It was a real pyramid scheme.

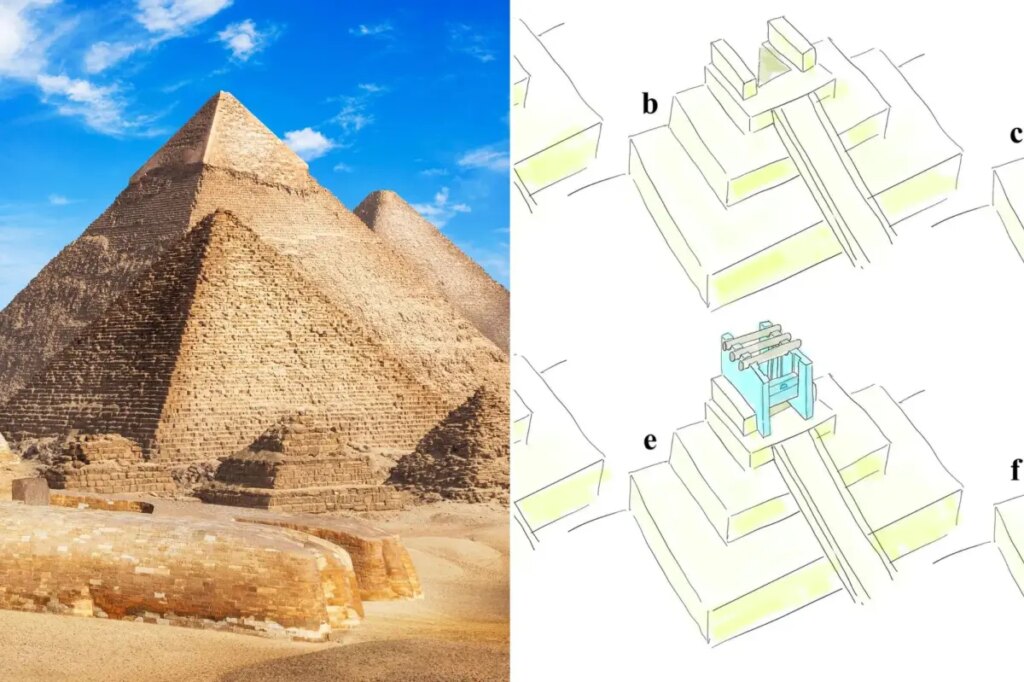

Scientists have proposed a groundbreaking new theory on how Egypt’s Great Pyramid was built, positing that they used a pulley and counterweight system to erect it so quickly. The radical research was published in the journal Nature.

“The construction proposal based on analysis of the pyramid’s architecture and masonry is physically advantageous and can explain the fast construction,” writes study author Dr. Simon Andreas Scheuring of Weill Cornell Medicine in New York.

For decades, archaeologists have racked their brains over the construction of Egypt’s largest pyramid, which is comprised of 2.3 million limestone blocks, the smallest of which weigh two tons, while the largest tip the scales at over 60.

According to the team’s calculations, the impressive structure was erected over two decades, meaning that a brick got laid every minute, per the study.

Prior scholarship states that the builders completed this monumental feat of building by employing “construction-ramps and a layer-by-layer bottom-to-top growth progress.”

However, the study authors claim this rudimentary technique wouldn’t have allowed them to hoist and install hefty blocks at the aforementioned breakneck pace.

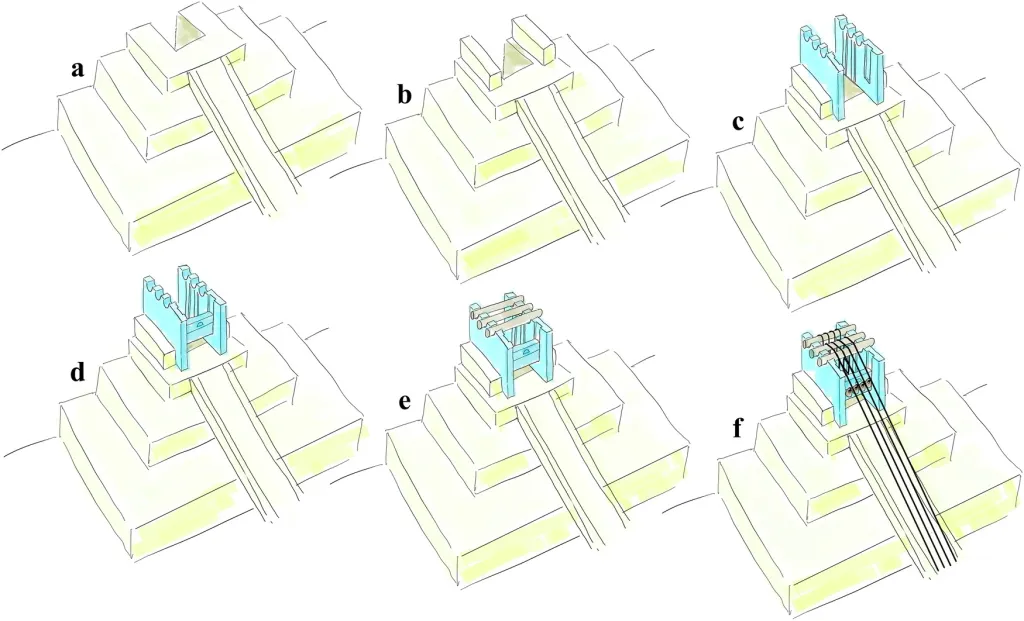

Scheuring and crew calculated that they could only achieve this architectural feat with “pulley-like systems fueled by sliding counterweights down sliding-ramps.” These would’ve provided the power and precision necessary to lift these hulking blocks to the upper levels of the Great Pyramid.

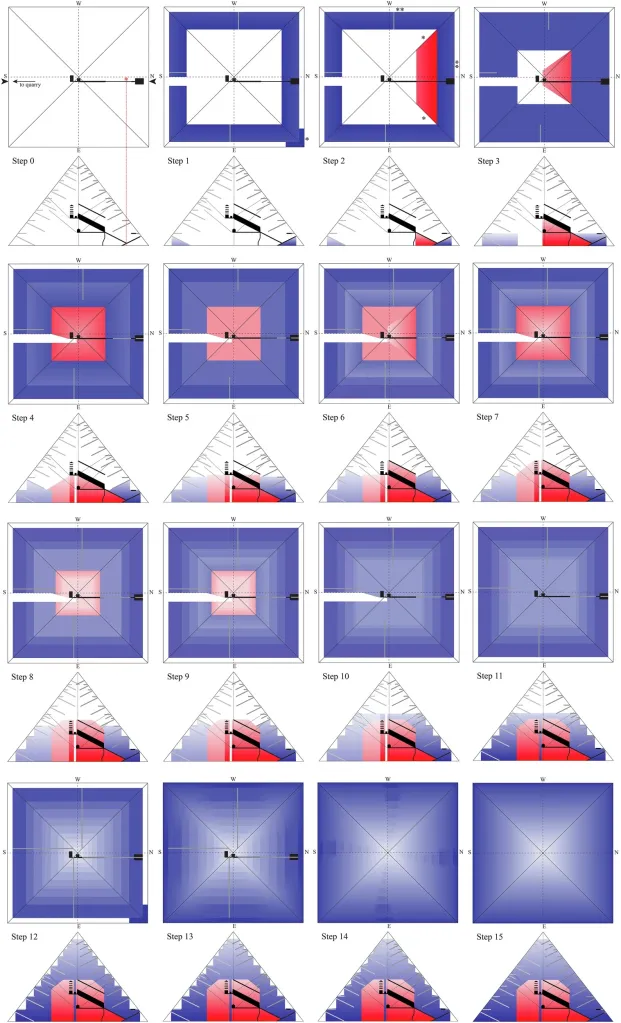

If true, this would mean that the architectural marvel was built from the inside out, beginning at the core and using a pulley system as the pyramid progressed.

They based this bold assertion on several architectural features inside the iconic prism, reinterpreting the Grand Gallery and Ascending Passage as sloped internal passages that served as ramps for the counterweights powering the pulley system.

Of particular interest were the wear and tear and polished surfaces along the walls of the Grand Gallery, which they believed provided evidence of sliding sledges and not food traffic.

They also had a new theory regarding the Antechamber, the small granite room that archaeologists have long believed to house a security grate used to deter tomb raiders.

Scheuring told Artnet that “the Antechamber’s assignment as a portcullis system (vertical sliding grate) is questionable because it is non-functional.” He found it difficult to fathom that they’d purposefully botch its design when everything else was so precise and purposeful.

According to the study, this chamber was actually a fulcrum in the pulley system where laborers would hoist the most cumbersome construction components.

This pulley system featured numerous gears, allowing them to adjust to increase lifting power, akin to shifting gears on a bike.

In general, Scheuring found it interesting that the major passages and chambers are situated off-center rather than symmetrical, as was standard with structures that were built from the ground up.

He theorized that this off-kilter layout was due to the fact that the laborers had to build around the mechanical constraints imposed by the pulley systems.

This would also explain some of the theories’ more baffling anomalies, notably the Pyramid’s convex faces and how the blocks get smaller toward the summit.

Scheuring postulated that they shed light on “the physics of how the blocks were lifted,” specifically how the lifting points shifted as the pyramid grew and how the stones became lighter the closer they got to the peak.

The post Scientists propose bold new theory on how Egypt’s Great Pyramid was really built appeared first on New York Post.