We were the children who queued outside bookstores and cinemas at midnight. We got Harry Potter tattoos, threw Harry Potter themed weddings and named our children after characters from the novels — baby names like Hermione, Luna and Draco.

We interpreted our politics through the lens of the wizarding world, comparing those we disagreed with to the books’ main villain, Lord Voldemort, and carrying signs with slogans like “Dumbledore’s Army” and “Hermione wouldn’t stand for this!” at Women’s Marches. And some of us even took deeper moral cues from the books, reading them like a new Bible, treating the works as sacred texts with religious teachings to convey. Some fans experienced J.K. Rowling’s controversial comments on transgender rights as a betrayal precisely because they had seen her as one of our generation’s most influential moral guides.

It’s been almost 20 years since the final Harry Potter book was released. The wizarding world is still generating interest — book sales remain strong, and the 2023 video game Hogwarts Legacy, topped 40 million sales. HBO is working on a TV adaptation of the books, set to be released next year.

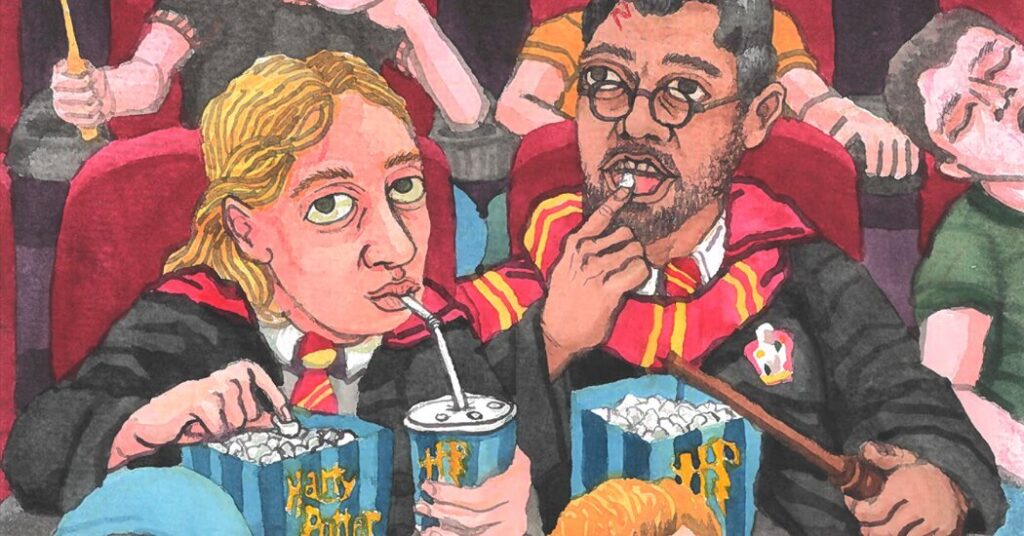

But the relevance of the franchise is waning. “We’ve seen our audience age up,” conceded a Warner Bros. executive of the recent spinoff films. When the first of these, “Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them,” premiered in 2016, just 18 percent of cinema goers were actual children. Most were older than 25, a trend that did not go unnoticed by Zoomers who like to poke fun at my generation for clinging onto our childhood passion. “You’re not a Slytherin, Katherine. You’re 36,” quips the Gen Z comedian Brittany Broski, addressing an imagined “Harry Potter adult” in a TikTok with millions of likes.

You don’t see this with fiction like “The Lord of the Rings” or “The Chronicles of Narnia.” Sales of those books may rise and fall in response to new film or TV adaptations, but those franchises aren’t bound to a particular generation in the way that Harry Potter is bound to the millennials. Perhaps that is partly a consequence of the fact that, as children, millennials experienced the release of both the Harry Potter books and the Warner Bros. films as a series of multimedia events that were skillfully hyped.

But there are also politics at play. Ms. Rowling foregrounds ideology in her books, and that means that her novels feel dated in a way that others do not. First conceived of over 30 years ago, the Harry Potter books are very much a product of 1990s liberalism: a moment when World War II still occupied a central space in the cultural imagination, and when it was still possible to believe that the best bits of the old political order could be retained alongside a gentle incorporation of the new.

That’s why millennials like Harry Potter a whole lot more than younger generations do. The story captures a worldview that is no longer attractive to young people jaded by the experiences of economic decline, political polarization and spiraling identity politics. They have fallen out of love with Harry Potter because they have fallen out of love with the worldview the series represents. Which is to say that young people have fallen out of love with liberalism.

The first Harry Potter book was completed by Ms. Rowling in 1995 when she was a single mother living with her young daughter in Edinburgh, having fled an abusive marriage. She and her baby were, she later said, “as poor as it is possible to be in modern Britain, without being homeless,” and this experience left her with a lifelong commitment to the welfare state. Although Ms. Rowling is now a billionaire, she lost that status in 2012 because she gave so much of her money away, primarily to children’s charities, but also to political causes, including 1 million pounds to Britain’s left-wing Labour Party in 2008. Despite the furor over her views on gender, Ms. Rowling continues to describe herself as a “left-leaning liberal” — in fact, she insists that these views are entirely in keeping with the rest of her politics, and her books.

In the wizarding world, good people are easy to spot because they are committed to liberal virtues like tolerance, free speech and nonviolence. The small number of ethnic minority characters are absorbed within a cheerfully colorblind society. But a grand metaphor for racism — a preoccupation with being a “pure-blood” wizard whose ancestors were exclusively magical, rather than “muggle” — gives the story its moral momentum, as good wizards do battle against bad wizards — most importantly, the would-be tyrant Voldemort — who wish to institute a violent, pure-blood-supremacist regime.

World War II looms large here. Although it isn’t made explicit in the books, Ms. Rowling hints at a connection between the evil of her imagined world and the evil of Nazi Germany by gesturing to a previous evil tyrant by the name of Gellert Grindelwald, defeated in 1945, whose headquarters were in Austria. When Voldemort seizes power in the final installment of the series, he introduces a “Muggle-Born Registration Commission” intended to recall the Nuremberg Race Laws. The most recent iteration of the wizarding world film franchise makes the Nazi link explicit by setting the drama in 1930s Berlin and adding some anachronistic 21st-century political vocabulary. “The world as we know it is coming undone,” one character tells us. “Gellert’s pulling it apart with hate, bigotry.”

Harry Potter both reflected and reinforced the politics of readers who came of age during the postwar liberal era. One 2014 study, cited by Hillary Clinton during a speech on the importance of libraries, suggested that reading Harry Potter increased sympathy toward immigrants, gay people and refugees. In another piece of research published in 2013, Anthony Gierzynski, a professor of political science at the University of Vermont, with the artist Kathryn Eddy, tested the hypothesis that millennials who read Harry Potter ended up mirroring the political ideals of the books more than those who didn’t:

We found that Harry Potter fans tend to be more accepting of those who are different, to be more politically tolerant, to be more supportive of equality, to be less authoritarian, to be more opposed to the use of violence and torture, to be less cynical, and to evince a higher level of political efficacy.

Millennial politics, at least the left-wing variety, rhymed so well with the morals of the wizarding world that in the wake of President Trump’s first inauguration, liberal media was replete with headlines like “How Harry Potter helps make sense of Trump’s world” and “Who Said It: Steve Bannon Or Lord Voldemort?” In 2017, a group of graduate students at Harvard started an anti-Trump group that was likened to “Dumbledore’s Army”— a coalition of students who, in the novels, unite to resist Voldemort. Ms. Rowling herself has weighed in on the Trump comparisons — “Voldemort” she wrote in 2015, “was nowhere near as bad.”

But though Mr. Trump is back in office, you are far less likely to find a Zoomer making this kind of comparison. The liberal values listed by Dr. Gierzynski — political tolerance, opposition to authoritarianism and violence, and faith in the democratic system — are increasingly lacking among young Americans who evince less support for free speech, more cynicism about democracy and more tolerance of political violence.

Zoomers were forged in a different world. Theirs is a generation that came of age after the global financial crisis of 2008 and has since witnessed long periods of stagnant wages and declining state stability, not only in America but also across much of the Western world. They are a generation that has barely known an optimistic period of politics (a Zoomer might have been only 12 at the end of President Barack Obama’s second term) — a generation more likely than their predecessors to view their lives as controlled by external forces, rather than by their own choices and will.

That may help explain why the optimism within the Harry Potter universe no longer lands in today’s climate. The protagonists of Harry Potter are not especially remarkable people — they’re talented in some ways, and often courageous, but Ms. Rowling very much emphasizes their ordinariness. She asks us to believe that ordinary people — children, at that — are capable of defeating the forces of evil. “It’s a book about winners,” as one younger friend pointed out to me, and Zoomers really don’t see themselves that way.

Young people on both the right and left are also less wedded to political institutions. Those of us born in the 20th century had grown used to the idea that the right stands for tradition and the left for reform. In the liberal era, everyone was expected to hew quite closely to the status quo.

But what we see now is that both factions stand for revolution. The conservative writer Rod Dreher recently asked a young man in Washington to outline the demands of his generation’s right-wing radicals. “They don’t have any,” he replied, “they just want to tear everything down.”

The Zoomer left is no less radical. In Harry Potter, the good guys do not deliberately kill, but instead stun or disarm their opponents. Here Ms. Rowling endorses a liberal commitment to nonviolence that appears to be falling out of favor, particularly on the left. In a recent YouGov poll, the respondents most likely to endorse the statement “political violence can sometimes be justified” skewed young and left wing. We saw a glimpse of this change in norms after the assassination of Charlie Kirk, when some young leftists responded with indifference bordering on glee.

Nor does the moral heartbeat of the books — that World War II-inflected fight against bigotry — resonate in the same way today. It’s not just that antisemitism is resurgent among both anti-Zionist activists on the left and the so-called “groypers” on the right (although it is). It’s also that young people are less likely to have known someone who lived through the war as an adult.

Surveys indicate that knowledge of the basic facts of the Holocaust is declining among younger generations. Perhaps that’s why the allusions to World War II are so much more explicit in the more recent installments of the Harry Potter franchise — a few decades ago, consumers could be relied upon to understand subtle references to the Holocaust, but that’s no longer a given.

On the right — and particularly among young men and boys — there has been a souring in attitudes toward liberal ideas of all kinds. Even non-groypers resent the way that the words “fascist” and “Nazi” have been deployed for years against the most milquetoast figures, and exposure to institutional progressivism in schools and universities has provoked an almighty backlash. For the online right, the fact that Ms. Rowling is now so disliked by her erstwhile political allies is often interpreted as just deserts. The prominent far-right wing YouTuber Paul Joseph Watson, for instance, responded to the author’s travails with delight, saying that she had been “canceled by the very same woke outrage mob that she helped create.”

Even before Ms. Rowling weighed in on the debate on trans rights, part of the young left had already condemned her as problematic across multiple fronts: for alleged tokenisation of ethnic minority characters, for her portrayal of slavery and for tropes that some read as antisemitic. From the perspective of many of her critics on the left, Ms. Rowling’s statements on gender sealed the deal on their disavowal of her.

More generous-spirited readers do realize that the politics of Harry Potter are fundamentally progressive. One recent Vox article conceded, alongside many criticisms of Ms. Rowling’s politics, that “the main moral message of the books is this: We shouldn’t live in a supremacist society.” One 26-year-old who identifies firmly as a progressive told me that her peers see J.K. Rowling’s position on trans rights as “disappointing” precisely because they recognize that she is otherwise on their side.

The first Harry Potter book was published in 1997, the same year that Tony Blair’s Labour Party adopted the D:Ream song “Things Can Only Get Better” as the anthem of their (ultimately successful) campaign. I often wonder if I feel nostalgic for the 1990s only because that was the decade of my childhood. But it does seem to me, admittedly across a gulf of time, that a lot of people really did feel then that things could only get better. For all of their occasional darkness, the Harry Potter books reflect the hopeful vision distinctive to the time and place of their creation. And the Harry Potter generation imbibed exactly the message that they were supposed to imbibe: that liberalism will always triumph over the forces of evil. Young people just don’t think like that anymore.

Honestly, I don’t blame them. I’m a graying millennial who loved Harry Potter with all her heart, and I am as alarmed as anyone by the increasing illiberalism of young Americans. But I also recognize that they are reacting against a politics that now seems rather naïve.

Liberalism is not the human default. It is a style of doing politics that can be sustained only in a society that is peaceful, affluent and high-trust all at once — a rare combination in our species’ history. Under such conditions, we might well see a widespread tolerance of free speech, a rejection of political violence and a popular faith in democratic processes. But when a society becomes more fractured and more threatened, those ideals may be quickly abandoned, and the aging elites who oversaw the process of decline will not be looked on kindly. Even — or especially — if their mistakes were borne of complacency.

One of the magical creations that Ms. Rowling offers to us — borrowed from “Narcissus,” “Snow White,” “Alice in Wonderland” and other tales — is the Mirror of Erised, an object that allows us to see the “deepest, most desperate desire of our hearts.” When the orphaned Harry first looks in the mirror, he sees himself surrounded by the family that he has never known. Others see themselves rich and successful. Dumbledore warns against the dangers of the mirror: “Men have wasted away before it, entranced by what they have seen, or been driven mad, not knowing if what it shows is real or even possible.”

I now wonder if the Harry Potter books themselves functioned as something like a Mirror of Erised for my generation. They reflected an image of the world that we so wanted to be real: a world that was ancient and magical, where even children had the ability to identify and vanquish evil. It was beautiful in its moral simplicity. It was also too good to be true.

Louise Perry is a journalist based in Britain. She is the author of “The Case Against the Sexual Revolution” and the host of the podcast “Maiden Mother Matriarch.”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.