The last Nazis on Greenland were captured in October 1944, when American soldiers raided a hidden German weather station on the island’s desolate west coast and took dozens of prisoners. Within a year, Germany would be defeated and World War II would be over.

But 80 years of both tension and cooperation between Denmark and the United States over Greenland was just beginning — culminating in President Trump’s current obsession with acquiring the Arctic island.

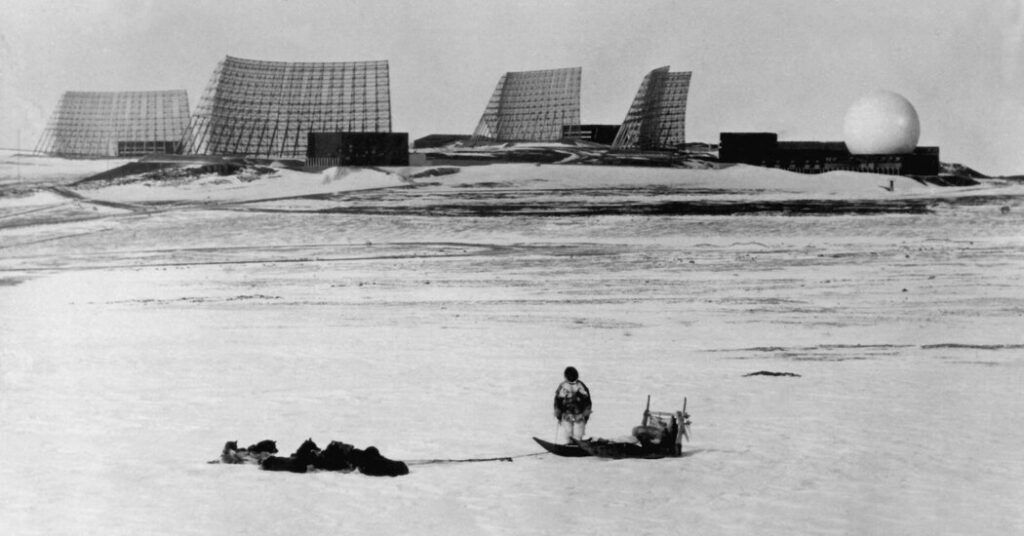

While the story begins with World War II, it was shaped by the Cold War that followed, in which the United States transformed barren Greenland into a major military asset, populating it with air bases, towering radar sites and even a never-completed underground bunker complex meant to house nuclear missiles.

It was all possible under an agreement with Denmark that granted the United States nearly unlimited military freedom on the island, one that remains in force today.

“We did it before, we can do it again,” said Daniel Fried, a former senior State Department official who worked on Soviet issues in the 1980s.

Whether Mr. Trump understands this history has been a mystery as European leaders try to convince him to drop his insistence on owning the island. Mr. Trump said on Wednesday that a “framework” for a deal had been reached, but the details remained murky.

In an era before military air power, before Mr. Trump was even born, American military planners gave Greenland little thought. But when Germany invaded and occupied Denmark in 1940, they realized that the island, then a Danish colony sparsely populated by mainly Inuit people, was vulnerable to Nazi control.

With airfields perilously close to America’s east coast, important mineral reserves and an ideal location to track weather that shaped battle conditions in Europe, Greenland’s defense was considered essential to the United States. It was an idea that would persist for decades before fading briefly after the Cold War and returning with a vengeance in the Trump era.

Denmark’s exiled king had welcomed the American force and approved a written agreement granting the broad military latitude on the island, as long as a threat existed, without giving up any Danish sovereignty. With Germany vanquished and the war over, however, his country was ready to bid the Americans farewell. “Danish public opinion was expecting a return to full control of Greenland,” explained a study of the matter by the Danish Institute of Public Affairs.

Washington had other ideas. The advent of long-range bombers had created a new sense of vulnerability just as the Soviet Union was emerging as a new threat to the United States. Greenland happened to lie along the most direct flight path to the Eastern United States from Russia.

“Greenland’s 800,000 square miles make it the world’s largest island and stationary aircraft carrier,” Time magazine wrote in January 1947. It “would be invaluable, in either conventional or push-button war, as an advance radar outpost, and a forward position for future rocket-launching sites.

The Americans had no intention of leaving.

The bad news was delivered in December 1946 by the U.S. secretary of state, James F. Byrnes. During a meeting at the Waldorf Astoria hotel in New York, Mr. Byrnes explained to his Danish counterpart, Gustav Rasmussen, that Greenland had become “vital to the defense of the United States.”

While the American military’s presence could be extended, Mr. Byrnes said, he had a better idea: Denmark should simply sell Greenland to America.

The idea “seemed to come as a shock” to Mr. Rasmussen, who accurately predicted that his government would reject the idea, according to another State Department memo. But unlike the current blowup, the matter was handled “quietly” by both sides, noted Heather Conley, a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute who specializes in the Arctic.

The Truman administration did not push, partly for fear that Moscow would claim that the United States had stolen land from a European ally. As the Soviet threat grew more vivid in Europe, Denmark became more willing to let American troops stay in Greenland.

Trump Administration: Live Updates

Updated

- The U.S. formally withdraws from the World Health Organization.

- A jet donated by Qatar could be deemed ready to serve as Air Force One by summer.

- House rejects measure to bar military force in Venezuela.

In 1951, the United States and Denmark reached an agreement “uniting their efforts for collective defense” under the auspices of the newly formed North Atlantic Treaty Organization. While stressing Denmark’s continued sovereignty over the island, the agreement granted the United States broad freedom to “construct, install, maintain and operate facilities and equipment” and to “station and house personnel,” along with other rights related to military activity. That included deepening harbors and even maintaining postal facilities.

The agreement did not include an expiration date, and Denmark has never asserted one.

One of the agreement’s few limitations was to delineate specific “defense areas” within which the United States could operate.

With the deal in hand, and freshly alarmed by a Soviet-backed communist offensive in Korea, the U.S. military quickly went to work. In a secret crash project, military engineers working around the clock in 24-hour Arctic daylight built a major air base at Thule in northwest Greenland. Manned by thousands of American personnel, the base’s 10,000-foot runway would serve as a launching point for strategic bombers and spy planes.

More than a dozen military bases and radar and weather monitoring stations eventually opened across the island. A 1,240-foot tower was erected at Thule for long wave transmissions to eastern Canada. In 1959, the U.S. started Project Ice Worm, another secret endeavor that envisioned a giant complex of bunkers, dozens of feet underground, meant to house nuclear missiles that could survive a Soviet first strike. (The project was deemed unfeasible and abandoned after several years.)

And as missile technology improved, the United States established more systems meant to provide early warning for a Soviet attack. While they were considered invaluable, the systems were far from foolproof: In October 1960, one U.S. radar system detected a massive Soviet missile launch with near certainty. It turned out that the system had spotted the moon rising over Norway.

Denmark raised few objections, satisfied that its sovereignty over Greenland remained protected. To underscore the point, a Danish flag flew alongside the American one at Thule.

The arrangement was tested in January 1968, when a U.S. B-52 bomber carrying four hydrogen bombs crashed while trying to make an emergency landing at Thule. The bomber had been part of an “airborne alert” program run by the U.S. Strategic Air Command, which kept several nuclear-armed bombers airborne 24 hours a day.

The bombs were incinerated on impact in conventional explosions, but left radioactive traces even after an arduous cleanup. Some Danish politicians expressed outrage that the United States had brought nuclear weapons to the island, although American officials insisted that such weapons were implicitly covered by the 1951 agreement.

At the peak of the United States’ military presence in Greenland during the Cold War, some 10,000 U.S. personnel were stationed on the island. But after the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the cost of a large footprint on an Arctic island made little sense.

Most U.S. installations on Greenland were closed over the next decade, with U.S. activity consolidating at Thule, whose name was changed in 2023 to Pituffik in an acknowledgment of a former Inuit settlement there. It is now a U.S. Space Force base, staffed by about 150 people who manage early warning radar and satellite communications.

Mr. Trump argues that Greenland is once again vital to American security, and many national security experts agree. They point to growing Arctic competition with Russia and China over natural resources and shipping lanes as melting ice reshapes the region. Mr. Trump also says that Greenland is crucial to the ambitious “Golden Dome” missile defense system he hopes to build in the coming years.

But Mr. Trump has never made clear why he must control Greenland to serve these needs.

Ms. Conley of the American Enterprise Institute said that a solution, if there were one, might mirror the events of the early Cold War. Having been denied ownership of the island, Mr. Trump appears to be considering an enhanced U.S. military presence on Greenland that is part of a new NATO mission to defend the island. “That’s the right approach,” she said.

Mr. Fried agreed, but said he wished the process could have played out quietly, the way it did nearly a century ago.

“Trump could have achieved this without all the drama,” he said.

Michael Crowley covers the State Department and U.S. foreign policy for The Times. He has reported from nearly three dozen countries and often travels with the secretary of state.

The post Nazis, Soviets and Trump: America’s Fixation With Greenland appeared first on New York Times.