owned by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, submitted a proposal to NASA that included plans for its Blue Moon Mark 1 lander, a vehicle that is supposed to have an uncrewed test flight to the moon atop Blue Origin’s New Glenn rocket sometime this year. Also in the hunt is Lockheed Martin, the prime contractor for the Orion spacecraft, which is proposing an accelerated plan to build a lunar lander cobbled together from hardware already in existence.

“We call it design for inventory,” Rob Chambers, Lockheed’s senior director for human spaceflight strategy, told TIME in October. “We’re sitting down with industry partners and saying not ‘What part can I order out of your catalogue?’ but ‘What serial number exists today?’—even if it’s on another spacecraft.”

All of that, however, is for later. For now, the focus is on Artemis II. A return to the lunar neighborhood will not only represent a significant—if temporary—edge in any space race that does exist with China, but also offer a kind of public uplift that, since the 1960s, space flight has uniquely been able to provide. Not every mission, of course, touches the collective soul, but some do: John Glenn’s three orbits of the Earth in 1962; Apollo 8’s Christmas Eve lyricism; Apollo 11’s lunar landing; Apollo 13’s hair’s-breadth rescue—all were less American experiences than global dramas, global triumphs, global joys.

In 2019, Collins—the command-module pilot for Apollo 11, who station-kept aboard the orbiting mother ship while Armstrong and Aldrin flew down to the surface and pressed the first boot prints onto the moon—spoke to TIME about the international reaction he experienced when the crew toured the world after their return.

“I thought that when we went someplace they’d say, ‘Well, congratulations. You Americans finally did it,’” Collins recalled. “And instead of that, unanimously the reaction was, ‘We did it. We humans finally left this planet and went past escape velocity.’”

Of the 24 lunar astronauts who did the leaving from 1968 to 1972, only five, all in their 90s, remain. With Artemis II, the lunar ledger will at last be reopened and four more names inscribed—a fine and fit crew who will be sent into the cosmic deep as emissaries of the 8.3 billion of us who will remain forever earthbound. Apollo 8 saved 1968. Artemis II may work similar magic today.

The post Astronauts Are Going Back to the Moon For The First Time in Half a Century appeared first on TIME.