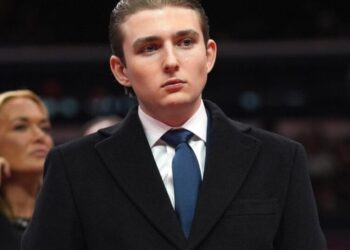

Federal agents have stopped, detained or violently confronted dozens of American citizens in Minneapolis in recent weeks under suspicion of being undocumented immigrants or for protesting the government’s crackdown. But the detention of Sophie Watso stands out.

It’s not because of the basic circumstances. Like many residents of Minneapolis, the 30-year-old artist was tracking agents and sounding her horn and whistle when, video shows, she was boxed in by law enforcement vehicles in front and behind her 2011 white Ford Ranger. Nor was the manner of her apprehension unusual. When the agents refused to identify themselves, she said, she refused to produce identification, and they proceeded to do what has become common — shattering her driver- and passenger-side windows, dragging her out, wrestling her to the ground and applying handcuffs.

The distinguishing irony of Ms. Watso’s detention is that she is Native American, from the Mdewakanton Dakota tribe. She and other tribal members are alone among the many players in the immigration operation — the Washington architects, their agents on the streets and their targets — in having a legitimate claim to possessing no immigrant blood.

That irony was only magnified as she rode zip-tied in the agents’ S.U.V. to the Bishop Henry Whipple Federal Building, the headquarters of the immigration operation and the lockup for those detained.

The federal building is on the vast expanse of government property at the convergence of the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers, land that is the site of the Dakota tribe’s origin and the center of its spiritual world. It is also the location of Fort Snelling, where 1,600 Dakota were held in deadly conditions after the tribe’s 1862 uprising over its treaty dispute with the government. Thirty-eight men identified as ringleaders by the Lincoln administration were publicly hanged in the largest mass execution in the country’s history.

As Ms. Watso was being driven there, she sang a Native song of hope and healing. “I knew where I was going my ancestors were there,” she said. “I wanted them to hear me.”

History is resonating loudly for Minnesota’s large Native American population as the Trump administration carries out its aggressive, sometimes deadly, crackdown on immigrants deemed ineligible to live in the United States and citizens challenging the operation. The word “occupation,” the preferred term local officials and residents use to describe the civic war they are fighting against the federal government, strikes deep historical tones for many in the Indigenous community.

“As Native people, we’re pretty accustomed to fighting the federal government going back 530 years since they landed with their ships,” said Rachel Dionne-Thunder, vice president of a local group called the Indigenous Protector Movement. “It just so happens that everyone else is waking up to it.”

Ms. Dionne-Thunder has been spending her days at the Pow Wow Grounds cafe, which has become a very crowded base of operations for many in Minneapolis’s Native American community during the crackdown.

A squat yellow building with murals depicting Native American gatherings, it is located on a stretch of East Franklin Avenue known as the American Indian Cultural Corridor for its collection of community organizations. On Jan. 9, Ms. Dionne-Thunder was confronted just a block from Pow Wow Grounds by agents whose activities she was following. Agents let her go after being persuaded she was a citizen, but not before her husband, Vinny Dion, had an exchange with one of them.

In the exchange, recorded on video and confirmed by two other witnesses, Mr. Dion said: “This is Native land. Why are you messing with us?” The agent replied: “I’m a native, too — I’m from here,” and before driving off said he was going to “stay right here, bro.”

Native Americans are not a stated target of the crackdown, but their complexion has gotten them caught in the dragnet. In a September Supreme Court ruling, Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh wrote that while “apparent ethnicity” alone was not sufficient reason for agents to make an “immigration stop,” it could be a “relevant factor.” On the street, said Ms. Dionne-Thunder, that legalese often seems to be translated as, “They see a person of color and grab him.”

Jose Roberto Ramirez, a 20-year-old born and bred Minnesotan and son of a Native mother, was stopped while driving just north of Minneapolis on Jan. 8, the day after another American citizen, Renee Nicole Good, was shot and killed by federal agents. He saw agents in an S.U.V. appear behind him, turn on their flashing lights and pull up their masks, according to his aunt, Nakia Buck. Mr. Ramirez called relatives when he realized what was happening. Ms. Buck’s sister arrived and pleaded that they were “Hispanic and Native.” Ms. Buck said the agent responded flatly: “Not with that name.”

As agents detained Mr. Ramirez, his aunt said, they hit him, leaving welts on the back of his head. The family produced his birth certificate, and he was released after six hours at the Whipple building. But on Monday, the family was accompanying him to federal court, where he was facing a hearing on an arrest warrant. The charges? Assaulting, resisting and interfering with a federal agent.

In an affidavit, a federal agent said Mr. Ramirez had tried to flee agents and struck one “on the right eye with a closed fist.” According to the affidavit, the encounter started when agents were pursuing an “Ecuadorean national with a criminal history.” Mr. Ramirez, the affidavit said, “matched the description of the target subject.”

A lawyer helping Mr. Ramirez, Chase Iron Eyes, who came from North Dakota to give legal assistance to Native Americans after Ms. Good’s killing, is one of a few lawyers who have been a frequent presence at Pow Wow Grounds.

Free legal advice is only one of the additional services now added to the cafe’s usual offerings of coffee, soup, burritos and fry bread. Now the cafe, with the adjoining “All My Relations Gallery,” is a source of packaged food and supplies for delivery to people too worried to venture out on the street, tribal IDs for those needing citizenship documentation and cold-weather supplies for “observers” tracking ICE activity. “Organized chaos,” says its proprietor, Bob Rice, a descendant of the White Earth Nation. Over the last week or so, he said, he has prepared 140 gallons of coffee, 100 gallons of soup and 1,000 pieces of fry bread.

In the parking lot, a robust fire has roared nearly around the clock, warming a clutch of tribal members, including some who came from around the country in solidarity and have slept in tents despite the subzero temperatures.

Inside the cafe, the conversation flows between wounds past and present with hardly a transition. “I’m part of three traumatic events,” said Phil Little Thunder Jr., 68, a Lakota tribe member who had traveled from South Dakota.

One ancestor, he said, was among those hanged in the 1862 mass execution. His great-great-grandfather was chief of the Lakota Sioux village attacked by U.S. forces in 1855 in what is known as the Battle of Blue Water. And ancestors of the mother of his children were killed in the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre of Lakota tribe members by the Army, for which Congress eventually expressed “deep regret.”

To him, there is little mystery why the current immigration action triggers past traumas for his people. “You give someone power and they go out of whack,” he said.

The Pow Wow Grounds is across the street from the original headquarters of the American Indian Movement. The movement, founded in 1968 as an ardent proponent of Native American rights, was seen as a national security threat by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and engaged in a deadly 1973 standoff with the government at the site of the original Wounded Knee Massacre. The original impetus for its founding was combating discrimination in Minneapolis, and one of its original projects was establishing patrols to monitor police abuse against the Native population.

Nearly 60 years later, the crew at the Pow Wow Grounds is part of the effort to monitor ICE enforcement across Minneapolis. “The federal government, they’re going after brown people,” said Mr. Rice. “Our neighbors are brown people. A lot of us are brown people.”

That was part of the motivation for Ms. Watso, who had moved back to Minneapolis just over two years ago to deepen her connection to her heritage on ancestral land. She said she could not sit out the confrontation over the federal action. “This is not something we get to watch,” she said. “This is something we have to be engaged with.”

On the day of her encounter, she said, she saw the agents’ S.U.V. by chance and began tracking it, sounding her horn and whistle. “My intent was to follow them and to warn people of their presence,” she said.

At the Whipple building, she was brought to a holding area and given a receipt for her belongings, the only record of her detention, which she showed to The New York Times. “It was just a room full of brown people,” she said. She was then led to a cell with a Somali woman and later transferred to a jail in a neighboring county before being brought back to the Whipple building a day later, where she was released without any charges being filed.

But there was one final insult for Ms. Watso on her ancestral land. An officer told her to exit through the front door and make a left to the parking lot, where she expected to be picked up by her mother and others. But she said she made a left too abruptly and ended up in the parking lot for government vehicles. Suddenly, she was wrestled to the ground, zip-tied again and brought back into the Whipple building. “That was the most traumatic part of the whole thing,” she said, recalling the scene of agents who had just released her confronting agents who had just tackled her.

“They said, ‘She jumped the fence — she’s trespassing,’ ” she said. “They lied.”

She was set free again, but the fear lingers. “It’s a feeling of being scared in your own skin,” she said. (The Department of Homeland Security did not respond to an email seeking comment.)

One of many moments from her trip to Whipple sticks in her mind: An agent, noting that her driver’s license listed her address as outside the city, said: “You’re not even from Minneapolis. Why do you care?”

“This is Dakota land,” she recalled saying. “I’m Dakota.”

The post For Minneapolis’s Native Americans, a New Fight Echoes a Bitter History appeared first on New York Times.