Most talk about art focuses on how it sits in the world after it’s framed or put on a plinth — what art means, how beautiful or how insightful it is, and so on. But I’ve noticed a new trend: More and more exhibitions and books about art are drilling down into practicalities — into the aspects of creativity encountered by anyone who reaches for a pencil, a camera or a brush.

They’re responding, I think, to a widely felt phenomenon. As our experience of the world is colonized by the opaque and frictionless operations of all things digital, young and old alike are turning their hands to ceramics, watercolors, knitting and drawing as they try to escape the clutches of their phones.

This welcome development is affecting art history and museum culture, too. Twenty years ago, Anne Baldessari, a former director of Paris’s Musée Picasso, noticed that commentators on art showed little interest in “the genesis of art, focusing instead on the outward manifestation of the masterpiece.” It was time, she thought, for people to recognize that making art is a messy business. “We would do well to go directly to the source,” she wrote, “in order to get at the mystery of the working process.”

You can get information of this technical kind from all sorts of books about art-making. But unless you’re in the studio and need to know something specific, tomes such as W.G. Constable’s “The Painter’s Craft: Practices, Techniques and Materials” (1954) and Ralph Mayer’s “The Artist’s Handbook of Materials and Techniques” (1940) can be a little dry.

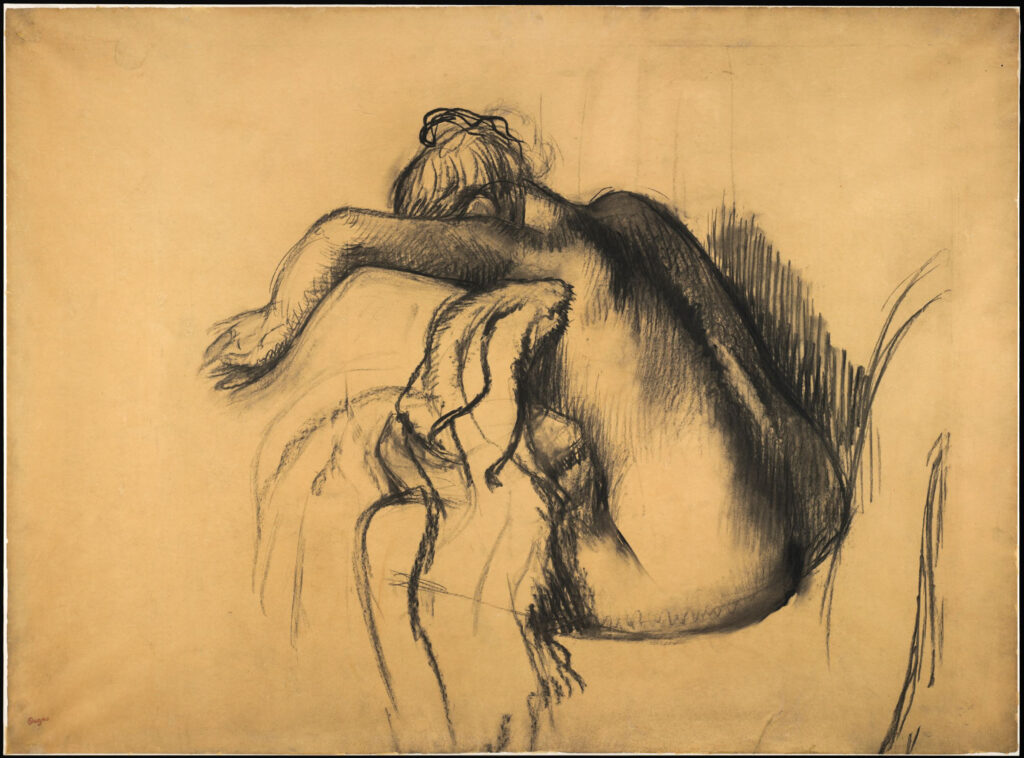

Fortunately, there are other ways into the mysteries of making art. Harvard Art Museums staged a show over the winter titled “Sketch, Shade, Smudge: Drawing From Gray to Black.” It included astonishing feats of drawing by Georges Seurat, Adolph Menzel, John Singer Sargent, J.-A.-D. Ingres and Edgar Degas.

But as you shuffled from work to work, you were encouraged to think not of genius or cultural context or “significance” but of charcoal, chalk, crayon and graphite. You were invited, that is, to get to grips with what these basic materials actually are, how they interact with the surfaces to which artists apply them and all the different ways they have been used. Physically.

Charcoal, if you’re wondering, is made by charring wood in an airtight container or oven. Its vegetal origins can be seen under a microscope: It has a “porous structure and elongated particles, which resemble splinters,” the wall text informed us; it has a brown or gray tint, making it hard to achieve deep blacks; and it leaves “an ashy trail as the particles settle into the slight valleys in the paper.” It’s good for smudging.

Chalk and graphite, on the other hand, are mineral. Chalk began to be quarried from deposits of shale or schist in the 1500s. In the 19th century, people found ways to fabricate it so it was eventually supplanted by “well-meaning imposters” such as conté crayon and pastel.

Crayons are just colored pigments in a wax binder. They can be designed for use either in lithography or in straight drawing, and they come in a variety of hardnesses. “Crayon frequently appears clumpy,” said a helpful wall label, “especially where it stops and starts, and it often skims along the high points of a textured paper.”

Plainspoken wall labels like these are a nice change from jargon-filled curatorial texts and pretentious artist statements. They make you want to go home, pick up some charcoal and push it across a piece of paper.

A display of South Asian paintings at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts takes a similar approach. It refrains from trying to interpret these ravishing artworks, drilling down instead on what is most distinctive about them: their colors, the way each artist uses a particular hue and how they got their hands on it.

Indian artists, for instance, generally used two kinds of yellow. The first, and oldest, was orpiment, made from a mineral of the same name — a highly toxic sulfide of arsenic, which had the compensating advantage of protecting the artwork from insects.

The second, aptly named Indian yellow, came into use in the 1580s and was made from the crystallized urine of cows fed exclusively on mango leaves.

Are you kidding me?! Is there no limit to human ingenuity when it comes to creating the conditions, the potential, for visual beauty? Who knew?

These two shows were put together by conservators and curators and benefited from their insights. But for all their technical knowledge, museum professionals don’t see creativity in quite the same terms as artists do.

In her marvelous book “Art Work,” the acclaimed photographer Sally Mann (author of the memoir “Hold Still”) delights in puncturing the piety around art-making. “When I use the word ‘art’ to refer to the stuff I make,” she writes in the prologue, “there are quotation marks around it in my mind.”

It’s hard to think of a photographer who has more forcefully made the case for her medium’s artistic potential, but Mann has never been precious about it. “Being an artist is not such a big deal,” she notes. It’s just “a job, a profession not unlike being an insurance adjuster or a sportscaster.”

Her book arrives as a tonic. It is “about how to get s— done.”

That same expletive recurs in a related context on Page 2, in a hilarious anecdote (she has told it before, and why not?) about Cy Twombly, her friend and neighbor in Lexington, Virginia. Mann was with him at his studio when some fastidious art handlers finished their packing and the “van door was shut on his paintings, destined for some billionaire’s collection,” as Mann puts it.

“Glad to get that s— out of here,” said Twombly, as they watched the truck finally drive away. Twombly then went to relax in the sun on “the benches at the nearby Walmart.”

If Mann’s book is about the creative process, it’s generous in the scope it bestows on that term. It’s not about chemistry, equipment or technique (although you learn fascinating details about all this along the way). It’s about making art in the context of life — life with all its vicissitudes, tribulations and competing demands.

Mann lives on a farm. She is a mother and grandmother and wife. Her advice is presented in the most practical, down-to-earth and personable manner. It’s lent disarming authenticity by the inclusion of journal entries, fragments of letters, old contact sheets, Google search page results and shaggy anecdotes with tenuous life lessons attached.

Mann discusses the dangers of early “promise” and distractions; the psychic strain — and sometime usefulness — of rejection; the role of luck; the need to work hard; and the value of saying “Yes,” even when you suspect you are getting in over your head.

Creativity is not, in the end, about camera equipment, this book reminds us, or about whether you choose to draw on wove or laid paper. Those questions are important. But art draws on something deeper and more elusive.

“Within each of us,” writes Mann, “is a precisely tuned and personalized sphere of receptivity — think of it as a magnetic field — whose unique settings have been determined by our own life experiences.”

Many things pass through this field, she explains. Some of them “fluoresce” (other people might not even notice them) and when they do we scrutinize them, over and over; “they remain elusive until, unbidden and alien, they emerge in the art we make, revealing the story that we did not realize we had been telling.”

So what are you waiting for? “Pick up your pencil, your camera, your paintbrush,” implores Mann.

Relish the feel of it, the sounds, the rhythm as you work. See what happens. Are you making “art”? Are you being “creative”? No one cares right now. You’re making something.

The post How art gets made, and why it might involve cow urine appeared first on Washington Post.