As high school teacher Christa McAuliffe prepared to be strapped into the space shuttle Challenger, Brian Russell, an official at the company that built the craft’s solid rocket boosters, had just participated in a fateful teleconference from his Utah headquarters.

Like every other engineer in the conference room at Morton Thiokol on that day four decades ago, the 31-year-old Russell opposed launching because the bitterly cold temperature at Florida’s Kennedy Space Center threatened the O-rings that sealed the rocket boosters. Their managers initially supported this view, but Russell listened in dismay as they reversed themselves under pressure from NASA officials and senior company officials and signed off on the launch.

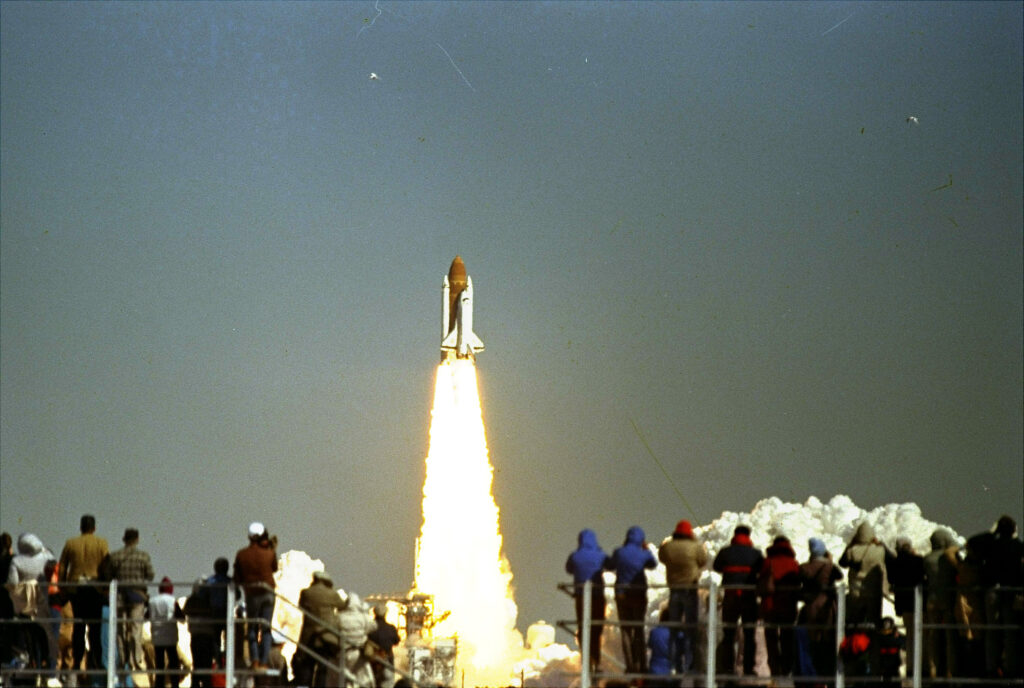

The mission ended in catastrophe for the reason that Russell feared — a story I know well as a reporter who covered McAuliffe and witnessed the Challenger’s explosion. But for those involved in this tragedy, the families of the astronauts and those who approved the launch, much about this story is perhaps even more relevant today than it was on Jan. 28, 1986.

The belief that there are still lessons to learn from the disaster is what led Russell last year to take an extraordinary step that, until now, has received no public notice. He visited NASA centers across the country, telling the Challenger story in hopes that similar mistakes will not occur as the space agency prepares to launch four astronauts on Artemis II, which is scheduled to fly by the moon as soon as February.

The lesson of Challenger is not just about the O-rings that failed. For Russell and colleagues who accompanied him on the NASA tour, understanding the human causes behind the Challenger disaster provides still-crucial lessons about managers who fail to heed the warnings of their own experts. Russell made his tour to make sure NASA officials “heard it from us, and heard the emotional impact that we felt.”

‘America’s finest’

On that day four decades ago, I was standing alongside McAuliffe’s parents and friends. I was a reporter in the Boston Globe’s bureau in Concord, New Hampshire, and I was assigned to follow McAuliffe’s journey from Concord to Cape Canaveral. I visited McAuliffe in her home, flew with her son’s class to Florida and witnessed the disaster.

As the 40th anniversary neared, I revisited McAuliffe’s journey, documented in my clippings as well as thousands of pages of books, reports and previously unpublished material. I tracked down the handful of surviving former officials involved in the launch decision, including the rocket company manager, who reversed himself and signed off on the launch.

What I found are intertwined stories: one of McAuliffe and her fellow crewmates, determined to revive interest in the space program, and another of behind-the-scenes turmoil as rocket engineers all but begged that the launch be scrubbed.

President Ronald Reagan had announced in 1984 that he wanted the first private citizen in space to be “one of America’s finest — a teacher.” McAuliffe was chosen by a government-appointed panel in July 1985 from 11,000 applicants to be the “space teacher.” Invariably portrayed in media as a small-town teacher with a nervous laugh, she was in fact a teacher like few others, a bit of a rebel who was bursting to speak about inequality, woeful pay and the power of politics — if only she was asked.

McAuliffe, 37, taught a history course called The American Women, which included study of astronaut Sally Ride, who in 1983 became the first American woman in space, assigned to the Challenger. Two years later, when McAuliffe learned that Reagan had sought a teacher to be the first civilian in space, she filled out an application seeking to follow in Ride’s path — which, as it happened, would be aboard the same space shuttle.

“As a woman, I have been envious of those men who could participate in the space program and who were encouraged to excel in the areas of math and science,” McAuliffe wrote in her application. “I felt that women had indeed been left outside of one of the most exciting careers available. When Sally Ride and other women began to train as astronauts, I could look among my students and see ahead of them an ever increasing list of opportunities.”

McAuliffe became one of 10 finalists, training with the group and traveling to Cape Canaveral on July 12, 1985, to witness a launch of the Challenger. But the flight was aborted three seconds before liftoff because of a faulty valve. Days later, McAuliffe was unanimously chosen by the government-appointed panel of experts to be the teacher in space, a decision announced at the White House on July 19, 1985, by Vice President George H.W. Bush.

Ten days later, after NASA fixed the valve, the spacecraft launched but was almost immediately in trouble. One of the three engines shut down, leading to concern that the shuttle would have to make an emergency landing. NASA controller Jenny Howard probably saved the mission when she made a split-second decision that faulty sensors caused the shutdown and overrode them, enabling the flight to continue. Twice in two weeks, Challenger had been in danger, but the teacher-in-space show went on.

Only two days later, NASA publicists whisked McAuliffe onto the set of “The Tonight Show,” where she gave host Johnny Carson a kiss and won him over, along with a national audience of millions. The recent problems with Challenger, however, were on her mind, as she said the timing of her flight was “being bumped up a little bit with the problems they’ve had.”

“Are you in any way frightened of something like that?” Carson said, noting that “they had a frightening [incident] and one of the engines went out.”

“I really haven’t thought of it in those terms because I see the shuttle program as a very safe program,” McAuliffe responded. “But I think the disappointment …”

Carson interrupted to recall a joke by another astronaut: “It’s a strange feeling when you realize that every part on this capsule was made by the lowest bidder.”

‘I think it’s important to be involved’

A few days later, McAuliffe was back in Concord and agreed to see me at her gracious three-story house in a neighborhood known as The Hill. Her husband, Steven, who was then in private law practice, listened attentively.

At the time, New Hampshire was a solidly conservative Republican state. McAuliffe was an outspoken activist with political ambition; she had been the head of a local teachers union and, true to her Massachusetts roots, a self-described feminist and Kennedy Democrat.

Although rarely mentioned in national stories, her fight for teacher salaries had made her a local legend when she made the case before a town meeting to raise pay, and she succeeded.

By the time McAuliffe applied to be a teacher in space, New Hampshire teacher salaries averaged only $18,577, better than only Maine and Mississippi, according to NEA statistics, and she made only $24,000 annually after 15 years. When I asked her about the salary fight and the continuing low pay for teachers, McAuliffe looked up from packing a bag labeled “Teacher in Space” and said that, after dozens of interviews, this was the first time she had been asked such a question about education. She hoped that her space mission would give her a platform to fight for teachers.

“My sympathies have always been for working-class people. I grew up in that era — we are real big Kennedy supporters — and I think it’s important to be involved.”

As we discussed McAuliffe’s recent round of rousing public appearances, including on “The Tonight Show,” Steven McAuliffe couldn’t resist hinting about a future in politics: “The Democratic Party could use a good candidate,” he said. “I think she’d be pretty good, don’t you?”

Warning signs

The space shuttle was one of the greatest triumphs in aeronautical design that the world had seen. The airplane-like orbiter carried astronauts and payload such as satellites and could return to Earth for a runway landing. It was launched into space by an external tank with liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen, propelled by two solid rocket boosters that were jettisoned about two minutes into flight and could be reused.

But the solid rocket boosters had a potential weakness. They were constructed in sections at the Morton Thiokol plant in Utah, shipped across the country by rail and reassembled at the Florida launch site. This meant the rocket was fit together at a series of field joints, as they were called, which would have to be sealed with an O-ring, a supersize version of a rubber seal on a kitchen faucet.

The O-rings were only a quarter-inch thick, wrapped around the rocket sections at a circumference of 37 feet. It was well known that the slightest leak in an O-ring could be catastrophic, so a second seal was added for redundancy.

NASA insisted the rockets were so secure that the probability of failure was too small to calculate — they could fly every week for 100 years without incident, the government asserted at one point.

Indeed, when a NASA official briefed McAuliffe and others, he said if a crucial part should fail, a backup assured success, citing the need for such redundancy to prevent “a burn-through in the solid rocket boosters … because we’re very concerned about the first two minutes you’re on the solid rockets. If one of those rockets goes, why, it’s pretty bad,” according to “I Touch the Future,” a 1986 biography of McAuliffe by Robert T. Hohler.

But the warning signs had been piling up.

Seven months before McAuliffe’s selection was announced, Morton Thiokol engineer Roger Boisjoly was alarmed at what he saw during an examination of rockets retrieved after the launch of space shuttle Discovery. That spacecraft had launched after days of what was called a once-in-a-century freeze in which temperatures at the launchpad dropped to 18 degrees. Boisjoly’s postlaunch inspection found damage to O-rings that he determined had been caused by the cold.

Yet when tests confirmed Boisjoly’s thesis, “management insisted that this position be softened,” Boisjoly later said at a Massachusetts Institute of Technology speech.

Boisjoly was so concerned that his warnings were being ignored that on July 31, 1985 — the same day McAuliffe appeared on “The Tonight Show” — he wrote a memo to his superiors ominously titled “SRM O-ring Erosion/Potential Failure Criticality.”

“This letter is written to insure that management is fully aware of the seriousness of the current O-ring erosion problem …” Boisjoly wrote. If there was a repeat of an O-ring problem that occurred on an earlier mission, he feared, “The result would be a catastrophe of the highest order — loss of human life.”

‘I think it’s safe enough’

On the day that the field of teacher-in-space candidates had been narrowed to 10, the shuttle’s commander, Richard Scobee, told his wife, June, that he was concerned about the impression given by NASA about how safe the shuttle program had become.

“They have 10 finalists, and they’re really counting [on] how safe it is to fly the shuttle now,” Scobee said, as June recounted in an interview this month with The Washington Post. “And we know it’s still a test vehicle. It’s not a commercial flight. Should I go to Washington to talk to the 10 finalists?”

June told her husband that he should go, “and if any of them wanted to back out, that’s a good time.”

Scobee delivered his warning to the finalists. None backed out.

After McAuliffe was chosen and traveled to Houston for training, she visited June at her home.

“Do you think it’s really safe?” McAuliffe asked.

“Christa, no one really knows for certain, but if it’s safe enough that I’m encouraging my husband to fly, then I think it’s safe enough,” June responded.

Thinking back on the moment almost 40 years later, June recalled, “She appreciated that. And that’s all I could say. What did I know?”

McAuliffe turned from her round of interviews to an intense training schedule — much compressed compared with that of astronauts — and earned the admiration of skeptical colleagues who at one time saw her as taking away a seat from others who had been waiting years for their turn. Eventually the view was that she had become so popular that she might be the savior of the shuttle program.

As launch day approached, McAuliffe had allowed me to accompany her son’s flight to Florida on Jan. 22, 1986. Scott, 9 years old and accompanied by his third-grade classmates, sat in a window seat as he drew a Martian on a pad. He was looking forward to the launch — and visiting Sea World to see a killer whale.

As the United flight descended through the clouds, Scott looked out the window and saw Kennedy Space Center and the launchpad from which his mother was scheduled to lift off.

“Someone called to him to play a game,” I wrote, “but Scott stayed by the window, transfixed.”

Determined to fly

For several days, launches were planned and scrubbed. McAuliffe’s father, Ed Corrigan, a plainspoken and proud dad, wandered into a Cocoa Beach store that had advertised “Teacher in Space Souvenirs.” The store offered him a 10 percent discount on large buttons with an image of his daughter and, as he told it, he bought dozens and “I’m giving them out like cigars.” He said Christa was “very anxious” and couldn’t wait until liftoff.

The cancellations had made NASA the butt of jokes on national newscasts, particularly the hapless circumstances of Jan. 27, which CBS anchor Dan Rather called a “red faces all around … high-tech low comedy.” That day’s flight was postponed after technicians noticed a screw protruding from a door latch and could not locate a drill to remove it; then, when a drill was found, its battery could not be located. Finally, after hacksawing the screw, high winds canceled the launch. I wrote in my story that day that a NASA official said while there had been only a “minuscule chance” of a problem, “we are dealing with human life here and we don’t take chances.”

The attitude was, ignore the critics, safety first. Or so it seemed.

The plan was to launch the following morning, but the forecast was for an overnight low 0f 18 degrees and freezing temperatures into the morning. It was broadly assumed there would be another cancellation. A year earlier, similar temperatures had been called a once-in-a-century freeze and — unknown to the public — had caused almost catastrophic damage to the O-ring.

But NASA was determined to fly. Questions would later be raised in a congressional investigation and elsewhereabout whether the push to launch was due partly to Reagan’s intention to highlight McAuliffe in his State of the Union speech that evening, but White House officials denied exerting pressure.

Boisjoly, meanwhile, was making one last effort to convince his superiors at Morton Thiokol as well as NASA that they were risking catastrophe. He was joined in a meeting at the company’s Utah facility by Brian Russell, the engineer who had recently been promoted to project manager.

Russell came prepared with data that underscored his concern about whether the O-rings would fail in cold weather. “We were unified as an engineering team going into that meeting on recommending a delay,” Russell said.

That was going to be their message in a teleconference with NASA officials who had gathered at Cape Canaveral and the Marshall Space Flight Center in Alabama. Around 9 p.m. Eastern time — about 12 hours before the scheduled launch, Boisjoly said that no launch should take place if the temperature was below 53 degrees, which seemed to rule out a launch given the forecast. The final word seemed to come from Morton Thiokol’s vice president, Joseph Kilminster.

“I stated, based on the engineering recommendation, I could not recommend launch,” Kilminster, now 91, said in an interview this month.

That could have been the end of the discussion. But NASA officials — who had come up with the teacher-in-space program partly to offset criticism of their costly inability to launch as many shuttle flights as promised — were aghast. While stressing they wouldn’t go against the rocket maker’s recommendation, they made clear they wanted the liftoff to proceed.

“My God, Thiokol, when do you want me to launch, April?!” said Lawrence Mulloy, the NASA solid rocket booster project manager, according to congressional testimony.

The data, NASA officials told Morton Thiokol, was not conclusive. They pressured the company officials to further explain its reasoning. Company officials said they wanted to discuss the matter privately and muted the teleconference.

As Russell recalled it, the company faced great pressure, including the likelihood that NASA was about to solicit competition to build future rockets. “We as a company had a very, very strong desire to please our customer,” Russell said.

As Thiokol paused the teleconference, Kilminster said in the interview, he talked with another company official and became comfortable that liftoff would be safe at the predicted launch-time temperature. The call was resumed, with Mulloy continuing to push for permission to launch.

With urging from a more senior company official as well as space agency officials, Kilminster then reversed himself and supported launching. He said in the interview that while there was pressure from NASA, “I don’t want to say it was the insistence of the NASA people that made me do that.” He also thought that O-rings could perform at a lower temperature than the ambient rate predicted for the following morning.

Looking back, Russell said he wished he had spoken up so that NASA officials on the call would have realized there was strong internal dissent.

“Why didn’t I speak up?” Russell said in the interview. “There had to be on me an intimidation factor that once the decision was made that I would not dare to refute it. That’s my biggest regret. I wish so much that after we had gone back [on the teleconference], I wish I’d have said that there’s a dissenting view here so they would know we’re not unanimous.”

Russell concluded that NASA had turned decision-making on its head. “I’m convinced what happened is that the burden of proof toward safety had been flipped, that we, in our recommendation, could not say, here’s the temperature when it would fail. We couldn’t prove it was going to fail,” Russell said.

Morton Thiokol’s representative at Cape Canaveral, Allan McDonald, could not believe what he was hearing. Like Boisjoly and Russell, he had deep concerns about the effect of the cold on the O-rings. So McDonald took a rare step: He refused to go along.

“I told Mulloy that I would not sign that recommendation,” which he considered “perverse,” McDonald wrote in his memoir, “Truth, Lies and O-rings.” If NASA wanted signed approval, it would have to come from a company official in Utah. The whole exercise, he wrote, was a “Cover Your Ass” effort by NASA.

McDonald made one more effort to cancel liftoff, telling NASA officials: “If anything happens to this launch, I wouldn’t want to be the person that has to stand in front of a Board of Inquiry to explain why we launched outside of the qualification of the solid rocket motor.”

Kilminster signed the document saying that Morton Thiokol supported a liftoff. It wound up being Russell’s task to send the fax that recommended the opposite of what he had wanted. NASA got what it wanted. The launch was a go.

After the meeting, Boisjoly wrote in his log that he and his team had done everything they could to stop a liftoff, writing, “I sincerely hope that launch does not result in a catastrophe.” Later that night, believing that “the chance of having a successful flight was as close to Zero that any calculations could produce,” he vented to his wife, Roberta, according to the account in his unpublished memoir. (Boisjoly, who died in 2012, gave the memoir to Professor Mark Maier, the founder of a leadership program at Chapman University, who provided a copy to The Post.)

“What’s wrong?” Roberta asked her husband.

Responded Boisjoly: “Oh nothing, the idiots have just made a decision to launch Challenger to its destruction and kill the astronauts.”

‘Go Christa!’

That same evening, McAuliffe talked on the phone with her close friend and fellow Concord teacher, Jo Ann Jordan, who was at Cape Canaveral to witness the launch and recalled the conversation in an interview.

“I’ll call you when I get back,” McAuliffe said, and then added with a laugh, “Oh, it sounds like I’m going to New Jersey!”

Early the following morning, McAuliffe put on her blue flight suit, took an elevator up the launchpad, past rows of icicles on the superstructure, and buckled into her seat in the Challenger. She was joined by six crewmates: Scobee; pilot Michael J. Smith; mission specialists Ronald E. McNair, Ellison S. Onizuka and Judith Resnick; and payload specialist Gregory B. Jarvis.

McAuliffe had told a friend what it had been like waiting for liftoff before a flight was canceled: lying on her back, unable to read or watch anything, head in a helmet and her body “strapped down really tightly, with oxygen lines and wires coming out of your suit.” She had packed several mementos, including a T-shirt emblazoned with what became her motto: “I touch the future — I teach.”

Steven McAuliffe, Scott and daughter Caroline, 6, were escorted to a rooftop building to watch the liftoff. Christa’s parents, Ed and Grace Corrigan, arrived with Scott’s third-grade class and other friends to watch from a grandstand. Given my assignment to tell the family’s story, I was escorted to sit near the parents.

The day seemed postcard-perfect crystalline, at least in terms of unlimited visibility and no forecast of precipitation. But the predawn temperature was 22 degrees. As Grace Corrigan later wrote, it was “cold, cold, cold. … We could see icicles hanging from the shuttle. How could they lift off like this?”

Television footage of the icicles on launchpad 39B prompted Rocco Petrone, the president of Rockwell Space Transportation System, a division of the company that built the shuttle, to advise against the launch. As Petrone later testified, he feared the icicles could damage the shuttle, and he told NASA, “Rockwell cannot assure that it is safe to fly.” NASA decided that it had sufficiently dealt with the ice problem, and the warning was dismissed.

For two hours, the launch was delayed. Now it was 11:38 a.m. The temperature had climbed, but the ambient reading was still only 36 degrees, and it was colder at the right field joint of the rocket booster, because of high winds sending super-cold gases down the tank. At company headquarters, engineers were in disbelief that the launch was going ahead.

Indeed, the astronauts had figured such cold would cause a delay, even though they were not apprised of the danger from the O-rings. But NASA had made its decision. McAuliffe’s parents and friends and the students from Scott’s class gathered in front of a large homemade banner that said, “Go Christa!”

‘The vehicle has exploded’

“3, 2, 1!” the children shouted.

A voice from a loudspeaker exulted: “Liftoff! Liftoff of the 25th space shuttle mission, and it has cleared the tower!”

“Look at it, all the colors,” a child said.

Then: “Where is it?”

Seventy-three seconds into flight, massive white plumes billowed from the rockets, painting curlicue contrails. To the untrained naked eye, it was hard to discern whether this was anything other than a routine separation of the shuttle from its rockets.

“It’s beautiful,” said one of McAuliffe’s friends, not realizing.

Aboard Challenger, the last words were spoken by pilot Smith: “Uh-oh.”

Forty-three seconds passed as the confused crowd looked skyward. Finally, a voice came over the loudspeaker: “Flight controllers here are looking very carefully at the situation. Obviously a major malfunction.”

Almost another minute passed.

Mission control: “We have a report from the flight dynamics officer that the vehicle has exploded.”

I looked at Ed and Grace Corrigan, Scott’s classmates, McAuliffe’s friends.

“Contingency procedures are in effect,” said the monotone voice from the speakers.

Again, the loudspeaker voice: “We have a report relayed through the flight dynamics officer that the vehicle has exploded.”

“Oh my God,” said one of the chaperones for Scott’s classmates. “Everyone, get together.”

Jo Ann Jordan, the friend who had talked hours earlier with McAuliffe, exclaimed, “It didn’t explode, it didn’t explode.”

The Corrigans looked shell-shocked, squinting at the white streaks expanding across the sky, obscuring the craft that had carried their daughter. Finally, they inched down the steps of the grandstand, whisked away by a NASA official.

Only later, it was determined the vehicle had not entirely exploded. At least some of the crew members were probably briefly alive, perhaps for as long as two minutes. Evidence later showed that Smith’s personal emergency air pack had been activated for him by another astronaut, and that Smith had turned a switch to regain power. But they were in an uncontrollable piece of the shuttle. Escape was impossible because NASA had decided there was no need to plan for such an emergency. The cabin slammed into the ocean. The remains of the bodies would be recovered from the bottom of the sea.

Reagan canceled his State of the Union speech. He instead delivered a brief address, paraphrasing a famous poem by American aviator John Magee called “High Flight”: “They slipped the surly bonds of Earth to touch the face of God.”

Reagan had no way of knowing it, but McAuliffe had slipped a full copy of the poem into her flight suit before boarding the Challenger.

Back at Morton Thiokol headquarters, Boisjoly and Russell watched the Challenger liftoff from the same conference room where they had opposed the launch only hours earlier. Retreating to Boisjoly’s office, the two embraced and cried. “We just knew inside of us it was us — that it was the booster, it was the joint, it was just what we talked about the night before, we both felt we were profoundly sorrowful,” Russell said in the interview.

‘She died because of NASA’

In those days before the internet and cellphones, and with network television stations broadcasting regular programing, the launch had been carried live by CNN and satellite feeds to classrooms, where millions of schoolchildren saw the events unfold. Within an hour, most Americans had heard the news and seen replays. I wrote an initial story for a rare extra edition, headlined “Globe reporter with family at scene,” accompanied by a massive picture of the explosion. The Post assembled a team of reporters to write a book, “Challengers,” which profiled the astronauts. The disaster became one of the biggest stories in years.

The disaster, after all, had led to the first in-flight deaths of American astronauts. (Three astronauts had died in a launchpad accident in 1967.) Tens of millions of viewers tuned in to watch the televised hearings of an investigative commission. Soon came confirmation of all that the Morton Thiokol engineers had warned about: the years of disregarded red flags that the O-rings were susceptible to the cold, as evidenced by the meeting before the launch at which company engineers were overruled by managers.

Ed Corrigan absorbed it all with growing anger. Like many members of the family, McAuliffe’s father had initially declined to speak against NASA. But after he died in 1990, his widow, Grace, discovered a notebook in which he laid out his feelings. “NASA’s ineptitude,” Ed Corrigan titled one paper, in which he listed the names of those who had opposed the launch, Grace Corrigan later revealed in her memoir, “A Journal for Christa.”

“I have been angry since January 28, 1986, the day Christa was killed,” Ed Corrigan wrote. “My daughter Christa McAuliffe was not an astronaut — she did not die for NASA and the space program — she died because of NASA and its egos, marginal decision, ignorance and irresponsibility. NASA betrayed seven people who deserved to live.”

NASA officials said in congressional hearings that they made the decision based on information supplied to them at the time, including the faxed recommendation for launch from the Morton Thiokol official who had reversed himself.

While much became known in the weeks following the explosion, more information has emerged in the ensuing four decades. McDonald published his memoir in 2009 and died in 2021. Boisjoly, who often spoke about his anger about his unheeded warnings and documented his actions in his unpublished memoir, which was cited in a 2024 book, “Challenger,” by Adam Higginbotham. Some of those involved in the launch decision gave interviews for a 2020 Netflix documentary, “Challenger: The Final Flight.” Among them was Mulloy, the project manager at Marshall Space Flight Center who pushed Morton Thiokol to reverse his recommendation.

“I feel I was to blame,” said Mulloy, who died at 86 years old in 2020. “But I felt no guilt.”

Kilminster, the Thiokol vice president who reversed himself to recommend a launch, spent the following 40 years seeing himself cast as a villain. He said in his interview with The Post that he is “haunted by the fact that I was involved in a solid rocket and motor launch decision resulting in the deaths of seven extremely capable, dedicated and admirable individuals.”

But Kilminster also said he has been wrongly singled out. Kilminster said that he had been unaware at the time that the shuttle’s tanks had been venting liquid oxygen longer than he considered usual, which he said meant super-cold oxygen flowed downward and caused the O-rings to be much colder than the ambient temperatures.

“The temperature on the O-rings was a lot colder than anyone wanted to admit,” Kilminster said. Had he known that temperature at the field joint was colder than he considered acceptable, he said there is “no question” he would have reversed himself again and opposed the launch.

A number of engineers who worked under Kilminster have said, however, that even the ambient temperature of 36 degrees at liftoff was more than cold enough to have followed their recommendation against a launch. While Russell said he did not doubt that it was much colder at the O-ring, “the ambient temperature was cold enough to make me concerned and wanting a delay.”

A presidential commission determined that cold temperatures caused the O-ring failure, as well as flawed decisions and internal conflicts leading up to the launch. It was not within the commission’s mandate to judge whether NASA was at fault for putting McAuliffe on the flight. However, Alton Keel, who was the executive director of the commission, said in an interview that the lesson was clear to him then and now.

“They let the PR get in the way of good judgment,” Keel said. “A tragic example of that was Christa McAuliffe. She should not have been put on that flight. I’m sorry. But those flights were experiments. There’s too much risk involved.”

The rocket booster was redesigned by Morton Thiokol and never again failed. But in 2003, the space shuttle Columbia broke up during its return to Earth because its wing had been hit by a loose piece of insulating foam. An investigation found that, as in the Challenger disaster, NASA mismanagement was partly to blame. The last shuttle flew in 2011.

Wayne Hale, a former NASA flight director who worked on many shuttle launches, said in an interview that the culture changed after Challenger in which “safety was much more important than schedule,” encouraging dissent with the establishment of an anonymous reporting system and other measures. Still, he warned that “no matter how well things are prepared, there’s still a huge element of risk involved.”

‘This is still difficult for me’

The disaster profoundly influenced my outlook as a journalist, a career that soon took me to Washington, where I have spent much of the past 40 years covering the White House and those who seek to occupy it. In the wake of the Challenger explosion, I vowed that I would remember how NASA officials assured the public about the shuttle’s safety, and I sought to probe beyond official statements. And I would apply what I called the O-ring lesson: Make every story as airtight as possible. The O-ring failure proved the aphorism that nothing is stronger than its weakest link.

Steven McAuliffe has sought to keep the focus on his wife’s work for education. A little more than five months after the explosion, he delivered a speech to the National Education Association, in which he urged members to remember her legacy by working “until we have a system that honors teachers and rewards teachers as they deserve.”

Forty years later, that mission is still a work in progress. New Hampshire today ranks 38th in starting teacher salaries, at an average of $42,588, according to the National Education Association.

In 1992, seven years after George H.W. Bush had announced Christa McAuliffe’s selection at the White House, Bush was president and nominated Steven McAuliffe to be a judge on the U.S. District Court in New Hampshire — a seat that McAuliffe still holds under part-time senior status. The pick transcended the fact that McAuliffe was an outspoken Democrat and Bush was a Republican seeking reelection.

Steven McAuliffe, who remarried and still lives in New Hampshire’s capital city, spoke in September 2024 at the unveiling of a statue of Christa on the State House lawn. He focused on Christa’s support for teachers, which he has said is democracy’s lifeline and was “far more” important to her than spaceflight.

“This is still difficult for me,” McAuliffe, who did not respond to an interview request, told the crowd of schoolchildren, friends and politicians. “Which I guess I’m kind of proud of.”

June Scobee Rodgers, the widow of the Challenger commander, said that soon after the disaster, she talked to the other family members about a way to ensure that the mission’s message is not forgotten.

“I know NASA will continue spaceflight — they have to,” she said. “But who will continue Christa’s lessons? I talked to the other families and I said, these lessons aren’t just a textbook, they are a real-world application of adventures in space.” That led her to spearhead the development of Challenger Center, which has 33 locations. Students who visit the centers take part in a simulated space mission that faces a crisis, either in a mock spacecraft or mission control, as a way to stimulate interest in math, science and aerospace.

“I hope and pray to this day that’s what Christa would want,” Scobee Rodgers said.

Although Scobee Rodgers knew much about the disaster, she said it wasn’t until recent years that she fully realized how aggressively the rocket company’s engineers had tried to cancel the launch, understood how NASA was motivated by its drive for boosting its support, and saw enhanced video showing an early leak at the O-ring, among other factors.

“I finally understood,” she said.

Last week, Scobee Rodgers stood silently with a bouquet at Arlington National Cemetery, where she and other family members of fallen astronauts attended NASA’s “Day of Remembrance.”

For Russell, the Challenger mission has never really ended. Last year, he visited NASA centers across the country to deliver a presentation about the lessons that are as relevant as ever: Leaders need to listen to warnings from those who work directly on the spacecraft.

“The whole goal of it was to make the team better and learn from our experience,” he said. “I would tell them flat out: I really wish and hope with all my being that you will do better than we did.”

Aaron Schaffer contributed to this report.

The post 40 years later, a new look at lessons from the Challenger disaster appeared first on Washington Post.