As artificial intelligence pushes into Hollywood, one name has become a symbolic target for the reservations artists have about the evolving technology: Tilly Norwood.

Created by Eline Van der Velden, a former actress, through her company Particle6, the A.I. “star” has reportedly been courted by talent agencies.

Divisive, to say the least, Tilly has created a split in the industry between those eager to embrace the technology and its promise of easier, faster productions, and those concerned about the ethical implications of an avatar taking opportunities from human talent.

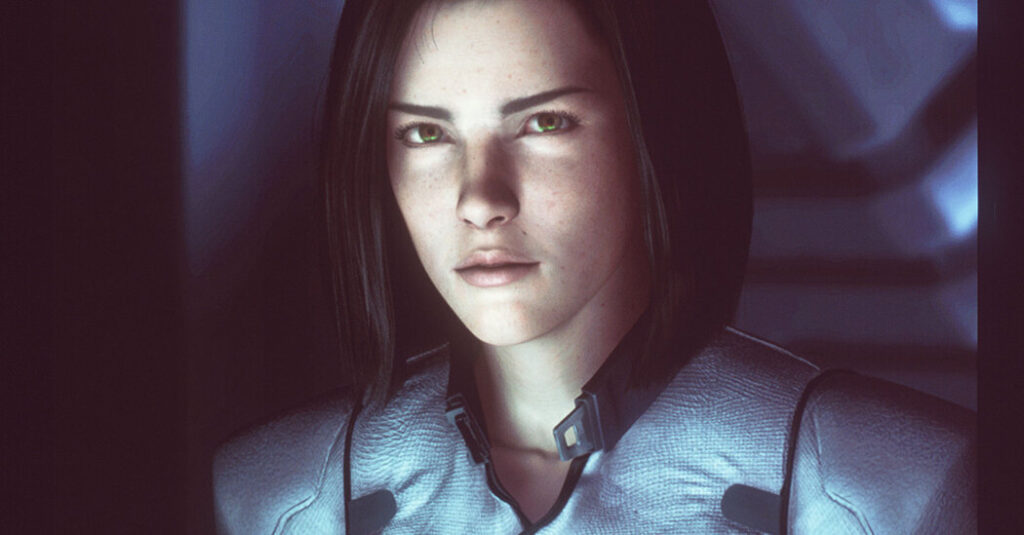

But long before Tilly, a different photorealistic character provoked similar fears. Aki Ross, the heroine of the 2001 sci-fi adventure “Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within,” was considered at the time to be the first digital actress.

“Seeing how people are reacting to A.I., it was the same feeling I had 25 years ago,” said Roy Sato, who worked as the lead animator on Aki. “We had this hyper-realistic computer graphics actress, and people were like, ‘Am I going to be replaced? Am I outdated?’ It’s a funny parallel that 25 years later it’s happening again.”

Sato joined Square, the Honolulu-based studio behind the film, in 1997 after working as a hand-drawn animator for Disney. “Everything was so new back then. We had Pixar with ‘Toy Story,’ but there was no hyperreal C.G. human animation for movies at the time,” Sato said. “We were all trying to figure it out.”

Unlike what’s possible with today’s advancements, in the early 2000s a tool like facial capture was nonexistent, which meant that Sato had to painstakingly animate Aki’s expressions. He used the actress Ming-Na Wen’s voice performance as inspiration. For the rest of the body, motion capture was already in use, so another performer helped create reference material for Sato.

Wen’s audio also helped drive the body performance, with the motion-capture actor miming to the dialogue. From there, Sato had to figure out the details based on the shot size: The closer the shot was to the face, the more work Sato had to do to sell that performance.

In effect, one character required the talents of three people. “Even though everything was done on a computer, it felt very handcrafted,” Sato added. “If it was like A.I. where it was just completely generated by computers, I think it would be pretty cold. The human element would be gone.”

Initially the filmmakers, including Hironobu Sakaguchi, creator of the “Final Fantasy” video game franchise and director of “The Spirits Within,” had big ambitions for Aki Ross.

“Sakaguchi-san was hoping that there’d be sequels and she’d be starring in them,” said Andy Jones, the film’s animation director, “and there could also be spinoffs or advertisements if it was a bigger success. That was something that was exciting to the team. We had created a kind of virtual star at the time.”

Sato became aware of this only toward the end of production as publicity efforts for the release ramped up. “I didn’t see Aki as an actress,” he said. “It was like, we just have a C.G. character — and that’s it.”

Still, Aki Ross appeared on magazine covers, and was even featured in the men’s publication Maxim, for its “Hot 100” issue in 2001. (Aki was ranked No. 87.) Entertainment Weekly referred to her as an “It Girl.”

“At the time they were saying, ‘That’s the ideal movie star because it doesn’t age,’” Jones recalled. “‘You can use it for years and years and years, and it’s always the same age.’”

In promoting Aki in the press as a quasi-human entity, the marketing team aimed to highlight the boundary pushing technology, not the character itself. Putting Aki in a swimsuit for Maxim served as a gimmick to demonstrate the photorealism that animation could achieve at the time, not only to create backgrounds, but human characters as well.

Jones remembered that the main question journalists had about “Final Fantasy” was whether the technology would replace actors. “I thought it’d just coexist,” he recalled thinking. “She’s like any other star, but she’s got a special thing because she’s virtual. And that still exists today,” as with popular Japanese virtual idols, the digitally conceived music performers that engage with their audience online.

Then, as now, the discussion surrounding an intangible actress could go in uncomfortable directions: “I don’t know if it was a joke or not,” Sato said, “I just remember hearing someone say, ‘With a digital actor or actress, you can just tell them exactly what to do and, they won’t argue.’ It’s a sad thought. You’re just telling something to do something, and it’ll do it.”

But the filmmakers’ plans never came to fruition. Critics were not won over — in The Times, Elvis Mitchell wrote of missing “the unpredictable physical chemistry of actors that computer science hasn’t mastered” — and the movie’s box-office results were lackluster. “The Spirits Within” grossed $85.1 million worldwide on a budget of $137 million.

As the producer Chris Lee explained, the inflated cost was tied to building an entire studio from scratch in Hawaii. “So much of that money was spent literally doing everything from the physical buildings to coming up with new computer banks,” Lee said.

For Jones, who went on to win an Oscar as part of the visual effects team on James Cameron’s first “Avatar” movie, Aki served as a foundational development that ultimately led to technology that allowed Cameron to create his Na’vi saga.

The human component remains, however.

Even on the first “Avatar,” several years after “The Spirits Within,” facial capture was still new, which meant animators had to perfect the expressions to make them believable.

“They’re the digital side of a makeup or a hair team, who are just making sure that performance is coming onto the screen,” Jones explained. “It still takes a team of people, but the actual driving force behind the performance is the actor.”

While Aki helped paved the way for the pipeline of hyperrealistic characters, what they could do back then was limited, Jones admitted. “If you look at Aki, she still looks fake,” he said. “We could only render so many hairs and deal with the way light interacts with them. A.I. now gets that stuff right out of the gate.”

Though Jones said he was fascinated with where the technology is going, he cautioned that creating nuanced performances is still a challenge for generative A.I.

“Tools are getting better, but I still think that to craft these performances in the right way, you’ll still have to have a human behind it who’s either directing it or prompting it to a very specific place,” Jones said.

Even then, he argued, as A.I. transforms entertainment, actors and actresses will still be essential because the choices human performers “make that are just so believable and natural” can’t be easily crafted with prompts. “I don’t think it’s even possible, actually,” he added.

The post Before Tilly Norwood, This C.G.I. Actress Was Considered an ‘It Girl’ appeared first on New York Times.