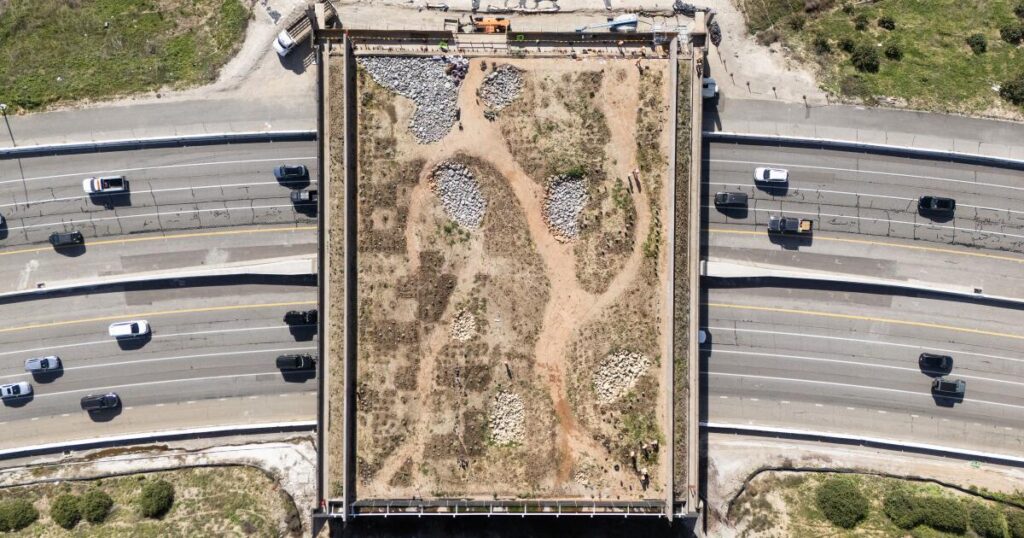

To the 300,000 drivers who stream through Agoura Hills on the 101 Freeway every day, the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing looks relatively unchanged from last summer, except for some leggy native shrubs growing along the outer walls.

While activity seems to have halted on what is touted to be the world’s largest wildlife crossing, there’s been lots of slow, expensive work at the site that’s hard to spot from the freeway, said Robert Rock, chief executive of Chicago-based Rock Design Associates and the landscape architect overseeing the project. This includes:

- Moving power lines, water lines and other utilities underground — at a cost of nearly $20 million — along the south side of the crossing.

- Drilling at least 140 deep holes along 175 feet of Agoura Road and filling them with concrete to create the foundation for the tunnel over the frontage road. The tunnel will support roughly 3 million cubic feet of soil connecting the south side of the crossing to the Santa Monica Mountains, roughly enough soil to fill half of SoFi Stadium, Rock said.

- Reworking some of the project’s nonwildlife-centered designs to reduce ballooning construction costs. For instance, an underground tunnel that would have permitted utility companies to drive in and check on their equipment has been reduced to a large conduit just big enough for wires and cables to be easily pulled through.

Rock and Beth Pratt, California regional executive director of the National Wildlife Federation and leader of the Save LA Cougars campaign, led a tour on top of the crossing during a sunny day last week to discuss the status of the long-awaited project, whose completion date was originally scheduled for the end of 2025.

Record rains in 2022 and 2023 created significant delays, pushing the expected completion of the wildlife crossing to the end of this year.

“We want rainfall. We want water because that’s part of making these landscapes healthy and vibrant,” Rock said, “but when you have 14½ inches of rain in 24 hours and an open excavation for the foundation of a massive structure that fills up like a giant bathtub and you’ve got to vacuum all that sludge out of there three separate times and re-compact the soil … you’re going to have delays even if the contractors are moving at lightning speed.”

Rock said the new completion date in November or early December is “aggressive but doable” since the utility moving is now completed, and he expects work to move more rapidly once the the tunnel foundations are completed. The concrete tunnel will be built on-site and then covered with soil this summer. Most of the earth is coming from a small hill on the north side of the crossing that was created when the freeway was built in the 1950s.

The second and final phase of the project — attaching the shoulders that will permit animals to use the crossing — started last summer and is progressing on schedule, Rock said, but it’s also painstaking, expensive and largely invisible work moving overhead power lines underground and drilling thick holes about 70 feet deep. Once a hole is dug, a tall crane slowly slides in a rebar cage that resembles a wire mesh dinosaur spine so the hole can be filled with concrete.

The work is hidden from most freeway passersby and those driving below since Agoura Road is closed during weekday working hours.

This project has more complexities than others around the country, Rock and Pratt said. Other crossings are typically located in more rural areas and chosen based on ease of construction. The location of this crossing was locked in — a slim passage of wilderness in a largely urban area between the Santa Monica Mountains and Simi Hills — so it faced challenges other crossings usually don’t such as moving utilities, skirting heritage oaks no one wants to remove or working around huge numbers of cars. “If we could have closed Agoura Road and the 101, I could have built it in a year,” Pratt said, laughing.

Rising construction costs have been another complication. The expected cost of the entire project, $92.6 million, held until last spring when the bids for the second phase “came back through-the-roof high,” Pratt said.

The contractor C.A. Rasmussen’s bids for Stage 1 of the project came in 8% below Caltran’s estimate, but the bids for Stage 2 pushed the costs about $21 million higher than expected, increasing the total projected cost to about $114 million.

About $77 million of the construction costs will be paid by state money, including a recent infusion of $18 million to help cover the shortfall, “primarily from conservation funds such as voter-approved bond measures or mitigation dollars,” Pratt wrote in an email. Private donors have provided the remaining $37 million, about 32% of the project’s overall construction costs. About $29.4 million of those private donations came from Wallis Annenberg, the crossing’s namesake, who helped kick-start the campaign with $1 million in 2016, after a “60 Minutes” report about the existential peril facing Los Angeles County’s freeway-locked cougars, Pratt said in an interview Friday.

Annenberg, who died last year, contributed $35.5 million for the project, including the $29.4 million specifically for the crossing construction as well as funds to cover design costs, ongoing wildlife research in the region and the project’s native plant nursery.

Construction costs have gone up everywhere over the past year, in large part because of uncertainty about what even the most basic materials such as concrete will cost, said Rock.

“If you’re putting together a bid for a project and you don’t know what the cost of something is going to be a month from now, let alone six months to a year from now, you’re going to roll that speculation into the cost of your pricing, even when you’re talking about something that should be a fairly stable [cost],” Rock said.

Some of that uncertainty is based on the wildfires that decimated large swaths of Altadena, Pacific Palisades and Malibu last January, he said, because the heavy equipment needed for the project was suddenly in huge demand to clear burned properties. And tariffs on Canada and Mexico, two of the country’s largest suppliers of cement, an essential ingredient of concrete, further increased prices on one of the project’s key materials, even among domestic providers, he said.

The project has enough money now to complete construction, Pratt said, but Save LA Cougars is still fundraising, trying to raise another $6 million to cover other non-construction costs including $2 million for the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy, which owns the land, to maintain the crossing habitat (such as removing invasive nonnative black mustard plants that have taken over the north side of the crossing in the Simi Hills).

In an email outlining the costs, Pratt said the money will also provide $1.5 million to the National Park Service to continue the wildlife research that led to the creation of the crossing, when scientists discovered that the freeways crisscrossing the region were making it impossible for cougars and other wildlife to find suitable mates. It will also be used to fund education programs, maintain the crossing’s nursery and train volunteer docents leading popular tours around (but not on) the crossing.

“As this is being regarded as a global model for urban wildlife conservation and connectivity, we have to ensure the research and educational efforts continue for the long-term,” she wrote.

The project’s rising costs have created anxiety for her. “When I saw the Stage 2 bid, I almost had a heart attack,” Pratt said last week. But during the tour, she was too distracted by the progress on the crossing to dwell on the stress. In midsentence, she’d suddenly break off to excitedly note a young kestrel flying near the crossing or a honeybee foraging among some early flowers.

These days the top of the crossing is busy with workers planting hundreds of native plants grown from seed at the project’s nursery nearby. There are plugs of grasses and gallon pots of white sage, purple sage, California buckwheat, long-stem buckwheat, deerweed, narrow leaf milkweed and coyote bush. The top is divided into 10-by-10 grids bristling with small colorful flags designating where the plants should be placed.

Habitat restoration is a huge part of this project, especially since a wide swath of the area was destroyed by the Woolsey fire in 2018, allowing invasive mustard plants to get a firm hold especially on the north side of the crossing. The native plants selected for the crossing all grow nearby, but Rock said the builders also want to make sure they plant the sages, buckwheats and grasses in the same groupings you would find in nature.

Pratt’s stuffed cougar, representing the late P-22whose bachelor life trapped in Griffith Park helped inspire the project, sat placidly amid workers moving native plants onto the site. She brings him to tours she said, to help remind everyone what the project is ultimately about — saving wildlife.

Wild animals seem curious about the status of the project. A small herd of mule deer have been spotted nosing around the site of the tunnel construction on Agoura Road and in October, a young female cougar named P-129 was briefly captured and collared in a glen of oaks near the south side of the crossing, said Pratt.

Animals can’t easily get on the crossing now unless they can fly. The top is about 30 feet above the freeway, and the north edge is roughly 50 feet from the hills where it will eventually be connected.

Those sides will have to be carefully filled in, a little on one side, then a little on the other to keep the structure from rocking and falling over, Rock said. Once the soil is packed into place, workers will have to add more native plants to cover those shoulders, about 13 acres in all.

Pratt has immersed herself in wildlife for decades. She recently completed writing a book, “Yosemite Wildlife: The Wonder of Animal Life in California’s Sierra Nevada,” about the wildlife near her home in Northern California, and she’s excited about the prospect of insects, birds and other critters investigating the plants now covering the crossing’s top.

The recent wildlife sightings have caused her to rethink which wild animal will be the first to cross. Originally, she said, she was betting on a coyote, but now she’s putting her money on mule deer.

Rock was quieter. He’s happy about the progress, he said, “but I’m more riddled with anxiety than pride right now because there’s still so much work to be done to make sure we’re giving everything the best possible chance for success.”

Navigating the obstacles while upholding the project’s goals such as creating a self-sustaining native habitat over one of the country’s busiest freeways is critical, he said, because the outcome will influence decisions about future crossings.

The project has had some serious problems, he said, “the kind where people go back into their shells because things are difficult, and they’ve hit a roadblock. But I’m hoping that what we’re doing can become a catalyst for people to take a chance and continue to push down the path even though things are challenging.”

The post Despite appearances, the Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing is on track for fall completion appeared first on Los Angeles Times.