Three years out of law school, in 1990, David Goldschmidt landed the kind of assignment most young corporate lawyers only dream of: taking a company public.

When a senior partner at the venerated New York law firm Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom told him to “run with” biotech company Regeneron’s IPO, his career changed.

Goldschmidt sweated his way through writing the prospectus, translating the company’s scientific ambitions into plain language for investors. Regeneron raised twice the expected amount in the initial offering.

The victory was volatile. The stock swung sharply after the IPO, prompting shareholder lawsuits. A federal judge dismissed the cases against Regeneron, finding the company’s disclosures to be accurate and legally sufficient. And for Goldschmidt, the trial by fire taught him something.

“I could do this,” he remembers thinking.

Goldschmidt rose through the ranks to become a partner and, eventually, the global head of Skadden’s capital markets practice, advising companies on raising capital in the public or private markets. His name appeared routinely on the opening pages of S-1 filings, including those of Casper, Match Group, and Rivian Automotive, whose $12 billion raise was one of the largest US IPOs in history. In 2025 alone, the hundred-person Skadden group handled more than $300 billion worth of transactions.

Goldschmidt retired last month after 37 years at Skadden, ending a tenure that made him a rare constant in an industry increasingly defined by churn.

While he stayed put, the ground beneath him did not. From his perch at Skadden, the fourth-highest-grossing law firm in the country, Goldschmidt worked through a technological revolution that shifted the legal industry from analog to algorithmic.

He’s not convinced smarter machines make for better lawyers.

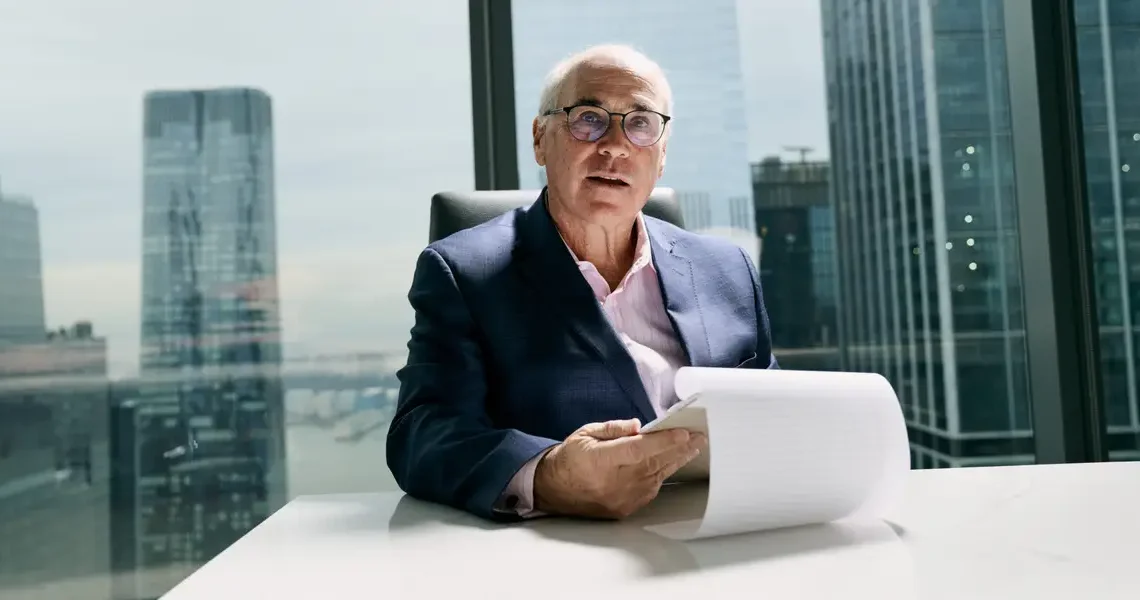

I met Goldschmidt two weeks before he retired, in a conference room high above Manhattan’s West Side. The 62-year-old looked relaxed in a tailored navy suit. He asked for a coffee, and within minutes, a pair of staffers set up a full barista station on the credenza. We each poured, and I asked him when he decided he wanted to be a lawyer.

“Five years into practicing,” he said.

Goldschmidt went to law school unsure about what kind of law he wanted to practice, driven only by a curiosity about “how the markets work,” he said. At first, he purposely avoided Big Law, starting at the smaller, white-shoe firm Breed, Abbott & Morgan. On his first day at the New York office, a woman in HR led him on a meet-and-greet with the partners. With each knock on a partner’s door, the mood darkened.

At one office, the woman began her script. “How are you doing today? This is Mr. Goldschmidt. He’s starting today —”

“How do you think I’m doing?” the partner cut in. “The market’s down 22%.”

It was October 19, 1987, Black Monday, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average plunged more than 500 points, wiping out roughly half a trillion dollars in market value.

The crash was violent but brief, and soon leveraged buyouts and mergers exploded. For law firms working those deals, the frenzy translated into enormous amounts of work. Goldschmidt realized that the “genteel” lifestyle he had sought was an illusion.

“Regardless of what size law firm you work at, you’re going to work hard,” he said. Within his first year, he left to join Skadden’s capital markets practice, securing a front-row seat to the global economy that he would occupy for the next 37 years. He fell in love with the fervor of the environment and the people hustling beside him.

The intensity of the work hasn’t changed. The work itself has.

When he started, his desk held a LexisNexis terminal, an angular box with a built-in keyboard used for case law research; he used it as a surface for Post-it notes. He wrote documents longhand on a legal pad, handing them off to a typing pool staffed by, as Goldschmidt recalls, “aspiring actors.”

Editing a document meant two associates sitting side by side with the new and old versions, reading the first word of every line aloud to mark where the draft had changed. He dashed to meet the mail courier at 9 p.m. to make sure clients had the documents in the morning.

Goldschmidt saw this as valuable repetition, learning through what he calls “sweat equity.” He didn’t study judgment; he accumulated it. Even as Microsoft Word replaced typing pools and due diligence moved online, much of the mental work of synthesizing information remained.

Those reps became part of Goldschmidt’s value to clients, said Jeffrey Horowitz, a longtime Bank of America executive who worked with him across multiple transactions. “You’re getting long-term advice — grounded in history and a real relationship,” he said.

Regeneron remains a Skadden client, now a roughly $77 billion biotech. Its cofounder and CEO, Dr. Leonard Schleifer, remembers Goldschmidt as a “workhorse,” citing his attention to detail and command of the law.

Now, with the legal industry on the cusp of another shift, artificial intelligence is beginning to absorb some of the routine work that once consumed junior lawyers’ time. Goldman Sachs has said the technology could someday automate 44% of legal work.

Goldschmidt’s own introduction to the technology came from his son, then a Big Law associate. He gave him a demo of a legal software called Harvey, which could draft and find answers in documents that might take an associate hours of slogging. “It just blew me away,” Goldschmidt said.

That efficiency raised a fundamental question. How do you train young lawyers when machines do the work for them?

For Goldschmidt, the value of sweat equity isn’t just hard work. It’s the intellectual struggle of problem-solving. Learning, he said, happens when you “hit a brick wall and veer off” to find another path. If new tools surface answers instantly, he worries, junior lawyers may lose not only the habit of wrestling a question to its conclusion, but the legal fundamentals needed to recognize when a chatbot is hallucinating or getting it wrong.

Still, Goldschmidt is careful not to romanticize the past. “It may be easier,” he said. But law, he argues, has never been a profession where fulfillment comes from sitting at a desk and simply executing tasks.

“A fulfilling career,” he said, “is going out there, stretching, meeting people, learning — seeing what’s around the bend.”

Inside Skadden, Goldschmidt said, there’s a saying: Walk through walls for the client.

That ethos only intensified as new tools arrived. Legal work, after all, is a service business. Email and cellphones reset expectations for speed and responsiveness. Now, clients are pushing law firms to adopt artificial intelligence in the name of more efficient service. Skadden pays for its lawyers to have access to Harvey and other tools used for research, drafting, and document review.

For Goldschmidt, even the early technology was a “double-edged sword.” A BlackBerry meant he could finally go to a movie on a Saturday night without worrying he might miss a call. But it also meant there was no longer any real off-switch. The culture didn’t always allow lawyers to check out.

Goldschmidt remembers around that time reading an article about email that described how Bill Gates would sit down at his computer at night and respond to his messages in one sitting. “How lucky is that guy,” Goldschmidt remembers thinking, “that he can wait till the end of the day?”

As Goldschmidt prepared to retire on New Year’s Eve, he remained optimistic about the next generation of lawyers, provided they remember that the job requires more than just prompting chatbots. Looking back on the shift from legal pads to large language models, he offers a final assessment of his four decades in the arena — not as a protagonist, but as an essential witness.

“I may not have invented anything,” Goldschmidt said. “I may not have started a company that changed anything. But I had a front-row seat to all those people, those companies, who did.”

Melia Russell is a senior correspondent with Business Insider, covering the intersection of law and technology.

Read the original article on Business Insider

The post A Skadden veteran’s uneasy take on smarter machines appeared first on Business Insider.