Without Trumpism, Democrats and anti–Donald Trump conservatives tell themselves, America can once again be the nation it always was. This political moment, many feel certain, is an aberration, an unfortunate detour from who we are and what we stand for. Surely, they hope, if the MAGA Republicans can just be unseated in this fall’s midterm elections, then once Trump leaves office, this country can get back on track.

But the political space we inhabit has deep roots. It did not erupt out of nowhere in 2016. The racialized rage and contempt for the rule of law that so thoroughly mark the present are the products of a longer political project set in motion during the 1980s, when the Reagan Revolution—itself anchored in white resentment—recast racial violence as necessary and defensible, restoring to it a legitimacy that had not been seen since the Jim Crow era and the Gilded Age.

[Clint Smith: Those who try to erase history will fail]

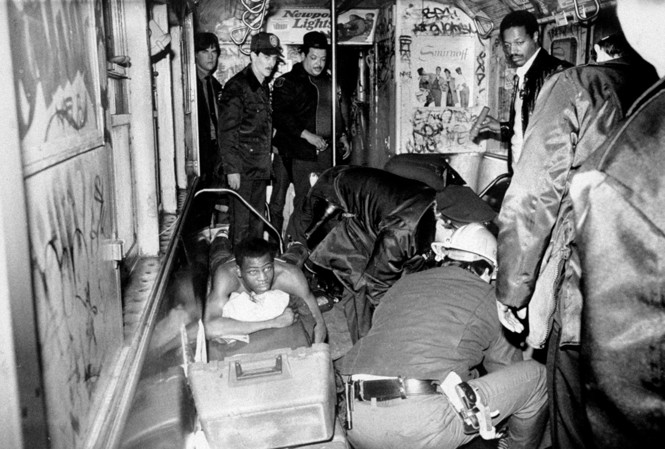

One particularly notorious event, which took place four decades ago on a New York City subway car just three days before Christmas, both reflected and fueled this dramatic political shift. On December 22, 1984, a downtown-bound 2 train rattled out of the 14th Street station, its walls layered in graffiti, its riders reading newspapers or staring silently in the exhausted intimacy of a city still struggling to rebound from a major fiscal crisis in the 1970s—and finding this new decade even more challenging.

On the subway car that day were four Black teenagers who lived in the same housing project in the heart of the South Bronx—Darrell Cabey, James Ramseur, Barry Allen, and Troy Canty. This neighborhood had been especially ravaged in recent years: recreational opportunities ended, public libraries closed, streets left grim by an illegal economy of drugs and sex that had become one of the few remaining ways to make money. With little else to do on what was an unseasonably balmy afternoon, this group of friends decided to head into Manhattan. Their plan for the day was modest and desperate at once—to stop at a video arcade, jimmy open a few coin receptacles, and come away with at least a few stolen dollars in their pockets.

Seated in the same car, directly across from two of the teenagers, was a white loner named Bernie Goetz. A 37-year-old single, self-employed electronics nerd living in Greenwich Village, Goetz was also trying to simply live his life in a city coming apart at the seams. He still had a decent income and a roof over his head, but Goetz’s own material security did not temper the growing resentment he felt every time he stepped outside his apartment and onto city streets. Disconcerting numbers of unhoused people were in Union Square Park, and visibly ill men—gaunt, with lesions and ragged coughs—streamed each day into the emergency room at the nearby St. Vincent’s Hospital. Meanwhile, trash littered the sidewalks and piled up on stoops, and the illicit economy seemed to occupy every corner.

Goetz understood this disorder not as the product of scant civic resources or state retreat but rather as the result of liberal misrule—do-gooder bureaucrats, failed social programs, and a city that had coddled the undeserving and the criminal. He had long since concluded that ordinary men like him would just have to look out for themselves.

When he took his seat on the 2 train that Saturday, Goetz had just spent a frustrating morning working on a piece of electrical equipment and had decided to head downtown for a bit. As he now regularly did, he was carrying a loaded .38-caliber Smith & Wesson hidden in a quick-draw holster inside his waistband.

Canty took in the white guy who had boarded at Union Square, paused the fooling-around that he had been doing with his friends—slapping at the plastic straps that hung from the ceiling of the train car, joking loudly—and greeted the man. Encouraged when he got a terse “Fine” after a “How are you?” Canty asked if the man had $5. He didn’t mind panhandling. That had become a way of life for the city’s poorest residents, young and old alike.

Allen was even more encouraged when this man stood slowly, turning as if he might be getting his wallet. But then Goetz swung back around, assumed a combat stance, and began firing.

Within seconds, Goetz shot Canty in the chest and Allen, who had been standing nearby, in the back as he tried to flee. Goetz next aimed his weapon at Ramseur and then Cabey, who sat farther down the car. He hit Ramseur, who was also trying to run. The bullet pierced Ramseur’s arm and entered his chest through his side. But Goetz’s fourth bullet missed Cabey, and the shooter was, as he later made clear, determined to take every one of the kids out.

As Cabey cowered in his seat, Goetz walked over to him and said, “You seem to be all right. Here’s another,” before shooting at him again from point-blank range.

Goetz didn’t kill these teenagers, but not because he hadn’t tried. He later said, “If I had more bullets, I would have shot ’em all again and again. My problem was I ran out of bullets.”

Yet this man, who then disappeared into the tunnels of the NYC subway system and remained on the lam for nine days, was not reviled as a vicious and violent criminal by a stunning number of New Yorkers, particularly white ones. Goetz became an overnight celebrity, heralded as a real-life “Death Wish Vigilante,” a reference to the blockbuster movies of this era, in which Charles Bronson plays a regular white guy who chooses to meet urban threats with lethal force. Here was a man who had had enough, who had done what others wished they could.

Goetz’s victims were, in turn, villainized and bombarded with hate mail. No matter that these young people were all only 18 or 19, and also unarmed and slight, the tallest of them only 5 feet 6 inches. No matter that Goetz had severed Cabey’s spinal cord and permanently paralyzed him from the waist down. No matter that Ramseur was found dead, likely from suicide, on an anniversary of this horrific event, and that Allen would descend into drug addiction.

They were deemed thugs and animals, and were said to symbolize all that was wrong with America’s cities as well as with the liberals who had enabled the city’s poor, lazy, and criminal elements. They were proof that hard-working Americans were under siege. These teens had gotten exactly what they deserved.

But the public’s reaction to the subway shooting was neither obvious nor inevitable; it was actively cultivated. Doing much of the work to normalize hatred and violence after the event were conservative, misinformation-driven media that were themselves aggressive and ascendant. The Goetz case was a long-awaited opportunity, particularly for the conservative Australian media mogul Rupert Murdoch, who dreamed of making his paper the New York Post the dominant tabloid in NYC and then taking over the entire U.S. news-media market.

From the moment that Goetz pulled the trigger on Cabey, Ramseur, Allen, and Canty, columnists from both the New York Post and the other major New York tabloid trying to hold its own, the Daily News, framed the case as a referendum on self-defense rather than an act of attempted murder. Even though the teens were the ones in ICUs and Goetz had been carrying an illegal weapon on the train that day, they were the “predator” and he was the “prey.”

During the 1980s, both tabloids pandered to the racial resentments and fears of white New Yorkers when covering all of the city’s ills. The New York Post seemed to practically invite readers to cheer for acts of white rage—in the Goetz case and the brutal white-mob killings of Black New Yorkers in Howard Beach and later in Bensonhurst—as well as to steadfastly ignore the civic wreckage that had paved the way for such acts of lawlessness in the first place.

Facts had begun to matter less and less. For example, even though it was fiction, a story that the teenagers Goetz shot were wielding sharpened screwdrivers soon became gospel in tabloid and mainstream press alike. This very much mattered to how the public felt about the case.

But what mattered more was a political shift that was taking place, one that had made it possible for the right-leaning media to profit so handsomely off the resentment and rage of ordinary people.

In 1980, Ronald Reagan took the White House. He insisted that government was bloated and inefficient, that liberal social programs bred only dependency and crime, and that law-abiding citizens, implicitly white, had been abandoned in favor of a lazy “underclass,” often marked explicitly as Black. The Reagan administration counted on Murdoch’s newspapers to hammer away at these messages on its behalf.

According to Reagan Republicans, America’s problems could be solved by cutting federal spending, slashing taxes, and gutting regulations on business. If the rich thrived, their argument went, the benefits would trickle downward to the nation as a whole.

The desire to do all of these things was not new—it had long animated the ambitions of the country’s wealthiest Americans. Ever since the New Deal had constructed a meaningful social safety net in response to the devastation of the Great Depression, the rich had sought to weaken labor, shrink the public sector, delegitimize redistributive social policies, deregulate finance and industry, and drive taxes lower. They had long insisted that private control of public life simply made sense.

Yet it was politically risky for any administration to openly slash the tax base that funded public schools, affordable housing, city services, and public-health systems. As jobs disappear, wages fall, housing and health care grow scarce, and education becomes an engine of debt, people might not only be left poorer; they also might demand accountability and redress.

Reagan Republicans fully understood the political risks of dismantling more than 50 years of public policy, yet—more effectively than any of their predecessors—they succeeded in manufacturing the popular consent needed to do precisely that. The key to this achievement was a simple but devastating insight: The most effective way to discredit liberal social policy was to starve it of resources and then point to its inevitable failure. As the Reagan aide James Cicconi explained in an internal memo, the era of “decreasing governmental resources” would make the “liberal approach” to governance “impossible to sustain financially.” This would force the adoption of “alternatives.”

With each passing year of the 1980s, this engineered collapse was recast as proof that the nation’s problems flowed from liberal social, political, and racial policies, and from the supposed moral failures of people who, it was claimed, simply did not want to work. Inequality was framed as meritocracy.

As the Reagan Revolution matured, taxes were slashed and regulations rolled back; in turn, the social programs and city services upon which ordinary Americans depended were devastated. And as the rich grew richer and the lives of ordinary people grew more difficult, the narratives emanating from the White House down continued to blame the deepening crisis—the rise in homelessness, the AIDS epidemic, the garbage-strewn streets, the turn to illegal economies—not on policy choices but on bad people. Crime, disease, and addiction were cast as moral failures rather than as the predictable consequences of political decisions.

Arguments such as these distracted the public from rethinking the true cost of stripping public coffers and actively widening the country’s income gap. In this sense, politicians interested in remaking the economy in ways more favorable to the rich did not merely rely on racialized resentment; they also helped ensure that anger would be directed downward, toward those even less fortunate than themselves.

White Americans in particular were offered a Faustian bargain during the Reagan ’80s: accept a thinner safety net, a harsher economy, and a more unequal society—but in return, receive the emotional satisfaction of seeing the “right” people punished by an ever-expanding criminal-justice system, and the tacit assurance that if they happened to visit their own frustrations on someone who did not look like them, that same system would protect them.

Ultimately, the fueling of racial fear did extraordinary political and cultural work, fixing public attention on crime rather than wage theft, on disorder rather than deregulation, on punishment rather than the public good. The Goetz saga proved just how effectively narratives of crime, and outright misinformation, could be used to discredit government, justify inequality, and legitimize extrajudicial violence—all while claiming the mantle of common sense.

When he was finally apprehended, Goetz claimed that he had no regrets for what he did. He made no apologies for wanting “to kill those guys; I wanted to maim those guys; I wanted to make them suffer in every way I could”—not because his victims were armed (they were not), but because he felt besieged and abandoned, and thus justified in striking back. He railed at the assistant district attorney who took his statement: The subway system was “a disaster,” crime in the city was “a disaster,” and the government in charge of all of it was “a disgrace.”

Goetz’s journey through the justice system reinforced the idea that his worldview had merit. A grand jury was convened despite extraordinary public pressure to simply let him skate, and then it declined to indict Goetz on attempted-murder charges. However, word got out that Goetz had confessed to gunning down the teens, had told detectives that “robbery had nothing to do [with] it,” and, what is more, had admitted to shooting Cabey a second time. A second grand jury was convened that indicted Goetz for a range of serious charges, including attempted murder. In the trial that followed, however, a jury of Goetz’s peers decided that, despite the evidence mounted against him, he was guilty of only the most minor gun charges he faced.

Goetz served eight months in jail. The message sent to the American public was unmistakable: It is perfectly okay for at least some people to take the law into their own hands.

Goetz’s case helped build the early architecture of conservative tabloid media and inflammatory talk radio. This seeded the ecosystem of social media and Fox News coverage that, together, perfected the art of viral outrage and the mobilization of economic anxiety for political ends. And although mainstream news outlets did not openly revel in—or explicitly justify—the Goetz shootings, they did privilege coverage of urban crime and disorder over careful, sustained attention to the structural conditions and policy choices that made cities less safe and eroded the material security of ordinary people.

Equally significant was the fact that the economic and cultural transformation that this country had undergone since the 1980s was never a project confined to conservative politicians. Politicians across party lines contributed to the steady dismantling of America’s social safety net and the stoking of resentment and rage, even as they worked to channel these for their own partisan ends. Bill Clinton would deliver the most devastating blow to welfare; Trump would perfect the art of turning fear into fury.

We are still living today through the long Reagan Revolution: A teenager crosses state lines with an assault rifle and is hailed as a patriot for killing protesters; a mob storms the Capitol, convinced that violence is necessary to “save” democracy, and is pardoned; an ICE agent shoots and kills a mother and is said to have acted in self-defense, despite all evidence to the contrary; politicians denounce crime while simultaneously cutting the very social programs that ordinary people need to survive and that help sustain safe communities.

[Gal Beckerman: Minnesota had its Birmingham moment]

Trump did not invent these dynamics; he inherited them. He did not create the legitimacy of white grievance. And he did not usher in a new age of white racial violence or escalating income inequality; he has merely decided to unabashedly incite the former and defend the latter.

As the country moves toward the 2026 midterms, the temptation will be to treat our current racial, political, and economic crisis as a sharp break from the past; to search for singular villains; and to imagine that a return to normalcy is just one election away. But political cultures do not change course simply because their most flamboyant representatives enter or exit the stage.

The hard and necessary task now is to reckon with how past moments such as the Bernie Goetz shootings of 1984 helped remake the boundaries of how much racial violence, inequality, hatred, and indifference we as a society are willing to quietly endorse or even embrace. Only by confronting our history honestly can we begin to understand why appeals to fear remain potent, why calls for punishment eclipse demands for justice, and why the promise of democracy has been so unevenly realized.

The post How the Bernie Goetz Shootings Explain the Trump Era appeared first on The Atlantic.