PARK CITY, UTAH — A hip-hop miracle was happening Friday afternoon in a mansion in the mountains of Utah.

The sole physical copy of the Wu-Tang Clan’s 31-track double album “Once Upon a Time in Shaolin” — the most expensive piece of recorded music in the world — was being played at a listening party for only the seventh time in its history, for about 40 people at the Sundance Film Festival. The party was something of a prison break for the album, which was first bought at a 2015 auction for $2 million by now-convicted fraudster and “Pharma Bro,” Martin Shkreli.

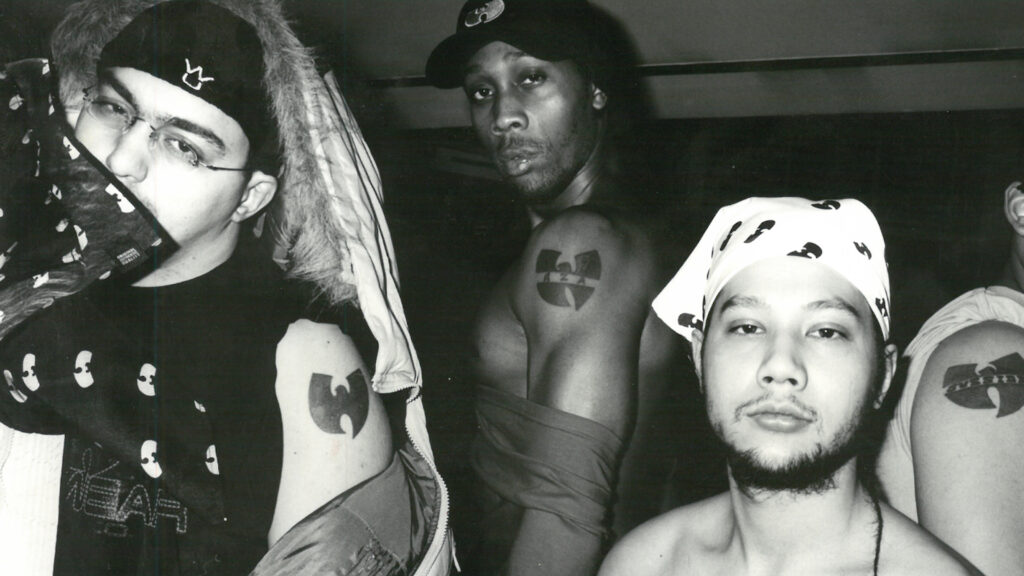

The album’s remarkable journey is the subject of “The Disciple,” a documentary from director Joanna Natasegara that debuted at the festival Thursday. Recorded in secret between 2007 and 2013, “Shaolin” features verses from every member of the legendary hip-hop collective (except for Ol’ Dirty Bastard, who died in 2004), as well as from Method Man’s closest rap collaborator Redman and Wu-Tang affiliate group the Killa Beez, alongside FC Barcelona players, the Dutch actress Carice van Houten and Cher. Yes, Cher. More on that later.

Wu-Tang’s de facto leader RZA and his “student,” Dutch-Moroccan rapper-producer Tarik “Cilvaringz” Azzougarh, conceived of it as an art project and a commentary on music being cheapened by pirating and the internet.

“We’ll make one single album, treat it like it’s the Mona Lisa,” RZA says in a podcast interview that opens the film.

And a Mona Lisa it nearly is. To this day, no downloadable or streamable copy of the album exists. It was burned as a two-CD album, deleted off the laptop and CD drive, sold at auction and presented to Shkreli in a handcrafted ornate silver box. During the sales pitch, RZA described it as “like owning the scepter of an Egyptian king.”

Three years later, the discs were seized as part of Shkreli’s conviction for securities fraud. The album then languished in a Department of Justice storage vault until 2021, when the federal government sold it to an anonymous group of digital art collectors for the equivalent of $4 million or more in cryptocurrency.

The art collective, PleasrDAO, has an elaborate plan to eventually make the album more public — while respecting an 88-year non-commercialization clause in the sale contract that means no one will be able to own a copy until 2103. They’re so serious about protecting the album from piracy that they didn’t allow Natasegara to use any of it in “The Disciple.” But they did answer the call when she asked for help celebrating the premiere, having the relic carted to Park City under heavy security so around 20 minutes of its two-hour-twelve-minute play time could be shared with the chosen few.

It’s “a Russian doll situation,” Cyrus Bozorgmehr, a British investor and friend of Cilvaringz who helped broker the original deal, told The Washington Post at the party. The album rests in a silver CD case inside a small silver box, inside a hand-carved nickel-silver box, inside a cedarwood carrying case wrapped in brown cow leather. Everything is embossed with the Wu-Tang “W,” including a specially carved key.

The party’s motley crew included hip-hop fans, journalists, friends of Pleasr and, randomly, “Moonlight” director Barry Jenkins, a friend of Natasegara who loves Wu-Tang so much that when he was 15-years-old in Miami in 1993, he took two buses to get their genre-defining “36 Chambers” from a Circuit City.

Everyone was ordered to put their phones in Faraday bags before the album was played.

“You don’t want the curse that’s going to come upon you if you don’t put your phone in a bag,” said a Pleasr spokesperson, Spencer Harrison. “This is sacred music. It comes from a sacred place.”

Harrison told the crowd that Pleasr thinks of themselves as “glorified smugglers” who had rescued “Shaolin” from a kind of hostage situation with Shkreli and the DOJ and wanted to honor the album by allowing the crowd to experience a small portion of it that afternoon on speakers “that cost more than the Ferrari I do not own.”

They began with a legendary 13-minute highlight reel that Cilvaringz had cut for the only presale listening session at the contemporary art museum MoMA PS1 in New York in 2015 to entice potential buyers. The crowd of less than 100 had included Arab sheiks and Leonardo DiCaprio’s art dealer. The Sundance crowd was considerably less rarefied.

The first moments were a tsunami of sounds — sirens, thunder, rich orchestration, Wu members throwing bars and shouting “the saga continues!” The crowd nodded their heads as the beats burst into the room, while Shabazz, a friend of Cilvaringz and member of the Killa Beez, occasionally shouted out commentary like, “Good times with good people!” (He’s on eight songs and five sketches on the album.)

Cilvaringz himself was absent. A Muslim who grew up working class in Amsterdam and now lives in Morocco, he “didn’t want to spend a week in ICE detention” given that every time he’s come to the United States previously he’s had to spend hours at border patrol, according to Bozorgmehr.

No member of the Wu was there, either, including RZA, who is an executive producer on “The Disciple” and had a scheduling conflict.

Other than RZA and Cappadonna, nearly all official Wu-Tang members declined to be in the movie. Some are still mad at Cilvaringz. “Shaolin,” it turns out, is not only deeply mythologized — but extremely divisive, even among the people who made it.

Toward the end of the 13-minute sampler, a blaze of horns and ethereal female voices swirled from the speakers. It was so good people looked like they might start dancing if they weren’t being so consciously cool.

Bozorgmehr excitedly whispered to The Post: “This is the Cher song!”

Cher is the album’s most random contributor “for the most insanely banal reason,” Bozorgmehr said. “[Because] Tarik emailed and asked her.”

She apparently did five takes and then shocked Cilvaringz by asking if they were okay or if he needed more.

Alas, the track was cut off before Cher’s hook began, but Harrison told The Post that her part begins with a member of the Clan introducing “the legendary Bonnie Jo!” — a 1964 pseudonym likely only known to Cher die-hards. Even without the hook, though, the crowd was so into it, they burst into applause.

Cher also performs on a skit track that the listening party didn’t hear in which RZA and Shabazz pretend to walk through Staten Island and encounter Cher as “a night character” talking to a police officer, Harrison teased. No one would reveal much, except to say she’s hilarious. Representatives for Cher did not immediately respond to The Post’s request for comment.

When the sampler ended, Pleasr played two full tracks from “Shaolin,” including the title song, which is filled with TV news audio about Staten Island gangs and overlaid with lush orchestration.

But it is Shkreli, not Cher, with whom “Shaolin” is most (in)famously associated.

“Martin happened to this story, and I don’t think anyone could have anticipated that,” Natasegara, the film director, said in an interview. “But in the grand scheme of things he’s kind of a blip.”

Shkreli was a relative unknown when the auction house accepted his $2 million bid for “Shaolin” in 2015, beating out billionaires who, Bozorgmehr said, had intended to play the album at museums or donate it to hip-hop archives at Ivy League universities.

The then-32-year-old investor and entrepreneur had been under investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission since 2009 for insider trading at his previous pharmaceutical company, which was suing him for $65 million. But he hadn’t yet risen to the infamy that would get him labeled “the most hated man on the planet,” as shown in TV news reports in the film.

Just three weeks after he locked his purchase of “Shaolin” with a binding deposit, he bought the rights to Daraprim, a medication used to treat toxoplasmosis in AIDS and cancer victims and immediately jacked up the price from $13.50 to $750 a pill. Two months after the album was in his hands, he was arrested on charges of an unrelated securities scheme, eventually being sentenced to seven years in prison.

RZA says in the film that he met Shkreli during the auction-vetting process and liked that he wasn’t the richest bidder, grew up in Brooklyn and had Albanian parents who were still working as janitors.

“Obviously, we did some background on him. He was being sued,” Bozorgmehr told The Post. “But you know, in America if you’re not being sued, are you even alive?”

Looking back, Bozorgmehr said, they should have been more wary of how Shkreli’s legal team kept stalling the deposit, saying he was buying a company — which turned out to be Daraprim. An attorney for Shkreli did not immediately respond to The Post’s request for comment.

“My constituents. They don’t buy Wu-Tang Clan albums,” Rep. Elijah E. Cummings (D-Maryland) scolded when Shkreli was called before the House Oversight Committee to explain his pill price hikes.

Sensing a PR crisis, Cilvaringz came up with a convoluted plan in which Shkreli would start a fake Twitter beef with the Wu-Tang, then sell the rights to “Shaolin” to the fans.

Shkreli was enthusiastically on-board, but went wildly off-script, Cilvaringz says in the film, relentlessly sending insults to Clan members who weren’t in on the scheme.

When the FBI raided Shkreli’s apartment in December 2015, they found replica AK-47s that, Cilvaringz says in the film, he’d been planning to use in an off-script video in which he’d tell the Wu-Tang Clan “to be ready to join their brother ODB [Ol’ Dirty Bastard] in heaven.”

As part of his was prison sentence, Shkreli was ordered to forfeit $7.4 million in assets, including a Picasso drawing, a machine made by Alan Turing, and “Once Upon a Time in Shaolin” that were to be sold, with proceeds going to the investors he defrauded.

As told in “The Disciple,” the album is really a story about a poor Muslim kid from Amsterdam with an almost preternatural level of determination who found kindred spirits in a rap group of martial arts nerds from Staten Island.

Cilvaringz flew from Amsterdam to New York three times starting in 1997 when he was 18, trying to join the Killa Beez, one of several affiliate groups that had grown up around the Wu in the four years since their era-defining 1993 debut album “Enter the Wu-Tang (36 Chambers).”

And then it miraculously happened. Cilvaringz found a mentor in Shabbazz after calling his phone number listed on the back of his album. He became friends with RZA’s sister after wandering into a nail salon she owned. In 2000, RZA signed him and his friends to the Beez. He toured with Wu-Tang, pitched the idea of a Killa Beez world tour in 2003, and eventually released a 2007 solo album featuring guest appearances from Wu-Tang members before deciding he preferred being a producer.

While at the Egyptian pyramids on the Beez tour, Cilvaringz and RZA had discussed the idea of making an album as rare artifact. Life got in the way. The idea was shelved. But RZA encouraged Cilvaringz to get out of his head, approach Wu-Tang members to rap over his beats, and just record stuff.

That’s where some members of the collective, looking back, say Cilvaringz misled them.

“When I was approaching everyone to record, I wasn’t trying to make a Wu-Tang record,” Cilvaringz explains in the movie.

With RZA’s blessing, Cilvaringz called Wu-Tang members individually to pitch them on the album-as-artifact idea. The majority signed on. Then the Shkreli of it all happened.

“RZA, obviously, is fully involved. I think the other guys, they’re slightly bruised by how it all played out,” Bozorgmehr said at the party.

Some of the beef, Cilvaringz says in the movie, was about money. He’d paid everyone as guest artists for an affiliate project, which is much less than they’d get for a Wu album. He said he didn’t go back and negotiate out of fear that the whole project would have fallen apart.

Method Man, arguably the most famous member because of his prolific acting career, was the harshest critic. The film shows Meth on a podcast explaining that, once “Shaolin” turned into a Wu-Tang album, some of the members felt duped. If they’d known it was meant to be preserved for history instead of a one-off guest appearance, they would’ve taken more time. “They might have been a little more artistic with it,” he said.

“I can’t stand Cilvaringz,” Method Man says in a clip in the film, calling the album “a gimmick.”

For Pleasr, which Harrison describes as “an anonymous art collective of people who made a bunch of money in various ways, like crypto,” the mission to preserve the original vision of the album is deeply personal. As soon as their founder, Jamis Johnson, learned the DOJ was auctioning the album, he spearheaded a lightning-fast fundraising effort to acquire it, believing they had to be its custodians at all costs. He died in 2025 after a serious injury from an ATV accident.

“The Disciple” presents Pleasr as heroes intent on rescuing the project from Shkreli’s ignominy and the ephemerality of the digital age. They have, at least, rewound some of the chaos that followed the album’s creation. In 2024, the group filed a lawsuit that resulted in a judge ordering Shkreli to hand over any copies he may have made of the album, restoring a degree of sacred status to the double disc.

Their goal, Harrison said, is to follow through with the vision that RZA and Civilringz set forth, of creating a piece of hip-hop music that people need to make a pilgrimage to hear. They are “working actively” to bring the music to the public, possibly in the form of museum exhibits.

The saga continues.

The post The bizarre story behind the world’s most expensive album appeared first on Washington Post.