Americans are deeply pessimistic about their economic future, driven by financial anxiety among all but the oldest Americans and by a widespread belief that a middle-class lifestyle is out of reach for most people, a New York Times/Siena poll found.

While a majority of people said that they could afford basics like rent, gas and groceries, most said they worry about the costs, and there was a pronounced sense that it has become more difficult, if not nearly impossible, to get ahead in America today.

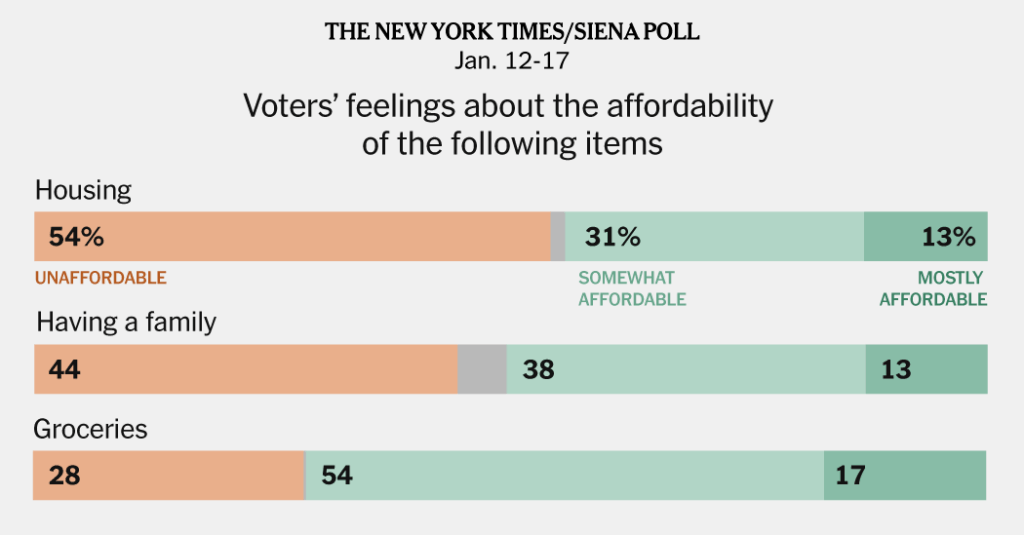

Majorities of voters said they do not feel confident in their ability to pay for housing, retirement and health care, all traditional staples of a middle-class lifestyle. Separately, more than half said housing and education are now so expensive that both have become unaffordable.

Those rising costs have shifted perceptions of America as a place of upward economic mobility dominated by a comfortable middle class. Two-thirds of voters said they now think a middle-class lifestyle is out of reach for most people, and 77 percent say it has gotten harder to achieve than a generation ago.

The economic worries persist across geographic, gender and racial lines. The only voters who seem less stressed economically are those over age 65, who express far fewer concerns about costs.

Taken together, the findings illustrate how economic anxieties, feelings of insecurity and a bleak outlook for the future have continued to weigh on most voters despite a booming stock market and resilient consumer spending.

Such cost-of-living concerns have emerged as a major issue in the midterm elections and a notable weakness for President Trump, as he works to push his agenda through Washington. Fifty-one percent of voters said that Mr. Trump’s policies had made life less affordable for most Americans

Prominent Democratic candidates in marquee races embraced a message focused on “affordability” to sweep to victory in the elections last year. Already, the party has made the issue a centerpiece of its midterm campaign, attacking the Trump administration over the costs of housing, health care, groceries, child care and other household expenses.

But the survey indicates that the issue is not lost for Republicans. Americans were divided on whom to blame most for the nation’s economic challenges.

Thirty-one percent said Mr. Trump was responsible for the biggest challenges facing the U.S. economy, while 35 percent said it was former President Joseph R. Biden Jr., and 33 percent said neither president was responsible. Independent voters were equally likely to place blame with Mr. Biden and Mr. Trump.

The polling also offered hints that the current economic mood, while dour, may be slightly brighter than it was at the end of Mr. Biden’s term. Thirty-one percent of voters think the economy is better off than it was a year ago, an improvement over the 21 percent who said the same in April 2025. Twenty-nine percent rated the economy as “excellent” or “good,” a seven percentage point increase from the fall of 2024. But 70 percent still describe the economy as fair or poor.

Nearly 60 percent of voters said they worry about affording the very basics — rent, gas, routine bills and groceries — and 11 percent said they could not afford them at all.

Nathan June, an engineer from St. Louis, said he can afford basic expenses and save some for retirement but has little “level of buffer” for emergencies.

“Even though I make more than my parents have, I struggle more than my parents ever did,” said Mr. June, 41, a father of three young daughters with a net annual household income of about $160,000. “For the amount of work that we’ve put in, it really seems much more difficult than it should be.”

Inflation, while far down from the highs after the pandemic, continues to nag at households in the form of stubbornly high utility and food prices. Housing costs and rents, typically the biggest slice of a household budget, have soared above what many families can stomach.

Only a small fraction of voters — 14 percent — feel they are actually getting ahead financially. Even many people making more than $200,000 a year, a household income in the upper ranges of American families, expressed concerns about their long-term economic stability and the cost of health care. Ten percent of voters making more than $200,000 a year said they did not think they could afford the cost of retirement.

Much of the economic pessimism tracks along generational lines. Younger Americans expressed far more financial anxieties and a bleaker view of their economic futures.

Half of voters under 45 described themselves as generally worse off financially than their parents were at their age, and just 10 percent feel they are getting ahead financially. A majority of those voters say the cost of having a family has become unaffordable. And as traditional pensions disappear and Social Security faces a financing shortfall, 75 percent of voters under 65 say they cannot afford the cost of retirement or feel insecure about it.

Voters over age 65 consistently expressed far less anxiety about costs. When asked what they worry about affording, 24 percent said “nothing.” Nearly 60 percent of older voters described themselves as “holding steady” financially, while 40 percent of voters under 30 said they were “falling behind.”

Older voters likely don’t face the same economic pressures as younger generations. Most receive health care through Medicare, bought homes in a far cheaper market and, with grown children, do not face record high costs of child care and education. But 26 percent said they worried about affording medical and health care costs.

Nearly two-thirds of voters over 65 said they can afford the life they feel like they should be able to afford, while a whopping 75 percent of voters under 30 said they cannot.

Michael McCarthy, a retired high school computer drafting teacher from outside of Buffalo, N.Y., described himself as doing better financially in his retirement than his parents in theirs.

“My wife and I were both teachers, so we both had decent incomes and we saved,” said Mr. McCarthy, 77. “I don’t want to buy a vineyard, so that’s out. I don’t need a yacht. So that’s out. If I want something, I buy it. But I don’t have a lot of wants.”

Housing topped the list as the biggest financial concern for most voters under 65, including more than half of voters under 30 who said it was the thing they worry most about affording.

While 70 percent of older voters said that they already have the home they’d like to own, more than half of voters under 30 said such a home was “out of reach.”

For young voters, the anxieties span the political spectrum. Majorities of young Republicans and Democrats said housing and education costs had become unaffordable and that they did not feel secure in being able to afford retirement.

Tasen Millspaw, 21, an Amazon delivery driver from Ogden, Utah, said that his grandmother had told him that decades ago even people earning minimum wage could save and afford a reasonable place to live. While he now earns more than three times the minimum wage, he said, “I still have to live with other people in order to just pay rent.”

Mr. Millspaw added: “It’s harder to be middle class nowadays.”

Lisa Lerer is a national political reporter for The Times, based in New York. She has covered American politics for nearly two decades.

The post Voters See a Middle-Class Lifestyle as Drifting Out of Reach, Poll Finds appeared first on New York Times.