Subscribe here: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | YouTube

In this episode of Galaxy Brain, host Charlie Warzel speaks with the reporter Ryan Broderick about how the internet’s fragmentation of attention and facts has bled into real-world political violence in Minneapolis this month. From the viral spread of a right-wing video about day-care fraud in Minnesota to the aggressive ICE activity in the region that followed, the episode charts how online content routinely shapes government action and public perception.

Broderick, who spent days in Minneapolis after the shooting of Renee Nicole Good, describes what he saw on the ground: how protesters and law enforcement are behaving differently this time around, especially with regard to filming and digital organizing. The conversation explores a novel and concerning feedback loop where what happens online spurs real-world interventions, which then generate more content for audiences elsewhere, compounding division and uncertainty about what’s true.

The following is a transcript of the episode:

Charlie Warzel: Going back to Renee Good, the idea that there was an ICE agent that was filming while involved in this life-or-death—you know, supposedly for him—situation, right? You’re claiming that, but at the same time you’re using your phone to document this.

Ryan Broderick: Yeah, I’ve never had a law-enforcement agent pull up their assumedly personal smartphone and film me. I’ve never seen that—to have them just, like, have a gun in one hand and a phone in the other blew my mind. And I just have to wonder, Where is that content going? Where are those photos and videos going?

Charlie Warzel: I’m Charlie Warzel. Welcome to Galaxy Brain. Around 2015, I started to do a lot of reporting on the ways that the internet was causing a societal rupture. It’s possible, I think, that for Americans—and maybe for everybody—that there’s never been a true shared reality. That we have always been living, in some respect, in filter bubbles of our own making, even before the internet.

But as the world really came online, and as our politics and our culture were uploaded to these social networks that are essentially built for viral advertising, the shreds of our monoculture were consumed by a constellation of content, much of it algorithmically fed to us, and that something changed in that moment. I wrote back in 2017 that it felt like that was the first year—in the first year of the [Donald] Trump presidency—where it just became obvious that Americans were effectively living in two universes, and each one was propped up by their own information ecosystems.

Around that time, too, I was also writing a lot about the ways that technology would continue to blur and make it harder to understand what was real and what wasn’t real. In 2018, I wrote this piece where I spoke to a number of researchers, including a man named Aviv Ovadya. And he specifically warned of this infocalypse, is what he called it—an information apocalypse—basically a future where AI tools and craven hyperpartisan actors on this algorithmic internet that’s completely fragmented and fractured and tech-powered would allow anyone to cast aspersions on any event or anything or any fact. People could just fake anything. And they argued that would eventually create this realm where, to borrow a phrase from the researcher Peter Pomerantsev, nothing is true, and everything is possible.

People, they said, would be radicalized. They’d be overwhelmed. They’d be hopelessly divided, and they’d be sad. But mostly it would get to the state where when you can’t figure out what’s true—when everything is just this information war—that eventually you just start to tune out. And this was all pre-pandemic. It felt very plausible, but the generative AI tools weren’t out yet. They were pretty crude. They were pretty bad.

So there was this feeling that it was plausible, but it still felt so futuristic.

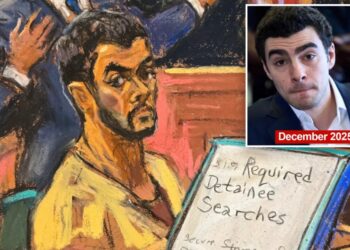

But today, it kind of feels like we’re living in that future. Just in January, just this month, it feels to me—as someone who’s covered this for a long time—that we are living in a pretty straightforward depiction of what the worst-case, post-truth, information-apocalypse scenario was, of the people who were warning about it in the late 2010s. I mean, if you just think about this month, you have X and Grok and this major platform generating and distributing this AI nonconsensual sexual-abuse material. And having it viralized and weaponized to intimidate and harass minors and women. You have a terminally online government. And you have the officials marshaling the resources of the military in service of propaganda to perform for this imagined audience online. And that’s all happened with the U.S.’s military invasion and capture of [Nicolás] Maduro and all the content that has been posted alongside it. You have a YouTuber named Nick Shirley, who at the end of last year posted this video online alleging daycare fraud in Minnesota involving the state’s Somali population. That video exploded online and eventually led to a chain of events that led to the Trump administration deploying a higher level of enforcement of ICE en masse to the Twin Cities. This, of course, culminated in an increased amount of raids and ICE agents in the street in Minneapolis. And, ultimately, in an ICE agent shooting and killing Renee Good in her car. It was captured on video. That video quickly spread online, with people analyzing it from multiple angles There have been tons of protests in the ensuing weeks. So much of that has been captured online. Protesters filming ICE; ICE agents filming protesters. Incredible amounts of content on social networks of people being abducted or arrested or having tear gas deployed on them.

It is this situation where it feels like there’s this battle being fought through everyone’s phone. It feels a bit like a hinge point, and it feels like there is a—despite all of the political issues happening here—that there is a technological issue, that this is all a bit of a culmination of things that I’ve been following for a really long time. Somebody else who’s been following that in some cases alongside me is Ryan Broderick. Ryan Broderick writes the Garbage Day newsletter and is the host of the Panic World podcast. Ryan and I worked together at BuzzFeed during the 2010s for quite a while, covering the ways that the internet changes how we behave politically, and the way that it can impact some of these political movements. Ryan was someone whom BuzzFeed sent to cover all kinds of online and offline protests around the world. He’s been to 22 countries, reported from six continents. And he’s been on the ground for close to a dozen referendums and elections. Ryan recently came back from observing all the protesting in Minneapolis, and he joins me today to talk about what happened in Minnesota, what is happening, and the ways in which all of this can be linked and not linked to an extremely online society. He joins me now.

All right, Ryan Broderick, welcome to Galaxy Brain.

Ryan Broderick: Thank you for having me. I’m so excited. Congrats on becoming a podcaster. I’m really sorry that happened to you.

Warzel: I know. It’s everything I ever wanted—to just be mocked on YouTube and across multiplatforms. It’s lovely.

Broderick: That’s right. It’s about discovering new audiences that hate you. That’s what modern life is.

Warzel: That’s what we’re doing. Man. Well, I appreciate it. I want to talk to you about your reporting. You went to Minneapolis just a few days after an ICE agent killed Renee Good, and you were there for protests around the city and around the federal building. I want to start with—just tell me what it was like to be on the ground in Minneapolis for those few days.

Broderick: It’s very surreal. I’ve definitely come back with a profoundly different take on the seriousness, I would say, of the Trump administration. I think you and I have been having essentially one conversation for a decade. Which is like: How seriously should we be taking this stuff? Is this just like internet chatter, or is this a real existential threat to American democracy? And now that I’ve kind of seen the whole hyper object—you know, from internet content down to what is effectively an occupation of an American city—I think we need to take it very seriously. I’m pretty freaked out.

Warzel: Yeah. So give me a sense of, because you were kind of there in the beginning of this. I mean, things are still going on. There’s still people protesting. This is not a finished movement in terms of the raids in the Twin Cities. But since you were there in the beginning, tell me how you saw it evolve, in terms of both the protesters and ICE’s participation there.

Broderick: Yeah. So, we saw the news come across social that Renee Nicole Good had been killed in Minneapolis. And my producer, Grant, and I—we work on our show Panic World together—so we started talking to our partners on our podcast, which is Courier News. And I was like: “Look, I think this is big. We should do this.” And so we went. Basically, we were there 24 hours after she was killed, and we spent the weekend there. And, you know, if we had had the money and the resources, I’d still be there.

I think it is still unfolding and developing. But the point of our trip was not to—I keep stressing this in everywhere I talk about this—like, our point was not to re-report what people in Minnesota are already covering. They have a great local news scene. But there are specific questions that I think people like you and I ask of events like this, that local news doesn’t have the bandwidth or even the interest in asking, or know. And so it was really useful for me to just follow the action for four or five days and see how this community is using technology, how they’re responding to technology, how the internet is shaping the events on the ground. And I think we did that, but yeah, I think this is going to become just sort of like one of those long political quagmires that happens during Trump administration. Like, it’s just going to drag out.

Warzel: So give me a sense of the level of online-ness of these protests. Give me a sense of how the tech is shaping it. I think for the first, part of the question is: A lot of modern protest movements are very online organized, via social networks and different apps and things like that. This one seems to be, based off of the reporting I saw a little bit. You read that a little bit differently.

Broderick: Yeah. I mean, so—I was trying to think back of what was the last protest that I went to. And I went to a few during 2020. But the last sort of movement like this that I saw close was the Hong Kong democracy movement in 2019. And I was there for what would eventually be—I think no one knew at the time—but it was the last time they protested before China really cracked down. And that was totally online. Like, I watched a completely silent crowd moving in perfect sort of organization using Telegram. Which I was really like, freaky. lLike these Gen Z kids had figured out how to use these messaging apps in a way that I’d never seen before. Minnesota is not like There’s a hashtag, and we’re all spray-painting it around the city, and we’re wearing Guy Fawkes masks and shit. No, none of that. It is people who are, if they’re using apps, they’re using Signal. They’re using a walkie-talkie app; I think there’s a couple that they’re using to organize ICE monitoring. And they’re finding out about protests and demonstrations by just going to them. Like, we interviewed countless people who are like, I was on my way back from work, and I saw this, and I’m mad. So I came by. And we talked to people who’ve never been to a protest before in their lives. Like, you know, we’re talking like middle-aged people who are like, I don’t have any real political thoughts, and this is insane. And I’m going to come out, and I’m going to protest. So it was very different. And to compare that to the other side, which is extremely online, was a total inversion of everything I’ve seen in my career. Like, it really stopped me in my tracks.

Warzel: Let’s talk a little about that. Because something striking that I saw in your reporting, just like coming across on social media as you were like sharing in the moment, was—

Broderick: You didn’t read the post?

Warzel: Well, I always read the posts, but in the moment.

Broderick: No, you just read the Bluesky post. See, I know. I get it. Yeah.

Warzel: I mean, you think I’m gonna pay for a subscription? I mean, come on.

Broderick: No, I wouldn’t. Yeah. Of course.

Warzel: Something that I saw, though, was you were videoing a couple of what seemed to be content creators, like stepping out of ICE vehicles. Or at least government or unmarked government-looking vehicles. Filming, and then like popping back and not addressing themselves. What did you see in terms of creators, influencers who were sort of either deployed by or administration adjacent? Or supported by the administration, you know, in some facets?

Broderick: So the specific incident you’re talking about, with the guy who jumps out of the ICE vehicle. Basically, this woman gets arrested by ICE because she punches their window as they drive by. Like, didn’t damage the window or whatever, if anyone cares. But they jump out of the cars, they pull up, and they just tackle her to the ground. And then right behind them—coming out of the same car—was a guy in plainclothes, like a nice suit. you know, like sunglasses. And he’s smiling, and he’s filming the whole thing.

And I am screaming at him, like, Who are you? Why aren’t you in uniform? Who are you with? Where’s that video going? I later find out that it’s a Fox News correspondent that was on a ride along with ICE. But there was also just like a ton of other right-wing networks that are around. Like, the Daily Wire was filming people. And OAN and NewsNation and all the baddies. There were also a group of YouTubers, livestreamers, content creators that were running around the city, harassing people. And they had a much less official connection to ICE. But obviously whenever they would rile up the crowd, the ICE agents would come out and protect them from the crowd.

And that culminated in last weekend with the leader of that group: Jake Lang, a January 6 insurrectionist. He tried to burn a Quran on the steps of the Minneapolis City Hall. And got his ass beat. And so it’s—that, to me, is much more connected to what we’ve already seen in Trump administrations. Like, the roving gangs of content creators that are just, you know, trying to antagonize leftists and make them look violent on stream. But the fact that ICE was so brutal to the protesters while also basically running defense for these content creators … they weren’t trying to hide it, in the way that you know, police forces were in the 2020 protests.

Warzel: Well, let’s talk a little bit about what you saw from ICE agents. Because there is this element, and I want to get into it in a second, of this content-creation spectacle. But in terms of you saying you came back from this, and it’s very obviously understandable why you would feel this way. Like, I’m freaked out about this. And the seriousness of what’s happening there and what the administration’s doing. But can you just describe for me—and for people, you know, who may not be mainlining this stuff on their phones—what you were seeing from ICE that was so disturbing, or the way that they were treating protesters.

Broderick: They don’t even seem to understand why they’re trying to control the crowd. They don’t, really. I’ve dealt with, you know, antagonistic police forces in protests before. And there’s a rhythm to it. There’s sort of like an assumption that like, If you do this, they won’t really hassle you. And, you know, we can get into the weeds of like how that breaks down as protests become more extreme.

But, like, there’s protocols. ICE does not have that. They don’t really care. They will scream at you. They’ll yell at you. They’ll kind of break kayfabe. They are also filming you. They are, like, very intent on filming you with their cell phones. And with telescopic lenses, that they have guys parked behind them in cars, filming through the window.

Warzel: And that feels very different, right?

Broderick: I’ve never seen that. I’ve never seen that.

Warzel: That’s not something I’ve … even going back to Renee Good, the idea that there was an ICE agent that was filming while involved in this, you know, life-or-death—supposedly for him—situation, right? You’re claiming that, but at the same time you’re using your phone to document this. That feels very unique. That feels like a very different form of, you know, enforcement tactics.

Broderick: Yeah, I’ve never seen it. I’ve never had a law-enforcement agent pull up their assumedly personal smartphone and film me. Like, I’ve never seen that. And I mean, obviously, like there are agencies that do surveillance on protest movements, and it happens. But to have them just, like, have a gun in one hand and a phone in the other blew my mind. And I just have to wonder, Where is that content going? Where are those photos and videos going?

Warzel: Yeah. Anyway.

Broderick: Yeah, And so, like the fact that these guys are just taking photos of people and either uploading them to some kind of database or sharing them with each other, like, my mind sort of goes to: Okay, then what? So these guys, let’s say they have dozens of photos and videos of random people in Minneapolis on their phones. Like, are they sending them to each other? Being like, Keep an eye out for this person, and like beat their ass if you see them? I don’t know. We will eventually, at some kind of trial, perhaps find out what these guys are doing on back channel. But yeah. It sort of adds to the idea that these guys are like, I don’t know, content creators first and a Gestapo second. Or something. It’s very surreal, very dystopian.

Warzel: Yeah, and the nonprofessionalization of all of it, right? There is a piece, I believe it was last week, could have been the week before, where a reporter, writing for Slate, applied to work for ICE. Had a military background, but certainly was like somebody who had been hypercritical of the Trump administration and immigration policy, enforcement policies, and ICE in general. And still got hired. The idea of being, like, the threshold is so low. Did it add to the anxiety knowing that you’re dealing with a sort of improvised force? Not only that the guys are out there filming—it seems like they wanna be creating some content—but also just this idea that, again, the standards of training might be totally different. Did that add to the sense of unease, in terms of the protesters and the people who are around?

Broderick: Yeah. I mean, you can’t really predict what they’re going to do. I remember on the Saturday we were there, there’s this massive protest in Minneapolis. Thousands, 5,000 people. Many of them immigrants. Like, many of them with immigrant-rights groups and stuff. And, you know, we’re going through these little side streets in Minneapolis. And I just kept thinking, like, What is stopping Trump from saying on Truth Social, “Hey, get them”?

And Greg Bovino and everybody, like, cordoning off two sides of the street and just kettling everybody? You know, that can happen. Like, the sort of general unease of the whole thing is that you’re not dealing with an accountable, a rational, an identifiable law-enforcement group. You’re dealing with guys in masks that are filming you that don’t really have any kind of protocol. And don’t really seem to care about anything other than quotas.

I read that they’re supposed to be getting, like, 3,000 arrests a day. And the other thing is like: When they do detain you, in a normal situation, a reporter gets apprehended at a protest. You might get thrown in jail for like a few hours; maybe the weekend. You might miss filing your story. And then, you go home. With the ICE detention facilities … like, they might just put you somewhere.

And so, if you’re a reporter, and you’re trying to cover this, they’ve already made filming their activities a possible crime. According to what is NPSM-7. If you film their activity—

Warzel: Yes.

Broderick: —they can charge you with terrorism. They can charge you with obstruction.

And there’s really no oversight for what they’re doing. So the risks are just a lot higher than any sort of protest movement I’ve ever seen. Yeah.

Warzel: And I believe, what is it? It’s an NSPM-7, right? National Security Presidential Memorandum 7.

Broderick: NSPM-7, yeah.

Warzel: Is basically an executive order that is meant to dismantle left-wing terrorism and basically allowing the government to qualify people as “domestic terrorists” or “domestic terrorist organizations,” which allows for different standard of prosecution. And yeah, so that’s adding to all that confusion and chaos. So you saw this. You wrote, “We are all content for ICE.” It’s very clear that the Department of Homeland Security has basically transformed immigration arrests into this visual propaganda online. It’s very clear that there is a strategy here. There is a lot of pressure from the administration to have ICE really active in terms of a media campaign. What purpose do you think it is serving them to do that?

Broderick: I think everyone is trying to answer this question. And this might be an unfulfilling answer, but I think there’s a couple things happening simultaneously. I think, one, I think the Trump administration is full of genuinely xenophobic ideologues that want blood-and-soil nationalism. And they love this stuff. I think that Trump is a creature of the media, and he sort of understands that everything has to have a media component to it. And we’ve seen that … like, I don’t think that he’s playing four-dimensional chess. But I think he understands that everything he does has to have some kind of news cycle attached to feel like it matters for him.

Warzel: Well, I’ll just say: On January 20, which is Tuesday of this week, Donald Trump posts on Truth Social, like, We need more photos of people who we’re arresting in Minneapolis. We need more documentation of just how bad they are. Like it’s very clear that while he’s not playing four-dimensional chess that we know of, he is, as you said, just hyper-aware—

Broderick: Yes.

Warzel: —of the idea that this needs to be fed. People need to have this raw meat of “Our nation is under siege” in order to continue to support and to justify this.

Broderick: Right.

Warzel: Yeah, anyway.

Broderick: And I think the last part of this is: I think it is safe to assume that the Trump administration is inside of their own filter bubble. I think this is happening across culture en mass. And I think, based on the reports we have seen coming out of sort of the inner circle—you know, if you want to believe them—they were surprised that people were pissed about this. And I don’t think Trump is actually particularly online. I’ve never thought that. I’m like, I don’t think he knows what 4chan is—but I do think that he has surrounded himself with podcasters and posters. And I think that those people are super tapped into X.

And so, we haven’t actually talked about this dimension of what’s happening in Minneapolis yet, but I think it’s important context. So ICE has been in the state for months. All of this ratchets up after the YouTube documentary by the right-wing influencer Nick Shirley. Nick Shirley’s documentary alleges fraud at day cares in Minnesota. All of it had been reported before. It was even being investigated by the FBI already. Like, we’ve known about this. But the right-wingers who had never heard of this—because they don’t read real newspapers, and don’t have accurate information pipelines—were incensed.

So that, to me, points in the direction of: These people genuinely do not know things. And you can say it’s by design. You can say it’s because they’re all stupid. You can say it’s because they’re addicted to the internet. Could be a combination of the three. But that does inform their behavior. And we’ve seen this all year, all of last year. That they are—the administration is doing things because they see them online.

Warzel: Right. And also, think, too: There’s the other side of this. And you wrote about this. I can’t believe this was also in January, when the United States invaded Venezuela. But, you know, the idea of a content-first administration. But something you wrote—I’m going to quote you to yourself here. Which is always fun, I know. You said, “Politics—and political violence—is now something performed, first and foremost, for an online audience. It almost doesn’t matter what happens IRL if it makes noise online.”

And I think that, you know, that it’s not just what you’re saying—which is that there is this filter bubble. There’s this idea that this is acceptable, right? Like, ltheir whatever, Overton window or whatever you want to call it. Like: This is fine. We can do this. People won’t be mad if we act in this particular way. But there’s also the idea of that imagined audience, that maybe someone sees on X or some other place or whatever. But it’s this idea of almost one-upsmanship. It’s like, you do this video of what’s happening in Minneapolis, supposedly with day cares and Somalian refugees. And we’re going to basically perform fan service by sending a paramilitary force into that town. It seems like that level of the performance is really, really important here.

Broderick: Yeah. So once again—for people who are not like mainlining this stuff all day—and they’re sort of thinking like, okay, Trump too. It’s a little more in your face. It’s got like a fresh new attitude, but it’s like—basically it’s the same idea. And there’s, like, a core loop has changed. Trump: One, he wakes up in the morning; he watches Fox & Friends. He performs the day. He then finds out the next morning how Fox & Friends has, like, digested what he’s done. And he just keeps going. Right. So everything’s kind of performed for this TV channel that is then sort of synthesizing what he’s doing and then influencing what he’s doing.

So the difference, though, between that loop and this one is that the internet is inherently a two-way street. So it’s not just what was sort of downstream in the first administration—like, the internet lights up because Trump does something, because Trump saw it on TV. And then TV lights up, and then TV—like, the role of TV in that equation kind of organizes things in a way. Was like a rhythm, too; there’s a much more sort of reliable rhythm to it.

This is way more chaotic. Because, like, Nick Shirley: He’s making a video based off of what he’s already seeing on the internet. It then goes back into the internet, which then influences what’s happening in reality. Which then influences what’s happening on the internet.

And I was sort of trying to figure out: Okay, when did this this new loop start in earnest? And I think I have it, which is the playbook. The test drive for all of this was Springfield, Ohio, and the conspiracy theory about Haitian immigrants eating cats and dogs in the park.

That whole thing, though, is a perfect illustration of what is now happening everywhere all at once. And it’s happened, and I’ve even seen examples of it happening in Venezuela, happening in Greenland. Like, it’s this roving, kind of, internet-content machine that just sort of lands where you live and then turns everything that’s happening to you into this completely inexplicable content cycle. That, you know, for people on the ground, makes no sense—because it’s not really meant for them. And it comes with conspiracy theories and viral videos and racist memes and AI imagery and paramilitary violence. Like, it’s all kind of part of the same thing.

Warzel: It’s really interesting to think of it as almost like a storm system, that develops outside and just comes to your town. I have had trouble trying to get a sense of who this is helping; who this is hurting. Right? ’Cause on one hand, you have all of this documented evidence of what is essentially a paramilitary force drawing guns, you know, in public places on people. Deploying tear gas and pepper balls and all kinds of, you know, chemical sprays on citizens. Arresting people on whims, intimidating people, mocking them. And there’s obviously, of course, the video of an ICE agent shooting a woman in broad daylight.

And that all adds up, I think, in the eyes of people watching online or wherever. That is doing something right to people, and how they view the country. Their country. And then at the same time, these protests can also—as we’re noting—give the administration a little bit of what it wants, right? It gives them content in order to depict these cities as war zones.

And do you get a sense of if this is, like, serving ICE’s propaganda needs effectively right now? Or if this is in some ways just information that is radicalizing people? To get them to, you know, wake up to the political reality in the United States. Where do you see that balance? Or like, where that’s coming out at the moment?

Broderick: That’s like the million-dollar question, I think. I mean—

Warzel: Right. That’s all we ask here on Galaxy Brain, is the million-dollar questions.

Broderick: Thank you for asking me the most complicated question of our time. I think there’s a couple of ways to think about it. And they are—this is always my cop-out, but I do think in this case, if American monoculture ever did truly exist, we like to imagine it did, you know, pre-Facebook. But maybe it didn’t. Maybe, like, the TV and movies made it feel like it existed, and we could all sort of believe in that. But let’s assume things are different. I think there are vastly different realities happening simultaneously in America. So there are people who are just not going outside, and they are consuming all of this online. And they are being radicalized either for or against it. And that’s, like, one camp.

And then there are the people that it’s happening to directly. The ones I talked to are just the most average Americans you could possibly imagine. And they’re like, This is insanity. And do I have to, like, go to the federal building and blow whistles every day because these people won’t leave me alone? And I’ve met those people, and they are just like the most normal people you can imagine. And they are incensed. They’re furious.

And then I think that there are a lot of Americans who just really do not believe that this could happen to them. And those realities, like, don’t really line up anymore. Because we’re not all looking at the same feed of information. We’re not all looking at the same screen. And it adds to the chaos. It adds to the unpredictability of all this. Because, you know, there are a lot of, like, non-white immigrant Groypers that sit online all day talking about how they love Nick Fuentes and think the Holocaust didn’t happen. What happens when ICE breaks down one of their doors? Right? Like, there are a lot of these keyboard-warrior types who do not imagine this could ever happen to their town. And if it does happen in their town, it’s going to happen to the people who deserve it in their town. And yet, time and time again, for the last year, we’ve seen stories come out, being like: I didn’t think they’d take the good immigrant in my town, that I liked. You know?

And so there are—I don’t think the average American really is prepared for the severity of what’s happened. Like, of when it happens to them. And it is in, I think, the Trump administration’s best interest to flood the zone with images of this stuff. Because it does make it feel abstract. The average person watches and cares until it no longer looks like it could happen to you. And I think that does serve Trump’s interests. If Minneapolis looks like a completely unrecognizable war zone, that’s great. It just means that the person watching goes, Well, that doesn’t look like my backyard. So I should be fine.

Warzel: Mm-hmm. Right. And I was just really struck in your guys’ reporting for Panic World, which came out in a video-podcast form as well—which, people should go watch that. You know, some of the people you interviewed were like—and this has been documented elsewhere as well—the most Minnesota Nice. You know, like just sort of, Yeah, you know, I just came from my shift at school. Or whatever. It’s like when you see that and you feel that there is this way of just being. Like—I think it brings the sort of, it’s a great contrasted image with the paramilitary force. It’s like, anyone who’s drawing guns on this person? Like, we’ve totally lost the plot. It’s not that it’s justified when it happens to people who don’t, you know, maybe look like you. But just this idea of … it’s a strong visual image for people who are watching at home, is what I mean.

Broderick: I think it’s also a self-perpetuating machine. Because—forget who made this point. Maybe it was Wired. I think it was Wired last week, this week. They’re all blending together. But they were basically like: There’s no reason for the Proud Boys to exist anymore, because ICE exists. And so if you’re running … I mean, Trumpism doesn’t really have an ideological center, but if you had to try to define it, you’d say, Okay, it’s like grievance-based. It’s like the Trump supporters hate other people for various reasons, and we’re gonna make a big tent where all your different grievances kind of live in semi-harmony together. And we can hurt others.

And then if you open up a paramilitary force, that requires what? 4Forty-seven days of training to join, and they’re not even gonna like check if you’re a Slate reporter or not. Like, you can just go and hurt other people. And so, in a sense, almost, it almost makes logical sense that this would be the next step for Trumpism. Because you can’t sustain that, like, othering of Americans long-term, without some way to get people to sign up and do it. So it’s almost like we have to create this paramilitary force, and we have to start paying people to do this. Because if we don’t, that energy could dissipate. Or they might just find out that maybe we’re not also different after all.

Warzel: This was something that I was thinking about in different way. And it is a bit of a tangent. But I’ve—as you have been writing about, you know, MAGA influencers, and stuff like screeching online about “civil war” since like 2017 or whatever, right? Like, people who are just like, This is going to lead to some kind of, you know, massive crack-up type thing. T

Then so many people that I’ve talked to who are actually, you know, experts in this type of stuff and in conflicts are like: “You know, part of the reason why terms like civil war are like so unhelpful is because it’s incredibly difficult to imagine in certain places, especially a country as big as the United States, giving structure to a conflict like that.” This idea that’s like, so much of it would just be, you know, weird infighting. Or, you know, acts of almost seemingly random terrorism or whatnot. Right? And the thing that I have found so interesting and scary about the way that the Trump administration is not only using ICE, but the way that they are marketing it, right? This idea of all of this propaganda that’s very clearly aimed at white nationalists. “Defend the homeland” type of stuff.

The reason why I find that so bracing in the moment is that it feels like—and this is sort of, I think, what you’re saying—that it’s giving structure to a conflict, right? It is just sort of like a repository for, if you feel this way, like, about your country being under attack or invasion. Or you’ve been radicalized by some of these platforms to the point where, you know, posting just isn’t doing it for you anymore? Here’s a place to go, right? Sign up. And it becomes less of like—you can see, you know, in a sort of speculative way, this becoming a repository for a very specific type of person. And a force that actually does resemble what some of these militia-like organizations were, right? Except in this case, it has government funding. And, you know, according to both J. D. Vance and Stephen Miller, absolute immunity for your actions. And that feels like it is a completely different, or like a turn of the screw on this concern about infighting in this country.

Broderick: Yeah, no—I think that’s exactly right. If we take the reports at face value that morale is very bad inside of ICE, I do wonder how they deal with that. You know, like you, I’m always sort of saying, like, What’s next? Is this working? Is this not working? And if we say that, okay, those reports are correct. Like ICE agents are miserable. They join ICE. They’re all revved up on white-nationalist Facebook content. And then they hit the streets, and everyone’s like, “Get the fuck out of my city.” Like, “I hate you.”

I mean, I heard the heckling in Minneapolis. And they found out a bunch of their names, and they just kept chanting, So-and-so, quit your job; so-and-so, quit your job. And these people are becoming pariahs. So that, to me, is like, your filter bubble has lied to you. You’ve joined this federal agency for student-loan forgiveness or whatever it is. And now you’re in the middle of Minnesota in the middle of January, and everyone’s screaming that they hate you and spitting at you and stuff. You might quit. And that’s, like, a hopeful version.

And then there’s the scarier version. Which is like: What does the Trump administration do with that? Because we are dealing with like lots and lots of people who are getting revved up on stuff they’re seeing online, who maybe would have joined a militia and LARPed Confederate soldiers in the backyard for the next five years. But now they’re out with guns, and they’re like trying to struggle with the cognitive dissonance of The world online and the world in real life are not the same. You know, what does that do to a paramilitary force like ICE? Like, what is the next step? And I assume you’re right. Which is like: They just start dehumanizing us further and further with internet content.

Warzel: Yeah, I mean, as you’re giving the hopeful version, I’m like: Well, this just absolutely totally rhymes with everything that we have covered over the last, you know, whatever decade on the internet. Where it’s like: Yeah, there is this version in which everyone’s like, Okay, that was a fever dream. Like, whoa, like the cognitive dissonance hits, and you say, Okay, yeah, man, I was just totally wrong. Like, this is awful. This is a terrible way to live. Or what tends to happen online—and again, doesn’t always happen in the real world because there is more friction there—is this idea of doubling down, right? Well, why declare being wrong, when I could just simply make up a reality? Or make up something? Right. Exactly.

I want to ask you to try to put some of this into some context. And I’m going to do the wonderful thing where I quote you again. But I went back, and I read a story. We both used to work at BuzzFeed News. You wrote this back in late 2018. I think it was after [Jair] Bolsonaro won in Brazil. And I believe that you were there on the ground. I’m going to read this, which is you said, quote: “I’ve followed that dark revolution of internet culture ever since. I’ve had the privilege—or deeply strange curse—to chase the growth of global political warfare around the world. In the last four years, I’ve been to 22 countries, six continents, and been on the ground for close to a dozen referendums and elections. I was in London for the U.K.’s nervous breakdown over Brexit, in Barcelona for Catalonia’s failed attempts at a secession from Spain, in Sweden as neo-Nazis tried to march on the country’s largest book fair. And now, I’m in Brazil. But this era of being surprised at what the internet can and will do to us is ending. The damage is done. I’m trying to come to terms with the fact that I’ll probably spend the rest of my career covering the consequences.”

I have a few questions here. And the first is: Do you still feel like you can draw a straight line between all this? That was there, and all that has come after—from COVID to George Floyd to January 6 to Trump 2 to Minneapolis now. Like, did you feel like there’s a straight line here? Did it break off and shift in different directions?

Broderick: With the benefit of hindsight, I think the attitude in 2018 to say this is all because of internet platforms is a little simplistic. I think it’s a little ahistorical.

Looking at the whole picture—or at least the picture up to now—it seems clear that the sort of post–Cold War geopolitical order, this kind of neoliberal end-of-history idea, was deeply alienating and frustrating for people. The concept that we are all kind of done, and we’re just going to get incrementally better in progressive ways. Maybe we’ll have, like, a Republican come in and kind of calm things down, and then we’ll go back and forth. And that idea was extremely frustrating to people. And when social media appeared, it allowed people to communicate without arbiters for the first time.

So you start to see things like the Ron Paul presidential campaign in 2008, which I’ve gone back to several times because things are such a fascinating sort of prototype of everything since. Occupy Wall Street, Arab Spring, the very first Black Lives Matter stuff. And what I think you and I, and other people doing this work, we’re not really totally getting—because of the nature of the way we cover it. Which is not a problem. It’s just that no one can see the whole picture.

Is that like—the technology didn’t really create pathways that weren’t there. What it did was allow us to see them. And so, it’s why I said earlier in the episode that we don’t know if monoculture was as monolithic as we assume it was pre-internet. Could just be that we didn’t know. And so I think there is a straight line from, let’s say, the launch of message boards in the ’90s to now, and Facebook, and everything else along the way.

But it’s not like Facebook conjured up some kind of political environment that wasn’t there. It’s that it gave people like [Rodrigo] Duterte, like [Narendra] Modi, like Bolsonaro, like Trump, like Marine Le Pen—gotta catch them all. All these people, it gave them the ability to speak to an audience that was already alienated and already angry and already bored. And that dovetailed perfectly with the way internet technology has developed in that same timeframe.

So, you know, now we’re at a point where they are essentially the same thing. What is good for the internet is good for your populist far-right movement. And yeah, I think that will sound right. Five more years from now? I think, yeah, I don’t know.

Warzel: Ryan, I thank you for your reporting on this, for being in the pain, the emotional pain cave, the internet brain-damage Thunderdome with me for all these years. And thanks. Thanks for all your insights on this.

Broderick: Hey, I’ll see you in the gulag.

Warzel: Ryan, thanks for coming on.

Broderick: Thank you.

Warzel: That’s it for us. Thank you again to my guest, Ryan Broderick. If you liked what you saw here today, new episodes of Galaxy Brain drop every Friday. And if you want to support this work, the work of myself and all of my colleagues at The Atlantic, you can do so and support the publication by subscribing at TheAtlantic.com/Listener. That’s TheAtlantic.com/Listener. Thanks so much, and I’ll see you on the internet.

The post ICE Is Turning Real Conflict Into Viral Content appeared first on The Atlantic.