Georges Borchardt, a literary agent who arranged for the publication in English of Elie Wiesel’s searing Holocaust memoir “Night” after it was rejected by 14 American publishers, and who introduced American readers to masters of the avant-garde like the playwright Samuel Beckett, died on Sunday at his home in Manhattan. He was 97.

His daughter, Valerie Borchardt, confirmed the death.

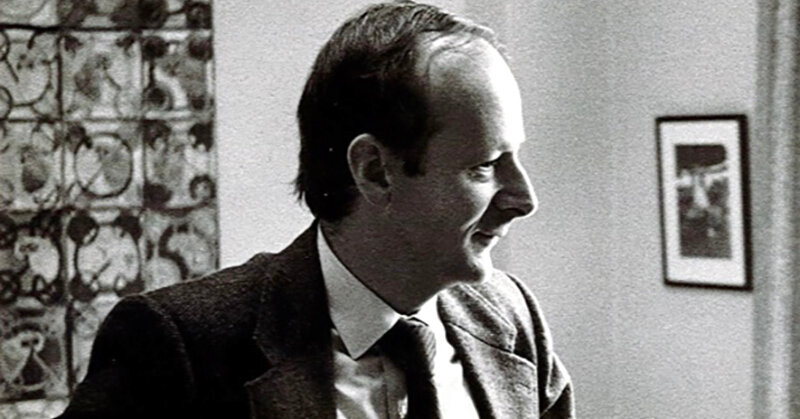

Mr. Borchardt, an urbane and debonair man whose wry observations came with a slight French accent — a remnant of his upbringing in Paris — had an astute eye for literary talent. At various times, he or the Manhattan agency that he and his wife, Anne Borchardt, founded in 1967, Georges Borchardt Inc., represented five Nobel laureates, eight Pulitzer Prize-winners and one statesman, the French president Charles de Gaulle.

The agency’s roster of authors included a constellation of acclaimed novelists and nonfiction writers, including Ian McEwan, T.C. Boyle, Tracy Kidder, Mavis Gallant and Anne Applebaum and the estates of Tennessee Williams, Aldous Huxley and Hannah Arendt.

It also introduced to American readers major works by French writers like Roland Barthes, Marguerite Duras, Michel Foucault, Alain Robbe-Grillet and Jean-Paul Sartre as well as the French West Indian author Frantz Fanon and the French-Romanian playwright Eugene Ionesco.

“I don’t ask writers to pass some kind of test,” Mr. Borchardt told The Paris Review in 2018, explaining how he chose his clients. “It’s really all instinct. You can sometimes see it in the page or in the person. If it’s on the page, it’s the actual writing. The way things are expressed differently.

“To most people,” he continued, “there’s only one way of saying something: ‘The vase is over there.’ So what can you add? But in fact there are millions of ways of saying it, sometimes without even mentioning the vase.”

Mr. Borchardt drifted into the literary profession almost by happenstance.

He arrived in New York in 1947 as a 19-year-old orphaned survivor of the genocide of Europe’s Jews and placed a classified ad seeking an unspecified job. He received a response from Marion Saunders, who ran a literary agency that specialized in foreign writers. She was apparently drawn to the fact that he spoke French.

Ms. Saunders hired him for an entry-level job that entailed bookkeeping and fetching coffee. In his spare time, he was asked to peruse some of the French submissions. Within a few years, he was sounding out editors at publishing houses, asking if they’d be interested in buying manuscripts he liked.

One of the first works he negotiated on his own was an enigmatic but tender and often darkly funny French play written by a lanky Irishman, “Waiting for Godot.”

Mr. Beckett in 1953 was already in his late 40s and barely known outside of Europe. “From an American point of view, he was over the hill and didn’t hold much promise,” Mr. Borchardt recalled to The Paris Review.

Grove Press offered Mr. Beckett $1,000 for the play and two novels, all of which he had to translate into English himself. Over time, critics came to regard “Waiting for Godot,” an absurdist tragicomedy about two tramps waiting for an elusive visitor, as one of the masterpieces of 20th century theater; Mr. Beckett won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1969.

A few years after helping to find an American publisher for Mr. Beckett, Mr. Borchardt, whose mother had been killed at Auschwitz, said he was profoundly stirred by “La Nuit,” a short, French-language memoir by a freelance journalist, Mr. Wiesel, recounting in harrowing detail his experience as a teenager in Auschwitz and Buchenwald.

Mr. Borchardt sent an impassioned pitch to 14 mainstream publishers, praising the book as one “that I feel more strongly about than any other I ever sent you.” All turned it down as too bleak, morbid or of minimal interest to their readers just a decade after the war had ended. A Knopf representative, he recalled, rejected it by saying, “‘I imagine you will have someone in your office who may want to deal with it abroad in England, or wherever.’ Wherever!”

Finally, in 1959, the small publishing house of Hill & Wang offered $250 for the manuscript, whose French title was translated into English as “Night.” The book initially sold about 1,000 copies, but sales surged after the 1961 trial in Jerusalem of Adolf Eichmann, an administrator of the so-called Final Solution, and Israel’s victory against its Arab neighbors in the Six-Day War of 1967.

In time, thousands of schools made “Night” required reading, and an endorsement by the popular daytime television host Oprah Winfrey in 2006, on the “book club” segment of her show, propelled it onto best-seller lists. By 2020, its worldwide sales were estimated at 14 million.

“I really feel in many cases that I’ve made it possible for a book to succeed and also made it possible for a writer to go on writing,” Mr. Borchardt said in The Paris Review interview.

In 2010, he received France’s highest award, the Legion of Honor.

Thomas Georges Borchardt was born in Berlin on Feb. 24, 1928, the youngest of three children of Bruno and Anne (Herzberg) Borchardt. His parents moved the family to Paris after Hitler came to power in 1933. His father became head of the Polydor record company, whose artists included the singer Edith Piaf.

The family lived in the moneyed 16th arrondissement, and his mother ran the household with a maid and a cook. Young Georges was an avid reader, devouring translations of “Ivanhoe” and the novels of James Fenimore Cooper. But his relatively tranquil life changed dramatically with the German invasion of France in 1940, after which he was forced by Nazi occupiers to wear a yellow star, to identify him as Jewish.

In 1942, tipped off by a family friend, he, his mother and two older sisters, Marguerite and Ingrid, escaped a roundup that sent 13,000 Jews to the Vélodrome d’Hiver arena before their deportation to Auschwitz. His father had died of cancer a few months before the German assault.

The family made its way south to Nice, which was in a demilitarized zone and later under the control of Germany’s ally, Italy.

With the help of a faculty professor, Georges attended a lycée in Aix-en-Provence “without being officially on the books,” he later said, while his sisters hid in a village near Nice. His mother was eventually arrested by members of the antisemitic French militia and deported to Auschwitz.

After the war, he and Marguerite repossessed the family’s Paris apartment, and he began law school, though he soon found he hated it and went to work for Polydor. His sisters had worked at an American field hospital and decided to emigrate to the United States; Georges joined them.

In addition to his daughter, who is the foreign rights director at her parents’ agency, he is survived by his wife, Anne Bolton Borchardt, whom he married in 1961; and two granddaughters.

Mr. Borchardt’s early career with Ms. Saunders was interrupted by service in the U.S. Army during the Korean War. While assigned to an intelligence unit based in Iceland, he used two leaves to travel to Paris and establish connections among publishers there.

After his return to New York, he used the G.I. Bill to take night classes at New York University. He received a bachelor’s degree in English in 1953 and a master’s in romance languages in 1956.

Mr. Borchardt was still working as a literary agent, at his East 57th Street offices, at the age of 92. What he prized in a writer, he said at the time, was a “sense of style and language.”

He added that he had certain stipulations before championing a manuscript. “For nonfiction,” he said, “a subject I am interested in and the conviction that the writer is tops in his field. For fiction, I want to fall in love.”

In 2009, he spoke to the magazine Poets & Writers about what he found most rewarding about his work as an agent.

“It’s when you can bring good news to one of your authors,” he said. “Their book just went into a fifth printing. We found a home for that short story that we both liked but so-and-so didn’t want. Or we just sold, say, Catalan rights to their book. Or Basque rights. I didn’t even know there was such a thing! I knew there was a Basque dialect, but I didn’t know that people actually read in Basque. To be able to make those phone calls gives one so much pleasure.”

Ash Wu contributed reporting.

The post Georges Borchardt, 97, Dies; Literary Agent Championed Wiesel’s ‘Night’ appeared first on New York Times.