On Tuesday, the full, 17-judge U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit heard consolidated oral arguments in a crucial case that is all but guaranteed to make it to the Supreme Court. The predictable controversy surrounding the litigation, which involves similar but distinct mandatory Ten Commandments display laws arising out of Texas and Louisiana, is revealing as to just how far America has fallen from its founders’ vision.

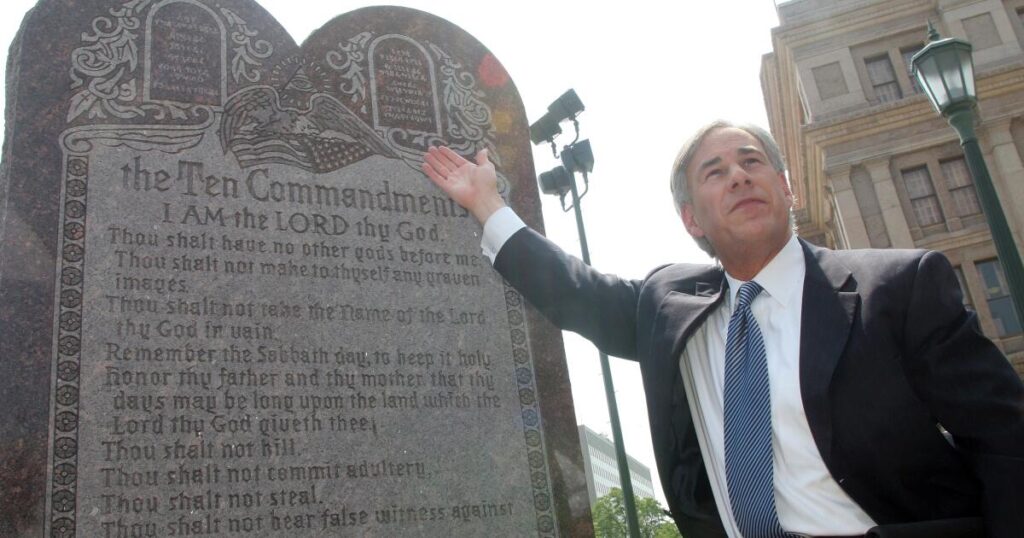

In 2024, Louisiana Gov. Jeff Landry signed into law a bill requiring that the Ten Commandments be displayed in every public school classroom — from kindergarten through the university level — throughout the state. As Landry explained at the time, “If you want to respect the rule of law, you gotta start from the original lawgiver, which was Moses.” Last year, the Lone Star State followed by passing a nearly identical statute. Texas Gov. Greg Abbott, who as Texas attorney general in 2005 successfully defended a Ten Commandments monument on the Texas State Capitol grounds before the Supreme Court, echoed Landry in signing Texas’s bill: “Faith and freedom are the foundation of our nation.”

Aggrieved liberals and secularists immediately filed 1st Amendment lawsuits, and district court judges promptly enjoined enforcement in both states. The question now pending before the New Orleans-based 5th Circuit, where I once served as a law clerk, is whether the Ten Commandments laws may once again be enforced so that the Decalogue can hang on all classroom walls throughout Texas and Louisiana.

Let’s start with first principles. The first clause of the 1st Amendment, widely known as the Establishment Clause, reads, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.” The two relevant words in the Establishment Clause are “Congress” and “establishment.”

The word “Congress” is relevant because the Establishment Clause was unambiguously intended only to apply to Congress — and, by extension, the federal government at large. As Justice Clarence Thomas and others have persuasively argued, the original understanding of the clause was to prohibit Congress from establishing a national religion so that the states may do so themselves — consistent, of course, with prevailing free exercise protections and the No Religious Test Clause of Article VI of the Constitution. From the founders’ perspective, the Establishment Clause was a necessary federalism provision for a fledgling, religiously pluralistic republic.

The word “establishment” is relevant because it can only mean what the founders meant: a literal national established church, such as the Church of England. Generations of Americans have been taught that the 1st Amendment secures the “separation of church and state,” but that pernicious phrase is nowhere to be found in the amendment. Instead, the notion of a “wall of separation between Church & State” has its origins in a pithy 1802 letter Thomas Jefferson sent to the Danbury Baptist Assn. in Connecticut. As Justice William Rehnquist explained in his dissent in Wallace vs. Jaffree (1985):

Thomas Jefferson was in France when the Bill of Rights was passed by Congress and ratified by the States. His letter to the Danbury Baptist Assn. was a short note of courtesy, written 14 years after the Amendments were passed by Congress. He would seem to any detached observer as a less than ideal source of contemporary history as to the meaning of the Religion Clauses of the First Amendment.

In reality, Jefferson’s “separation” language didn’t take hold until a terrible 1947 Supreme Court decision called Everson vs. Board of Education, which for the first time undermined both “Congress” and “establishment” by adopting Jefferson’s insidious language and then “incorporating” it to the states as well. The result has been nearly eight decades of destructive constitutional inversion and a prolonged moral assault on America’s biblical inheritance throughout our public squares. In a law review article published last summer, my co-authors and I called for the Supreme Court to overturn Everson and end our failed national experiment in “separationism.”

None of this is even necessary to decide the 5th Circuit case. The United States was founded on ecumenical biblical principles, and the Ten Commandments — the wellspring of so much of Western morality — embody that ecumenicism. Introduced to the world by Judaism and spread throughout the world by Christianity, the Ten Commandments are the shared inheritance of Jews and Christians of all stripes — Orthodox, Protestant and Catholic. The Supreme Court itself famously features a frieze of Moses carrying the Ten Commandments tablets. It would be the height of hypocrisy for the court to deny to Texas and Louisiana the ability to do that which it does itself. Sectarian public displays perhaps raise other concerns, but the Ten Commandments simply do not.

On the very same day in 2005 that Abbott and then-Texas Solicitor General Ted Cruz successfully defended the Texas State Capitol grounds Ten Commandments monument, the court decided a very similar case out of Kentucky that inexplicably went the other way. For decades, the court has made a muddled hash of the 1st Amendment’s Establishment Clause. It’s been trending in the right direction in recent years, and the justices should eventually have an opportunity here for a landmark, clarifying ruling. But for now, the 5th Circuit must do the right thing and side with Texas and Louisiana.

Josh Hammer’s latest book is “Israel and Civilization: The Fate of the Jewish Nation and the Destiny of the West.” This article was produced in collaboration with Creators Syndicate. X: @josh_hammer

The post The 1st Amendment was never meant to separate church and state appeared first on Los Angeles Times.