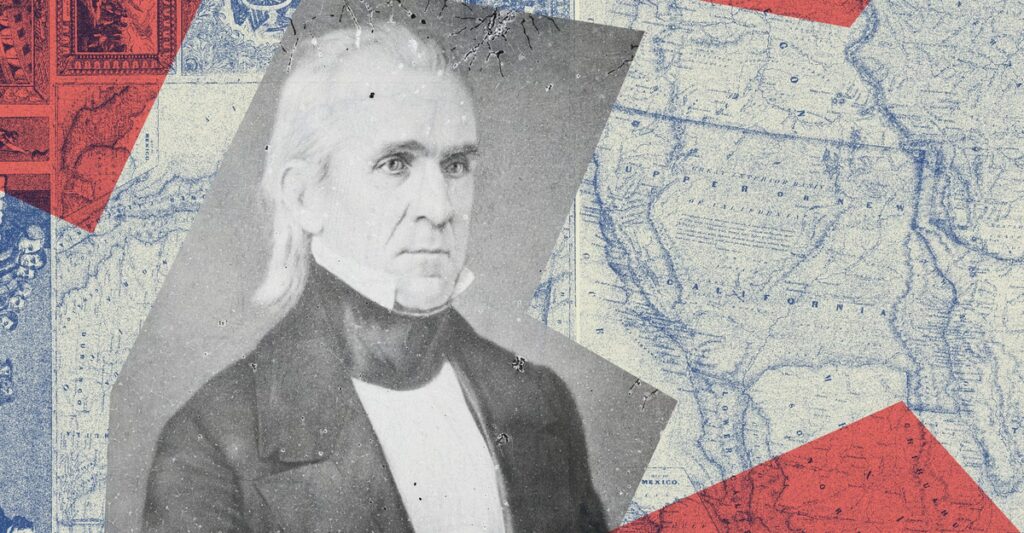

The notion that America would be stronger if it was bigger preoccupied several 19th-century U.S. presidents, but none more than James K. Polk. America’s 11th chief executive believed that expansion was America’s God-given right and duty. He argued that broadening America’s borders would deliver access to natural resources and enhance national security—and that no nation, not even an ally, should get in the way of that. Beginning with the annexation of Texas, which voted to become the 28th state in 1845, Polk aggressively expanded America’s footprint, enlarging the young nation more than any other president.

Polk sought to acquire Cuba, even if it meant the end of America’s alliance with Spain, pursuing an ambition that dated back to Thomas Jefferson. He preached the doctrine of “manifest destiny,” proclaiming that American settlers were divinely ordained to expand. He warned that if Cuba wasn’t annexed by the U.S., it would fall into British hands, leaving America vulnerable to attack. In May 1848, Polk offered Spain an astronomical $100 million (more than $4 billion today) to give up its claim to Cuba.

In a 21st-century revival of the same expansionist spirit, Donald Trump is fixated on annexing Greenland whether America’s Danish allies like it or not. Other presidents have invoked the legacies of George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, but for Trump, Polk is among the list of paragons. He has referred to Polk as a “real-estate guy” who got “a lot of land,” and he hung Polk’s portrait in the Oval Office last year, replacing one of Jefferson.

Trump has given many reasons for wanting Greenland—deterring China and Russia in the Arctic, enhancing U.S. national security, avenging his denial of a Nobel Peace Prize, seizing Greenland’s critical minerals, recognizing the huge island’s proximity to North America—but something much more basic and Polkian is at play. His advisers told me that the Greenland squeeze is part of a broader effort to cement his legacy among the elite club of presidents that includes Polk, Jefferson, and Dwight Eisenhower, who significantly expanded the size of the country. Trump, whose cartographical fascinations are well documented, wants his influence to be visible on maps for generations to come. Draping the world’s largest island in red, white, and blue is top of his list. On Tuesday, Trump shared an image of himself, alongside J. D. Vance and Secretary of State Marco Rubio, holding an American flag beside a sign that reads: Greenland—U.S. Territory Est. 2026.

Trump lowered the temperature slightly in a speech Wednesday at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, saying he would not use military force to seize Greenland but would “remember” if his goal were denied.

The most recent significant expansion of the United States came in 1959, when Eisenhower admitted Alaska and Hawaii as the 49th and 50th states. (The U.S. purchased Alaska from the Russian Empire in 1867 for $7.2 million, but it remained a territory for nearly 100 years; Hawaii was annexed in 1898, following a coup against Queen Liliʻuokalani and the Hawaiian Kingdom.) Trump recently proclaimed the “Donroe Doctrine,” his interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine, by which James Monroe aimed to check European colonial influence in the Western Hemisphere.

[Read: The fuck-around-and-find-out presidency]

In his second inaugural, Trump declared: “The United States will once again consider itself a growing nation, one that increases our wealth, expands our territory, builds our cities, raises our expectations, and carries our flag into new and beautiful horizons.”

Trump’s expansionism represents a clear break with the isolationist wing of his party—including some of Trump’s most ardent supporters—which believes that the way to make America great is to focus on what’s happening at home. If that was once how Trump saw it, that is no longer the case. “What better way to make America great than to expand America’s footprint?” one adviser told me. “He’s looking out for America’s interests. If it pisses other countries off, too bad.”

Polk was directly inspired by Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase a half century earlier, which added approximately 828,000 square miles purchased from France for $15 million. That acquisition doubled the size of the U.S., and the territory eventually formed all or part of 15 states. (Trump says he chose his envoy to Greenland, Louisiana Governor Jeff Landry, in part because of Landry’s understanding of the 1803 transaction.)

Polk vowed during his campaign to build on Jefferson’s success, much as Trump appears to be inspired by Polk. After the annexation of Texas, Polk set his sights on California, then a territory of Mexico known as Alta California, with deep-water harbors that he viewed as gateways for trade with the Far East. He also sought to limit British influence in North America, particularly in the Oregon Country, where he agreed to partition the land and end nearly three decades of joint occupation. By securing these lands, Polk argued, he was putting the U.S. on a path to dominance in the Pacific Northwest.

[Read: The hole in Trump’s rationale for acquiring Greenland]

Polk also attempted to buy California from Mexico for about $25 million. Mexico staunchly refused, leading Polk to launch the Mexican-American War. Most Americans backed territorial expansion, even though the war was condemned by some of Polk’s political opponents—including a young congressman named Abraham Lincoln—as an “unnecessarily and unconstitutionally commenced” land grab that empowered only slave-owning states and needlessly shed American blood on American soil. After the U.S. captured Mexico City in September 1847, some expansionists called for the annexation of the entire country. Opponents complained that annexing the whole of Mexico would be financially ruinous, and frowned upon having the military indefinitely deployed to Mexico, where most of the citizens would not welcome them.

Polk himself felt annexation of Mexico was a step too far. But he believed that California could be won at minimal cost. When the U.S. won the war in 1848, the government paid a final settlement of $15 million to Mexico for a swath of territory that includes present-day California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, and most of Arizona. (Around the same time as the peace treaty, gold was discovered in California, helping the U.S. government foot the bill.)

The expense of administering the newly acquired territory mounted as settlers began expecting more from the federal government. By the late 19th century, people began to see that annexing new territory was “stupidly expensive,” Amy Greenberg, the author of Manifest Destiny and American Territorial Expansion, told me. She said people at the time began saying, “We don’t need the expense. We don’t need to pay for an army to go somewhere and occupy it. We don’t need to try and administer a bunch of people that hate us. All we need to do is put commercial pressure on them, make treaties that are in our favor, and then economically exploit these people.” That principle broadly prevailed in U.S. debates over expansionism. Now Trump is turning back the clock to a mid-19th-century view of the world and America’s place in it.

Trump went hard this past weekend on his rhetoric of acquisition. Stunned European officials reinforced their military presence on Greenland this month and denounced the threat of aggression by a NATO member.

On Saturday, Trump vowed to implement a wave of tariffs—rising to 25 percent by June—on several European nations until a deal for Greenland is reached. (Spain, Polk’s colonial nemesis, is not among the targeted nations, although its prime minister warned last week that annexing Greenland would be a “death knell for NATO.”) Trump also has vowed to “take back” the Panama Canal, falsely asserting that China is operating it.

And Trump has repeatedly referred to Canada as the 51st state, a prospect that former Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said had “not a snowball’s chance in hell” of happening. At least one adviser has told me they’ve heard Trump refer to Venezuela as the 51st state as well; Trump announced that the U.S. would “run” Venezuela following the capture and arrest of its president early this month. Trump has also suggested annexing Mexico to resolve trade imbalances. “If we’re going to subsidize them, let them become a state,” he said in 2024.

“The media doesn’t know the difference between what’s real and what’s tongue in cheek,” another Trump adviser told me, distinguishing between Trump’s ambition to annex Greenland for national-security reasons (real), and his interest in annexing Canada (joke). But as part of the team that first reportedTrump’s interest in buying Greenland back in 2019, I can confidently say that many of his advisers believed, back then, that his musings were in jest. He had enlisted the White House counsel’s office to look into its feasibility at the time, but few of the people I spoke with thought much would come of it.

Flash forward almost seven years, and Americans are considering whether the president, now back in office, will invade a NATO ally. Trump’s belligerence is stoking controversy, even in his own party. I spoke with two Republican members of Congress who told me that although they support Trump’s interest in expanding American influence in the Arctic, they are not ready to go to war for Greenland. Most Americans feel the same. A CNN pollthis month found that 75 percent of Americans oppose attempting to take control of Greenland. (Even Republicans are split down the middle; half of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents are in support, and half are opposed.)

In 1867, the then–secretary of state launched an inquiry into buying the territory, along with Iceland. In 1946, President Harry Truman offered to buy Greenland from Denmark for $100 million. Denmark refused to sell. The American Action Forum, a conservative think tank, looked at these values as percentages of GDP growth, and—accounting for enormous GDP growth since those offers were made—estimates that acquiring the island today would cost $12.9 billion to $19.6 billion. “These bids would end up providing Denmark between three and five times the total GDP of the island,” AAF said in a 2025 report.

In Davos on Wednesday, Trump described America’s current relationship with Greenland as a “lease,” adding, “Who the hell wants to defend a license agreement or a lease?”

He also appeared to confuse Greenland with Iceland in his speech: “Our stock market took the first dip yesterday because of Iceland, so Iceland has already cost us a lot of money.”

[Read: Trump exhaustion syndrome]

The previous U.S. offers were contingent on Denmark’s agreement to part ways with the island. Ahead of the World Economic Forum, Trump suggested a readiness to seize the territory however he has to, threatening the survival of NATO in the process. “We are all urging the White House to bring down the temperature,” one Republican lawmaker told me.

On X, Republican Senator Thom Tillis of North Carolina criticized the push for “coercive action” against Greenland as “beyond stupid” and harmful to American businesses and allies. He issued a statement with Democratic colleagues emphasizing that Greenland is “not for sale,” and that its autonomy must be respected. But Tillis fell short of saying he would vote to impeach the president if Trump followed through with his threats.

Even Trump’s critics acknowledge that Greenland is crucial to protecting U.S. interests in the Arctic, just as Polk and Jefferson before him argued that Cuba was crucial for protecting American interests in the Caribbean. (About a century later, the potency of that threat became clear when the Soviet Union deployed nuclear missiles, sparking the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962.) But the point of NATO is to provide collective security, which should mean U.S. interests in the Arctic are already covered by Denmark. “What he’s ignoring is that NATO already supposedly protects Greenland from Russia and other countries,” Paul Frymer, a Princeton politics professor, told me.

Polk’s offer to buy Cuba from Spain was meant to remain quiet as he sought to secure a deal, but the news leaked to The New York Herald. Spain refused the offer and was deeply offended by its ally’s behavior; Madrid declared it would rather see Cuba “sunk into the ocean” than transferred to a foreign power.

There was also resistance within the U.S., a preview of the divisions that would ultimately lead to the Civil War more than a decade later. “The South wanted Cuba, and the North didn’t,” because the South saw the possibility of adding to the ranks of slave states and the North was opposed, Frymer told me. Polk backed down, unwilling to flout the law or the role of Congress in his pursuit (two things that Trump, so far, has ignored in his grab for Greenland and his recent military action in Venezuela).

“There was an acknowledgement of international law when it came to starting a war with a major European power,” Greenberg, who is also the head of Penn State’s history department, told me. “The idea that the United States would say Hey, we want what you have, and we need it, and if you won’t give it to us we’re gonna go to war against you’ was seen as not acceptable.”

Polk’s Cuba failure fueled resistance to expansionism in the following decades. After the Civil War, Ulysses S. Grant sought to negotiate a treaty to annex the self-governed Dominican Republic, then known as Santo Domingo, which he viewed as a component of Reconstruction and a strategic option for stationing the U.S. Navy. But Congress shot it down, telling him the country was big enough.

The post Trump’s Role Model for Seizing Greenland appeared first on The Atlantic.