Big Tech is taking on record levels of debt, marking a new chapter in the artificial intelligence boom as names like Oracle, Alphabet and Meta pour big money into massive data centers and the energy systems needed to run them.

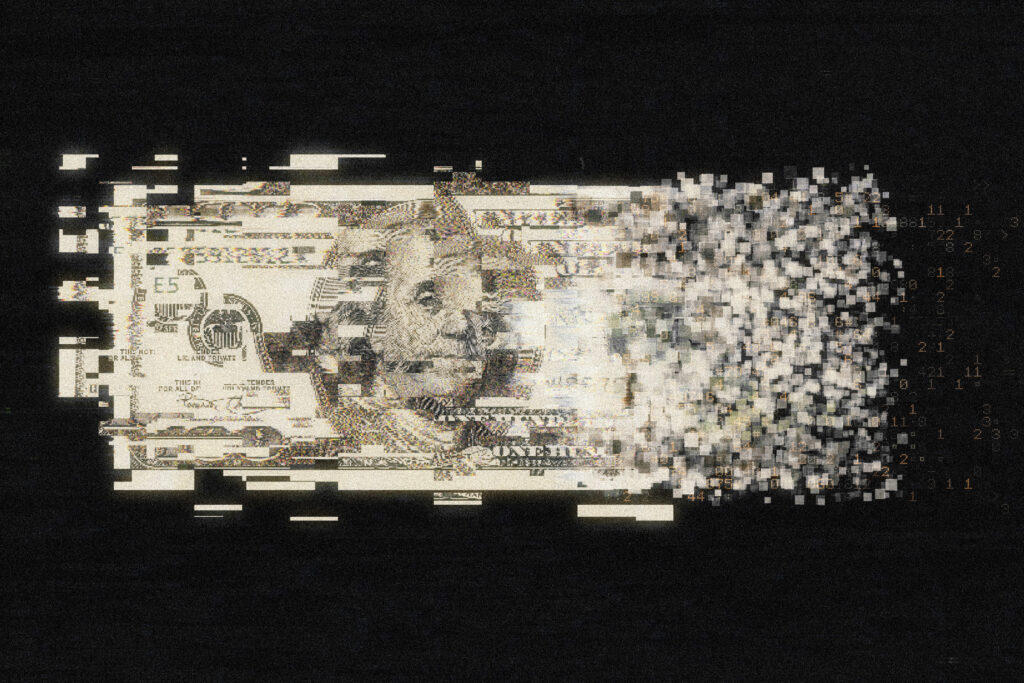

Technology companies issued a record $108.7 billion in corporate bonds in the last three months of 2025, according to data from Moody’s Analytics. That’s the largest total for any quarter and roughly double that of the previous three months. And the trend is extending into 2026: Some $15.5 billion in bonds were issued in the first two weeks alone.

For now, investors are assuaged by the eye-popping cash flow numbers from major tech companies. In the past 20 years, Big Tech companies including Google, Microsoft, Meta, Amazon and Apple have built what are arguably the most profitable business models in history. In the third quarter, Google brought in just over $100 billion, with a margin of over 30 percent. All five are trillion-dollar companies, as are such AI darlings as Nvidia, Broadcom and TSMC.

But some economists and business analysts say the massive new bonds are spreading risk throughout the economy, with hundreds of billions being spent on a technology whose profit-making potential is not yet clear.

“It’s a lot of debt, and a lot of it all of a sudden,” said Mark Zandi, chief economist for Moody’s. When companies are funding risky ventures with debt “it does put the broader financial system at risk. If the financial system is at risk, then the broader economy is.”

A bond is a form of debt that companies or governments can use to raise large sums of money, typically from investment banks or private-equity firms, to be paid back with interest. They historically have been used to fund major infrastructure projects such as power plants, natural gas drilling operations or offshore wind farms — projects with large up-front costs that are expected to generate revenue for many years. Once issued, a bond can be bought, sold or packaged into other debt products, which can end up in the portfolios of unrelated investments such as pension funds.

Automakers, utilities and other mainstays of heavy industry have historically been the biggest issuers of corporate bonds, Moody’s data shows. Analysts note that in past technology build-outs, such as the rise and rapid investment in internet-based companies in the 1990s, companies didn’t have to spend nearly as much on infrastructure.

That has now changed, given the unprecedented energy demands of running and training AI algorithms. While tech companies took on more debt, adjusting for inflation, in 2021 than in 2025 — with a total of $296.6 billion in 2024 dollars issued that year — interest rates were significantly lower at the time. That made financing debt cheaper.

“The technology industry has gone from being an also-ran in terms of corporate debt, to becoming the largest player of investment-grade corporate debt, out of nowhere, compared to two years ago,” said venture capitalist Paul Kedrosky.

Because training and running AI algorithms takes up much more computing power and energy than previous forms of technology, staying ahead in the AI race costs billions. Google, Microsoft, Amazon and Meta indicated in company announcements that they planned to collectively spend well over $300 billion on AI data centers in 2025 alone.

If they continue to spend at that rate, they may have to take on even more debt.

“If these companies are so profitable, why are they using debt?” Kedrosky said. “It gives you a sense of the scale of what’s going on.”

Amazon spokeswoman Amy Diaz said the proceeds from Amazon’s bond issuance in November is being used to support business investments, capital expenditures and repayment of earlier debt, adding that the company regularly evaluates its operating plan to make financing decisions. (Amazon founder Jeff Bezos owns The Washington Post.)

Representatives from Alphabet, Meta and Oracle either declined to comment or did not answer questions. An Apple spokesman referred to the company’s SEC filing, which states that proceeds from the bond issuance would be used for “general corporate purposes” including stock buybacks and unspecified capital expenditure, among other uses.

Among large tech companies, Meta used the most debt to fund its data center build out in 2025, according to Moody’s. The social media company has invested deeply in AI in a race to become the leading AI assistant for companies and everyday people, putting it in a tight race with Microsoft, Apple and Alphabet.

Mark Mahaney, who has covered tech companies for more than two decades and is now managing director at the investment bank Evercore ISI, views the bonds as part of a strategy by tech firms to raise money without degrading their stock price. Bond offerings are a sign that management is “confident or cocky” about their future, as they’ve taken on debt that requires steady cash flow to pay down, Mahaney said.

Also loading up on debt is Oracle, which issued some $25.75 billion in bonds last year as it seeks to become the AI computing power provider of choice. In September it disclosed a $300 billion deal with OpenAI, prompting an immediate 36 percent spike in its stock price that briefly made founder Larry Ellison the richest man in the world. (The Post has a content partnership with OpenAI.)

But in the ensuing weeks investors became uncomfortable with Oracle’s debt. Citi analyst Daniel Sorid told CNBCin December that there was something “inherently uncomfortable” about the “enormous” amount of capital Oracle will require.

As of Thursday the stock had declined about 45 percent from its Sept. 10 peak. Bondholder Ohio Carpenters’ Pension Plan recently sued Oracle and several investment banks, alleging that Oracle failed to disclose how much debt it needs.

“The sheer scale of new debt issuance has forced investors to reassess whether the economics of relentless AI [spending] are truly sustainable,” said Thomas Urano, chief investment officer at Sage Advisory in Austin.

Urano added that many of the companies getting AI-driven investment are part of the infrastructure that enables today’s AI chatbots and other applications, which cannot be immediately monetized.

“This creates a paradox: The strategic case for AI is compelling, but the revenue model is still evolving,” Urano said.

At least one firm has raised the prospect of getting government support to build out more data centers. OpenAI’s chief financial officer, Sarah Frier, saidin November that it will require “innovation” on the finance side, with government providing a “backstop” or “guarantee.” Her comments triggered backlash from politicians and tech critics, who questioned whether taxpayers should take on some of these private companies’ risk. Frier and CEO Sam Altman both later clarified that they weren’t seeking federal guarantees for OpenAI data centers specifically, although Altman did say in a lengthy social media post that a government-funded “strategic national reserve of computing power” would make sense.

The Trump administration has gone all in on AI, pushing aside concerns within the MAGA movement and seeking to sweep away regulations that it says hamper innovation. But neighbors of the vast warehouses of computer chips that form the technology’s backbone — including in conservative states — have objected to how the facilities sap power from the grid, guzzle water to stay cool and secure tax breaks from local governments. Trump has recalibrated his approach, pushing tech companies to fund their own power.

“Historically when we’ve had major bubbles they’ve tended to be about real estate, or technology or government policy,” Kedrosky said. “This is the first bubble in history that combines all of these things.”

Gerrit De Vynck contributed to this report.

The post Big Tech is taking on more debt than ever to fund its AI aspirations appeared first on Washington Post.