“Now what I’m asking for is a piece of ice, cold and poorly located,” said President Trump in Davos last week. His knowledge of Greenland may be incomplete (several times he seemed to confuse the territory with Iceland, its sovereign neighbor), but his metaphor of the territory as depopulated: well, that is more familiar.

Even if the president of the United States seems to have backed down from threats of annexation, American belligerence toward Greenland has altered all our futures. “The old world order is now gone,” as Denmark’s prime minister told The New York Times. But who will feel the impact first, and how? When it comes to the people most affected by this geopolitical tragicomedy, and still living in fear of a military invasion, our perspective on the world’s largest island is as distorted as the Mercator projection.

As it happens, there is an exhibition of Greenlandic art — a fantastic one, an exhibition of youth and beauty and resignation and rebirth — in New York at MoMA PS 1 in Queens. Inuuteq Storch, a 36-year-old photographer, has been gazing since his teenage years at the joys and mundanities of young and old alike, and picturing everyday life in a little-known territory with lyricism, wit and a fair amount of melancholy.

“Soon Will Summer Be Over,” reads the exhibition’s title, with its wistful anastrophe — and the winter, every Greenlander knows, will be long and dark. But there is so much to see before the sun sets, and Storch’s casual intelligence and profound humanism make him a voice of our time. This show is simply (but not so simply) about what it means to be alive today, on the edge of the world and, all too suddenly, at its center.

I initially saw Storch’s work at the 2024 Venice Biennale, where he was the first Greenlander (and first photographer) to represent Denmark; at that pavilion’s entrance, over the chiseled name of the colonial power, the artist superimposed the words “KALAALLIT NUNAAT,” Greenland’s domestic name. In a year when the Biennale took a dewy-eyed (and, as I wrote at the time, neocolonialist) view of Indigenous creativity, Storch struck me as a rare, candid example of an artist committed to representing a population as it actually lives today — amid new technologies and old traditions, between rival languages and among conflicting histories, passionate (sometimes) and bored (frequently). In other words, just like most people.

His photographic project has a dual aspect: raw, sometimes romantic pictures taken across the island, combined with a fascinating archival mission to preserve Greenlanders’ vernacular photography and home cinema. Yet his photography makes no great show of its decolonial chops. He focuses on the usual, the modest. What’s fleeting. What melts.

Storch was born in 1989 in Sisimiut, Greenland’s second largest city (population 5,600, and inhabited for more than four millenniums), though he’s no stranger to New York; he studied at the International Center of Photography here, as well as at a Danish photo academy. Returning to the west coast of Greenland, he shot his breakthrough series, “Keepers of the Ocean” (2019), which fills two galleries at MoMA PS1 with frank, free observations of the town where he grew up.

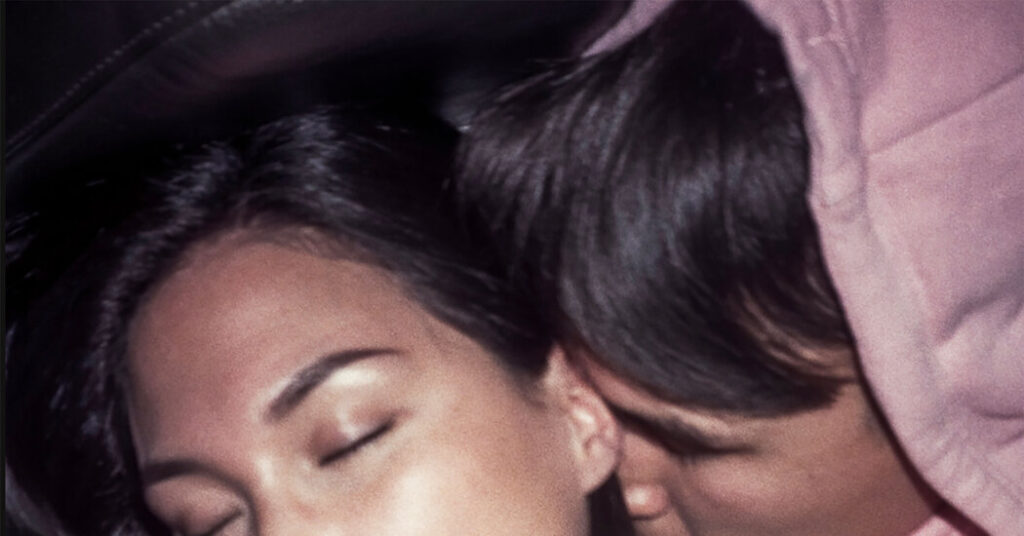

A young woman holding tight to her sled dog on a leash, two lovers in hoodies, a moped by the bay: These quotidian sights established that his home was neither terra nullius nor Inuit utopia, and gained distinction from his use of richly grained analog film and slow exposure times. In one photo of a metal transmission tower during a nighttime snowstorm, the flakes are so big they appear as giant white pixels. As if the snow were redacting the sky.

Larry Clark, photographic bard of American skateboarders on the prowl, came to mind as I examined Storch’s shots of young Greenlanders drunk among the daffodils, or smoking and taking cameraphone videos in a bright yellow pickup truck. Wolfgang Tillmans, too; Storch finds an everyday poetry in an anorak and ski pants, turned by his camera into a classical drapery study. But unlike those fashion-oriented photographers, Storch has a less sentimental eye and a keener social sense.

Importantly, Storch in Sisimiut turned his camera to the old as well as the young. The teenager blissed out among the Arctic flowers is not the only drunk; an older man, beer bottle at his side and pipe in his mouth, points with both fingers to the sky with a beatific grin. Another older man, sprawled on a sofa, wears a T-shirt blaring the word “DUBAI” and festooned — why not, up north? — with palm trees.

Youth, angling for Storch’s lens, is no springtime anyway. The young Greenlanders he photographs find love and also heartbreak; they contend not only with alcoholism but also with high unemployment and a shockingly high suicide rate (sadly not unique, among Indigenous communities in our hemisphere). In the summer of 2023, Storch traveled to Qaanaaq, close to being the northernmost human settlement on Earth — and built from scratch in the 1950s after the United States forced Greenlanders to relocate from an Air Force base. The impact of colonial domination, of Danish rule and American commerce, appears all over these polar pictures. The houses are ramshackle in this poorest region on Greenland, with mass-market prints of Jesus and Mary on the walls.

But the young of Qaanaaq are free: sunbathing in a place with no night between April and August, while men butcher seals by the harbor. Storch declines to name his subjects, or to give his prints titles, lest we mistake his cool gaze for a new ethnography, and he is not afraid of a personal gesture. In one of the funniest prints in this show (but it is a tragic humor), he greets a huge, vertical glacier front in Qaanaaq — a region of the world most severely affected by climate change, where houses are sinking into the permafrost — with a heavy-metal rock-on gesture: one of numerous shots where Storch’s body or shadow is partly visible in the frame.

One evening in Sisimiut, while still a teenager, Storch and his friends were dumpster diving. In the trash he found several canisters of old film, and when he developed them he discovered rare documents of Greenlandic life taken by its native inhabitants, rather than the Danish documentation that typified the look of the past.

Since then, Storch has devoted himself to resuscitating old Greenlandic snapshots and home movies — and in “Anachronism,” a masterfully edited and deeply moving two-channel video at PS1, he proposes a found-footage reconstitution of the years before and after the territory won home rule in 1979. He shows us kids on a swing set at midcentury, and low-slung, unlovely postwar housing against the mountains. We witness a wedding, and then a seal gutting. The future Queen Margrethe II visits, sometime in the early 1970s, wearing a traditional Greenlandic beaded collar and greeting cheering crowds; later, schoolchildren pull a Danish flag down from the pole and start to dance. In the score we hear whistling, a plangent detuned piano, and also a Lutheran psalm. What is lost can yet be found again, though it will not be what it was before; the icebergs, bigger back then, appear through the nostalgic dye shifts of film decades old.

The first quarter of the 21st century was a time of aging. “The past devours the future,” as the French economist Thomas Piketty had it; aging populations, aging economies, an aging culture. But in this bewildering new world we are all young again — trying to grasp a changed order for which no historical models seem to be a guide. At the end of “Anachronism,” Storch projects the propellers of a U.S. Air Force plane, flying over the high Arctic tundra, in two mirror images: a bewildering sight. The two propellers look like a moth’s wings. The clouds below look like ice floes. In the distance is a sun that will not set for months.

Inuuteq Storch: Soon Will Summer Be Over

Through Feb. 23, MoMA PS1, 22-25 Jackson Avenue, Queens; 718-784-2086, momaps1.org.

Jason Farago, a critic at large for The Times, writes about art and culture in the U.S. and abroad.

The post Alive on the Edge of the World, and Suddenly at Its Center appeared first on New York Times.