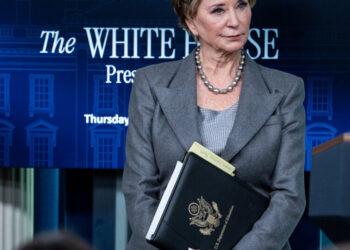

Denyce Graves made sure to stick a few tissues into a pocket of her costume for the Saturday matinee of the Gershwins’ “Porgy and Bess.” It was the 158th — and the final — time she would perform at the Metropolitan Opera. She was sure she was going to cry.

“Denyce Graves,” said Peter Gelb, the general manager of the Met, in a simple introduction, as the curtain rose for the second act to show Graves surrounded by the opera’s cast. The applause, from the stage and from the packed hall, seemed as if it would never end. She pulled out those tissues.

“Peter, I knew I was going to cry,” she said, her voice quavering as she received a plaque commemorating her as one of “opera’s outstanding artists.”

It was a career that almost didn’t happen.

When Graves was 24, a doctor told her she wouldn’t sing again. It was just three years after she made her professional opera debut at the Tulsa Opera. She resigned herself to a life off the opera stage.

“He discovered that I had a real imbalance in my thyroid that was creating some havoc,” Graves, 61, said in a lounge at the Metropolitan Opera recently, pulling down the top of her dress to show the still visible signs of an enlarged thyroid. “And he told me that I would not be able to have a career.”

The doctor was wrong. A year later, Graves, a mezzo-soprano, agreed to audition for the Houston Opera’s “Carmen,” and was cast as Mercedes. And for the next 38 years, she persevered through health challenges — the thyroid, a hemorrhaging vocal cord, goiters in the neck, cluster headaches — to become one of opera’s top singers.

On Saturday, the crowd cheered at her spirited portrayal of Maria, the keeper of the cookshop on Catfish Row, a relatively small but driving presence in the sad love story of Porgy and Bess. Still, Graves will be more remembered for lead roles like Dalila in Saint-Saens’s “Samson and Dalila,” and especially for the title character in Bizet’s “Carmen,” which she sang in her Met debut in 1995. By that point, she was a big enough star to be featured on “60 Minutes” on CBS. Introducing the segment, Morley Safer said, “This is the result when guts, discipline, talent and beauty all combine in one happy accident.”

Graves was raised by a single mother in southwest Washington D.C. She began singing at a young age because her mother wanted to keep her three children busy until she returned home from work: Thursday was for singing. “It’s a shame that nobody hears you do this,” her mother told her.

Graves has always kept a home in Washington, and her roots there run deep. Over the years, the capital turned to her at difficult moments. She sang “America the Beautiful” and “The Lord’s Prayer” at Washington National Cathedral after the attacks of Sept. 11 and Gene Scheer’s “American Anthem” at the memorial service at the U.S. Capitol for Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a lifelong opera fan and friend.

Graves said she had a few low-profile appearances left in her, but for now, she is moving to a life of directing and running the Denyce Graves Foundation, dedicated to social justice and the arts. We spoke twice; once a few weeks ago, and again, in her dressing room, after she stepped off the stage on Saturday. These are edited excerpts from those conversations.

After all that applause, I trust you’re not having second thoughts?

No! But I thought, I’m really, really retired from this now. That was so final. I am going to be directing and I love that. And I’m very excited not to have to worry about my voice.

It sounds like you have spent a lot of you career tending to — and worrying about — your voice.

Everything you do impacts what happens with your voice, everything. Talking to you now. Being out in the cold. What I just ate — I just ate an orange, right? Like acid, like all of these different things impacts the quality of the instrument. Everybody knows what it feels like to have a really great voice lesson or to have a really good performance and we’re always sort of chasing that.

What made you decide the time had come to retire?

I’m in my 62nd year. And when this offer came to sing this Maria in “Porgy and Bess,” I thought, how perfect. The very first opera contract I got was for “Porgy and Bess.” That was with Ed Purrington at Tulsa Opera.

Can you talk about being asked to sing at the service commemorating 9/11 at the National Cathedral?

I didn’t really understand at the time the magnitude of what that service going to be. I looked down, and said, That looks like President Carter. And I said, Oh my God, is that President Bush? And that’s President Clinton. It changed everything for me after that. Laura Bush came to talk to me. She’s become a friend.

Some years ago you said that your interest in opera came after a class trip to the Kennedy Center.

That’s true.

Considering what’s going on there now, would you sing at the Kennedy Center now?

Well, I just did. We did “Porgy and Bess” there. In May of last year.

You were supposed to direct Scott Joplin’s “Treemonisha” there, but now that the Washington National Opera has pulled out of the Center, it is going to be performed at Lisner Auditorium. How do you feel about that?

I would have liked to have seen if there could have somehow been a way to make it work at the Kennedy Center for a number of reasons. I mean, things are going to be in an incredible chaotic state in terms of, you know, is there a costume department? What about the sets?

But I know that they have every intention on going forward with everything. And I think there’s a tremendous amount of support in the community for them as well. I’m happy to see that.

Are you worried about the future of the Kennedy Center?

I am worried. It’s such a treasured and beloved place.

What do you think about artists who say they will no longer perform there?

There’s a part of me that understands that. On the other hand, I obviously grew up as a Black woman, before that a Black girl. And there were so many restricted doors for us coming up. And I had to learn to just soldier on, no matter the situation.

Whatever your conviction is, I see it a little bit as a luxury to be able to say, well, absolutely not: I’m not going to do that. But I admire people who take that kind of stance.

You have been best known as Carmen. “This is a problem for my career,” you once said. “I want people to come to the theater because I’m singing — not because it’s ‘Carmen.’”

I was at Covent Garden singing “Carmen” with Plácido Domingo. We were doing the opera inside, but they were showing it outside. After the opera was over, Plácido said, “Denyce, let’s go outside and thank everybody for watching the opera.” I came out, and people said “Carmen, Carmen, come sign my program and take a picture with me.” He came out. And they said, “Plácido, Plácido.”

You have said that you didn’t want to be thought of as a Black opera singer.

If I walk through the door, that’s what you see: a Black woman. That is who I am, that is my container in this life at this time. My issue with it is that we don’t say the white soprano Erin Morley. You don’t say the white mezzo soprano Frederica von Stade.

How do you think about the allegations of sexual misconduct regarding Plácido Domingo and James Levine, both of whom you worked with?

I certainly don’t condone it. And I don’t excuse it either. And I know that we’re all flawed beings and that particular flaw doesn’t not equal the whole of who that individual was. It’s a big, terrible flaw, for sure. But it doesn’t take away from the beauty — what they are, what they gave, what they built at this opera house, around the world.

Were you shocked to learn this about them?

No. Not at all.

There’s concern about aging and declining audiences and a loss of passion for this art form. How do you think about the future of opera?

We saw something extraordinary happen after Covid, when for the first time in the history of the Metropolitan Opera the theater was shut down. I remember that we came back with the opening of “Fire Shut Up in My Bones” [a new opera by Terence Blanchard], and people came out. And so I think that the opera administration was looking at that saying, “Oh my goodness, look at the appetite that people have for these new stories.”

You know, the ABCs, right? “Aida,” “Bohème” and “Carmen.” They aren’t going to go anywhere. And I love those operas. But at the same time, there’s a real hunger for new voices and new storytelling.

Adam Nagourney is the classical music and dance reporter for The Times.

The post Denyce Graves Says Goodbye to the Opera Stage After 40 Years appeared first on New York Times.