There was nothing inherently alluring about the topic in artist Ben Shahn’s hands when, in 1940, he won a commission he called the “most important job that I could want.” It was the most Washington of subjects, a muse dressed in khakis and a button-up …

Shahn was painting Social Security.

At the time, the New Deal program was new, and Shahn, along with Philip Guston, Seymour Fogel and others, had been selected from 375 entries by the government’s prestigious Section of Fine Arts to paint the freshly minted Social Security Administration building in Washington, across Independence Avenue from the National Mall. He was proud to have the job of “putting a face on it,” according to a government history of the artwork.

Shahn lined the central corridor with dueling images of America, like a secular “The Last Judgment.” The east wall shows the ills Social Security aimed to fix: An elderly woman and child languish on crutches. Empty train tracks stretch before a jobless man and his child. Workers toil away in a gray, labyrinthine factory. The west wall, meanwhile, buzzes with motion — construction workers drill and hammer away at infrastructure that expands out of the frame; basketball players leap toward the sky.

The federally funded project would fill the Social Security building with more than 1,800 square feet of art, later inspiring a nickname among experts and enthusiasts: the “Sistine Chapel of the New Deal.”

But that lofty moniker belies a vulnerability that has come into focus during the second administration of President Donald Trump, which has listed the historic structure, now known as the Wilbur J. Cohen Building, for accelerated disposal.

Congress ordered the sale of the building last January through an amendment Sen. Joni Ernst (R-Iowa) added to a water act, but the designation from the General Services Administration, which oversees federal real estate, has heightened concerns. The process, which is not clearly defined, allows federal properties to be sold swiftly, raising fears among preservationists, historians and art lovers the government could sell the building with limited public input or review, a move that could lead to its demolition.

What would happen to the murals is an open question, as removing them may prove difficult, particularly for the Shahn and Fogel works, which are frescos painted directly onto the walls. Advocates for the building fear that without protections put in place ahead of a sale, the buyer would have no incentive to maintain the historical features inside. The building is currently closed to the public.

Asked about the sale, Marianne Copenhaver, a spokesperson for the GSA, said in a statement that the “GSA is executing a lawful congressional mandate and doing so in strict compliance with all federal disposition requirements, fine art protections, and every applicable law, rule, and regulation.”

The White House’s push to shed government buildings sparked concern early in Trump’s second term, when the GSA listed more than 400 properties for sale, shocking regional officials and real estate experts, and then quickly took it down. The GSA says it is now focusing on a shorter list, which includes the Cohen Building, to “drive maximum value for the federal real estate footprint.”

Sen. Ernst has described the building as a “ghost town,” but a portion of staffers from the U.S. Agency for Global Media and Voice of America still work in the building. Smaller offices of Health and Human Services Department are there, too.

In a statement to The Post, Ernst said “there should be no delay in taking this expensive waste monument off the taxpayers’ dime” and that “it speaks volumes” that more workers were not showing up to the office to see the murals. “Let the property’s buyer decide its artwork’s fate,” she said.

The building’s uncertain future has sparked calls for transparency and cast new light on its murals and the New Deal art programs that produced them.

To developers eyeing D.C.’s Southwest, the Cohen Building is an imposition on prime real estate. But to many who know its history, it’s a testament to the ideals of the New Deal era. As the Trump administration tries to slash arts fundingand shrink the social safety net, alive in the Cohen Building is a past when creativity was treated like a public utility. It’s a vision of a future where the public is sheltered from, in President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s words, “the misfortunes of life which cannot be wholly eliminated from the man-made world of ours.”

A bureaucratic edifice, a hidden trove

Designed by Charles Z. Klauder in “stripped classical” style with Egyptian Revival and art deco flourishes, the Cohen Building spans an entire block but fades into the beige bureaucratic rectangle that sits below the National Mall. Like Social Security itself, the building is so sprawling it’s taken for granted.

The building needed renovations for years, and before the current Trump administration the GSA had been working on a modernization feasibility study in hopes of bringing it to a rigorous energy-efficiency standard. Early estimates put the project at “north of a billion dollars,” said a former GSA employee, who spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation.

Although the building never became the headquarters of the Social Security Administration, advocates can’t help but compare its original purpose to its current state of disrepair and see a metaphor.

Much like the unassuming exterior of the Sistine Chapel, the humble facade of the Cohen Building disguises the art trove it holds. Reliefs by Emma Lou Davis and Henry Kreis crown entrances. The main corridor features the Shahn murals, and Fogel’s frescoes adorn one of the lobbies. Guston’s triptych graces the auditorium. A snowy landscape by Jenne and Ethel Magafan hangs in the boardroom. Taken together, it represents a cloistered collection of an endangered period of American art.

The Cohen Building was completed in 1940 and was soon turned over to the War Department, which operated the building as artists finished the murals.

In 2007, the Cohen Building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, but such a designation doesn’t exempt it from the wrecking ball. The listing simply requires officials to go through added processes, including a Section 106 review, before selling it. This might result in protective clauses or “mitigations,” such as photo documentation or public education on the building.

“It might sound kind of trivial, but sometimes there can be a lot” of mitigations “especially for a significant building downtown on the National Mall,” the former GSA employee said. The person is concerned about how Section 106 will be incorporated in an accelerated manner: “These things take a really long time for everybody to agree upon. And then sometimes they take a long time to execute.” The added time is meant to encourage preservation, the former staffer added.

In a petition, which has been signed by more than 7,000 people, Living New Deal requests to be a part of the Section 106 process. The group, which documents New Deal art around the country, also calls on the GSA and Congress to honor historic designations protecting the site and restore public access to the space, among other asks. Interest in the fate of the building’s artworks has grown since last year, when the New Republic and others began reporting on them.

It’s not clear whether the Trump administration is aware of the nature of the building’s art, but Mary Okin, assistant director of Living New Deal, finds the attempt to dispose of it fitting. “If you’re even remotely aware of what the building was all about and what the symbolism of that investment meant, then it’s a really great target for an agenda that opposes Social Security, social consciousness and inclusion,” she said.

An oft-forgotten movement

In the 1930s, Roosevelt’s New Deal reimagined the role of the state in American life, using extensive government programs, Social Security among them, to help the country recover from the Great Depression. The short-lived group the Artists Union pushed for relief for the cultural sector, and painter George Biddle, a classmate of Roosevelt’s, in an often-cited letter to the president, stressed that young American artists were eager to get involved in the “social revolution.” With government help, they could portray “the social ideals that you are struggling to achieve.”

This was certainly true of Shahn, who called Social Security “one of the real fruits of democracy.” His Cohen Building fresco was praised in a 1942 Washington Post article as “a necessary link in the interpretation of social conditions to the public.” The other Cohen Building artists had a similar ethos. Fogel, through work with Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, learned to create art that was “accessible to the masses by infusing the decorative with the didactic,” the Grace Museum says. Guston — now widely known for his paintings of hooded figures that aimed to, in art critic Aruna D’Souza’s words, “kneecap the Ku Klux Klan with humor” — once said, “The only reason to be an artist is to bear witness.”

Dorothea Lange’s iconic photograph “Migrant Mother” has become the poster child for New Deal art, but it only skims the surface. At the time, the U.S. government was the world’s largest patron of contemporary art. It paid 3,750 artists a monthly wage to create 15,000 artworks for government buildings. It sent photographers into the field to capture the lives of farmers, Lange’s famous subject among them. It filled post offices, hospitals, courthouses and other public spaces with murals.

According to John P. Murphy’s book on New Deal art, these federal programs generated 3,500 murals, more than 100,000 paintings and 17,000 sculptures, engaging 10,000 artists across the country.

Many blue-chip artists got their start in such programs, including Willem de Kooning, Jacob Lawrence, Alice Neel, Louise Nevelson, Jackson Pollock and others. “The project kept me alive and working. It was my education,” Guston said in a 1965 interview, adding that “practically all of the best painters of my generation developed on the projects.”

The New Deal art programs were so extensive, Murphy writes, that FDR supposedly believed that “one hundred years from now, my administration will be known for its art, not its relief.” Nearly a century later, that has not come to pass. “For all the stuff that the New Deal created — art, theater, literature, archives, museum collections — there is no New Deal art museum. There’s no scholarly society. There’s no scholarly journal. There’s nothing,” said Okin.

While many of the artists involved would have enduring success in the art world — Shahn and Guston have both had retrospectives at major museums in recent years — their New Deal works faded from memory.

“Things that are not market-driven in our society, that are about public service and public goods, just don’t receive the same kind of attention,” Okin said.

Art for — but not of — the government

Cultural institutions have long had space on their walls for political leaders and wealthy patrons, but in the Cohen Building murals, its ordinary American workers that star.

In his triptych “Reconstruction and the Wellbeing of the Family,” Guston shows a solemn-looking family sitting around a picnic table, eyes heavy, faces long. Images of laborers, knee-deep in work on a dam and at an industrial site, flank the figures on either side, almost as if the family is praying to them.

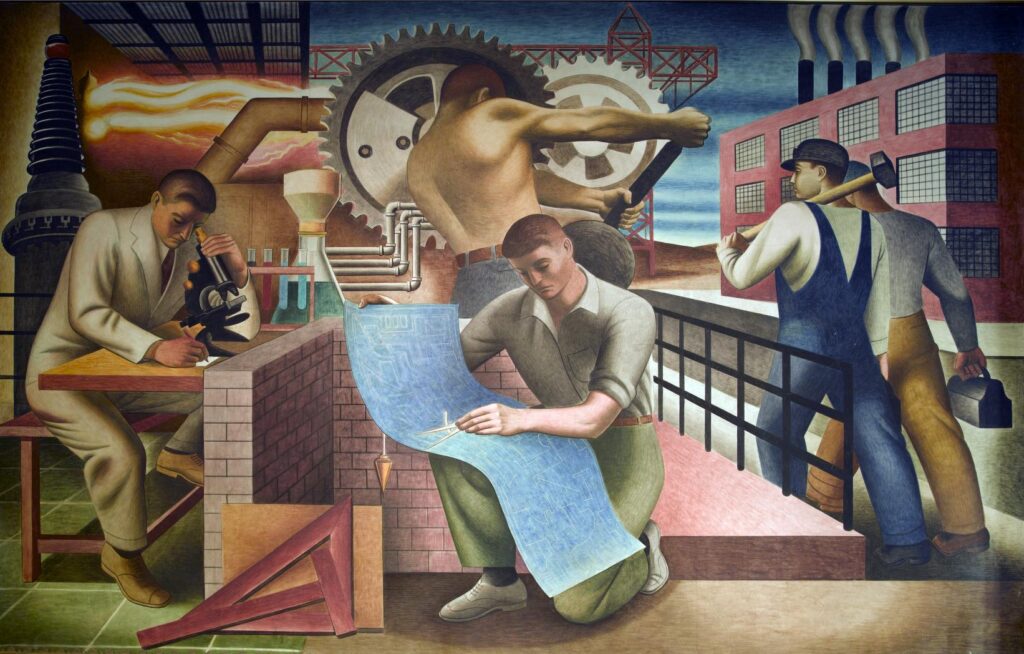

Fogel’s two frescoes in the lobby envision a kind of utopian future, built by workers and enjoyed through leisure. “Security of the People” features quiet recreational scenes: a girl drawing, a boy playing tennis. “Wealth of the Nation” offers a macho picture of industry and progress. A pair of men march off to work. A scientist peers into a microscope. A laborer pulls on a lever, arm muscles rippling.

The latter mural, which appears on the cover of Murphy’s book, distilled New Deal ambitions: “the dignity of labor, manual and mental labor working in concert,” Murphy said in an interview.

Such murals reflected a “very different conception of art in public spaces,” he said, pointing as examples to U.S. Capitol paintings that show, say, “the signing of the Declaration of Independence or George Washington enthroned on a cloud.”

“The idea that there would just be these anonymous workers who were meant to represent the basis of the wealth of the country was something that I think was really crucial to the program of the New Deal,” he said. Representing those workers could also stave off critics, who said New Deal programs amounted to handouts.

Indeed, the New Deal arts programs had their share of detractors, too. Conservatives thought the programs wasted money. Cultural elites resented the government for democratizing the stuff of high society. Eventually, even the artists themselves disavowed the work they made under the New Deal.

The Abstract Expressionist Arshile Gorky famously called New Deal art “poor art for poor people,” Murphy notes. “I think they found it a kind of embarrassing liability,” he said, attributing the attitude to “a kind of Cold War ideology, when abstraction was being upheld as the model of American creative freedom and intellectual autonomy.”

For some, New Deal art simply looked too much like Soviet socialist realism — that is, propaganda.

But Shahn “doesn’t overly glorify or overly idealize,” said Laura Katzman, an art history professor at James Madison University who recently curated a Shahn retrospective at the Jewish Museum in New York. His work is grouped with what’s called “social realism,” but she sees wider influences: Giorgio de Chirico’s moody surrealist paintings; echoes of Amedeo Modigliani’s distorted figures; a cubist treatment of space; Italian frescoes by the likes of Giotto.

While he was enthusiastic about Social Security, Shahn was no government parrot, Katzman stressed: “He understood that the Social Security Act had certain limitations and certain biases built into it.”

In the Cohen Building mural, Katzman points as examples to what appears to be a domestic worker and a group of farmers. Both represent parties that would have been excluded from Social Security in its early days. The subversive messages did not always slide through, though. When Shahn was pushed to remove a despondent-looking figure with an eye patch, he complied but then refused to remove the image of a child on crutches.

“Even within government art, he was trying to make sure that he could get his social message across,” Katzman said.

A message needs an audience, however, and if you try to stop by the Cohen Building to see Shahn’s murals, you won’t be able to get inside. Even though the public owns the murals (technically, they cannot even be sold), any hopeful visitor will probably find themselves peering at the Fogel murals from Independence Avenue. It’s a poignant place to stand these days.

Asked why the public should care about the art on the other side of those glass doors, Katzman put it simply: “Because it was made for them.”

The post The stunning art trove hidden in a D.C. building marked by Trump for disposal appeared first on Washington Post.